You know those moments where your mental rolodex starts spinning, desperately searching for a card catalog entry for a useful text or quote, read years ago, that might help make sense of an upsetting experience in real time? This happened to me last month, in one particularly grim gallery of the extremely disturbing twelfth edition of the Berlin Biennale.

I stood paralyzed in front of two side-by-side displays at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art. To my right, a group of people sat silently staring at a screen, chins resting on furtive fists, watching looped grainy surveillance footage of detained asylum seekers at the US/Mexico border. The refugees in the video shivered and huddled together, slowly inching around a freezing cell, trying to keep warm under thin silver space blankets—dehumanized and reduced to a visual uncomfortably evocative of old black-and-white documentation of Warhol’s “Silver Clouds.” To my left were the daunting blocks of didactic text and archival images I had just diligently read, outlining the mass rape of German women by allied soldiers in the ruins of postwar Berlin in the weeks following the city’s “liberation”.

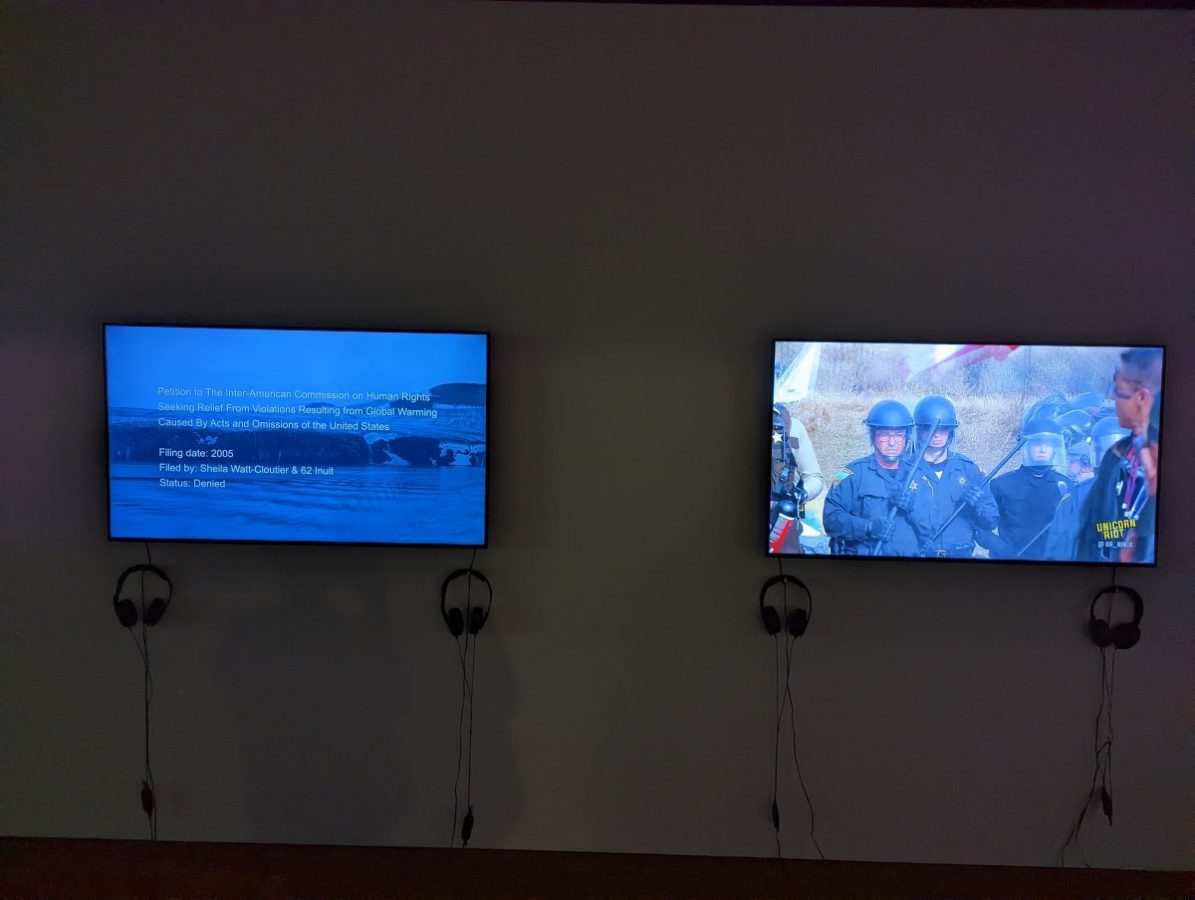

The two pieces, “Icebox Detention Along the US-Mexico Border” (2021-2022) by Susan Schuppli and “The Natural History of Rape” (2017/2022) by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, presented violence by agents of the state with as cold and clinical a lens as their titles would suggest. Having just paid an admission fee to become a spectator of human suffering, packaged dispassionately, I found myself wondering, “Why am I doing this to myself?”

Psychically scrolling through the hazy copies-of-copies of the untold pages of critical theory PDFs our mental libraries end up stuffed with after grad school, I tried to recall some pearl of wisdom from the writer Maggie Nelson. I remembered appreciating her book The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning, which interrogated artists’ impulses to present violence as a curative remedy for the viewer’s apathy—as if we had all been born with an original sin, empathy out of alignment, and the artist’s role were to forcefully jolt it back into place with an “orthopedic” shove.

In the weeks that followed, I casually revisited the text a few times, hoping to find some brilliant quote to summarize my complicated feelings about how to critique an art Biennale so loaded with representations of nonfictional cruelty that it included a literal rape museum. And I came up empty-handed, partly because Nelson’s conclusion is largely that sometimes ambivalence is okay. And then I remembered that was the lesson I had originally cherished back in grad school—one that probably informed my art-viewing career more than any other.

The problem is, I really wanted to enjoy the Berlin Biennale.