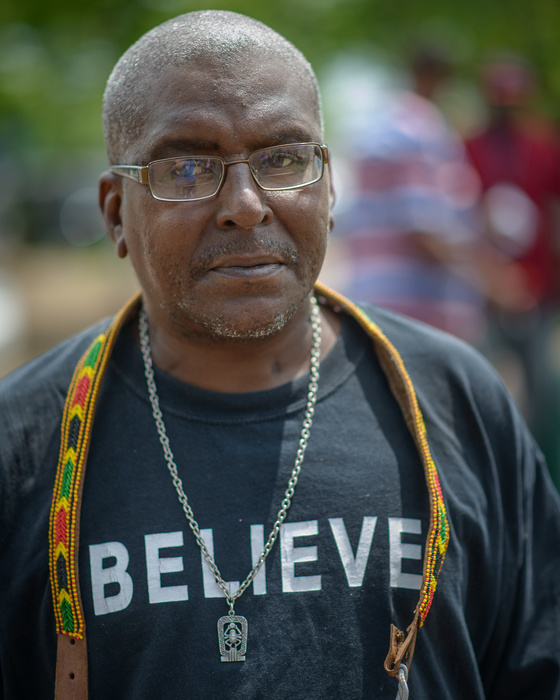

An Interview with Dwayne Butcher

Nate Larson is an artist living and working in Baltimore, MD. He works with photographic media, artist books and digital video. Most of his current artwork, research, and collaboration explores the linkage between human experience and the site on which it happened through technological, cultural, and historical threads. He is currently on faculty in the Photo Department at the Maryland Institute College of Art and chaired the 2014 national conference of the Society for Photographic Education.

On the morning of April 28th, Larson, accompanied by his students, went to Penn and North Ave. to document the events firsthand that were playing out in the national media. That series, All Night, All Day went viral soon afterwards. He took time out of his busy schedule to answers some questions about that experience, Walmart, and his legendary contact list. Here is part of that exchange.

Dwayne Butcher: What were your immediate thoughts when you first were at Penn and North? What kind of images did you think you would get? What were you looking for?

Nate Larson: For me, it was really about seeing for myself. I watched the television coverage of the night before and kept seeing the same few video clips of cars burning. I was deeply suspicious of the media narrative and felt that there had to be more that we weren’t seeing.

DB: Were you surprised by the response to the series All Night, All Day from the public, especially the media? Did the other outlets that choose to publish your work contact you first?

NL: I made pictures that I thought were important based on events that were happening in my city. I didn’t have any plan to get them out there – they were just important to me personally to make. I edited them and posted them to my own website the same days that I took them, which is way more quickly than my usual working methods. I don’t consider myself a journalist and I don’t usually work on that sort of fast-pace deadline. I do think of myself as a documentarian, though, which to me implies a longer commitment to a subject.

I then posted the links through social media channels and was amazed at how viral it became – one post was shared over 750 times through my FB page, and then when I started clicking through the shares, many of them were re-shared hundreds of times. I didn’t anticipate that level of engagement; I was just putting out images that I felt were important to see and to share what was happening in my city. I think that social media users responded to that level of personal engagement and the images also offered a differing point of view than the mainstream media.

The media attention followed the social media attention. The first were y’all – BmoreArt – based on my relationship with Cara Ober. She saw the images on my FB post and immediately wrote wanting to publish. The second was the CNN piece, which came off Twitter when a curator that I’m working with on other projects retweeted my images to the CNN photo editor directly (my understanding is that they’re friends already). The third was Hyperallergic, which I think came from Cara sharing the work with them. I was already on their radar, as they had previously written about both my solo and collaborative work, so I’m sure that helped as well. Medium’s Vantage was next, which I’ve had a relationship with that editor for a while and he saw it on my Twitter. He has a strong interest in social justice issues, so it wasn’t a surprise that he responded to the work.

Frieze was next, my MICA colleague Ian Bourland writes for them and asked if my images could accompany his written piece. Ian and his wife Barbara were out with our class while we were photographing so it felt good that we had shared that experience. Buzzfeed News picked it up off Twitter, which led to the Boston Globe seeing it there and writing a followup story. And I was also interviewed on Delaware Public Radio because I was previously scheduled to moderate a symposium at the Delaware Center for Contemporary Art and they wanted to talk both about the symposium and the new photographs. There were also several other media outlets that got in touch based on Twitter but didn’t ultimately end up running the images, so it was interesting to see how media inquiries came in and then which ones went forward.

I ended up having mixed feelings about the media attention – I felt like my images were different than the main media narrative, so on one level, I was happy that the photographs were representing a different narrative to a wide audience. On the other hand, I worried that some of the nuance of the images was lost, and most of the headlines (which I have no control over) reinforced the binary nature of the conflict that was painted by the media. I don’t think that the conflict was binary and it’s an incredibly complex set of circumstances. A lot is lost in the media constructed soundbites and the short attention spans of the average American media viewer.

DB: We all know the varying opinions of the root cause of what actually took place recently in Baltimore. The medias perception versus reality and all the insane and bizarre comments made on social media. Did you experience any of that with these images?

NL: The vast majority of the comments on my work were very positive and that was a pleasant surprise. It was also amazing to see that people responded strongly enough to my images to share and re-share. I never anticipated the viral aspect.

There were a few individual responses that surprised me, like when MICA posted a link to the CNN article on their FB page and someone (that I don’t know) responded “bs. I know there are black police officers because i went to MICA. where are the pictures of the black police officers?” I didn’t know quite what to do with that, but I chimed in that those were the particular officers at that particular place and time. I felt like there was a bigger conversation to be had there about Institutional Racism that goes beyond the race of the officers involved, but it’s hard to have meaningful conversations with strangers on social media.

I received a tough critique from an artistic colleague about “Holding That Line, Part Two” She felt that by photographing with shallow depth of field that it objectified the people and held them up as “the good ones” and by implication made all the other protestors “the bad ones.” I could see the basis for her reading but my intent was certainly not that. Her reading was reinforced, though, by a right-wing viral photograph of the line of citizens (not one my photographs) that added the caption “These are the citizens of Baltimore lining up to protect police. Make them famous!” That plays easily in a social media echo chamber but the fundamental problem is that it’s false. From talking to the citizens, they were not there for the police, they were there to protect their fellow citizens from provoking a police response that would be hurtful and destructive to the community members. The spin machine is destructive and disheartening and I hope that my images disrupt, rather than contribute, to it. The tricky thing about photography is that the same image can be used for different purposes.

The other thing that concerned me was when too much attention was focused on me (as the photographer) rather than the issues at hand. My hope was always to use the photographs to direct the conversation towards the larger issues and systemic problems in our city.

DB: Did you have a conversation with your class about going to shoot the events? Was there any talk about possible danger or what to expect, what to avoid?

NL: The class is “Contemporary Directions in Photography,” which is an upper level seminar class in which we survey and discuss contemporary photographic practice. When I came to class the morning of April 28th, I told the students that I didn’t know how to carry on as usual and that I couldn’t pretend that nothing was different in our city. We had other topics on the class schedule, but it felt important to talk about the current events and to talk about what had happened in our city. We had a short conversation about the events and the media coverage that we had seen the night before. I posed an open question about seeing for ourselves and we decided as a group to retrieve our cameras and to go bear witness. It was a smaller group of 6 students and a grad TA, so it was a little easier to be agile than if it were a larger group. We agreed to stick together and to keep an eye on everyone and I gave my cell phone number to everyone, just in case. Going out to photograph and just being in the community felt like the right thing in the moment. It wasn’t easy but it was necessary.

It was very spontaneous, so none of us had time to overthink it. When we came back, I told my chair about it, just in case of any pushback. She was immediately supportive, as were all the other MICA administrators that I spoke with, including the Vice-Provost of Undergraduate Studies. The Office of Communications also posted the resulting news articles and wrote an article about us. I felt very fortunate in this risk-adverse contemporary culture to be supported by my institution in doing important work like this with students.

DB: After going through something like this, making the work, having the response that it did, what do you do now? Does it change anything in your thinking about your other work or projects?

NL: Yes, I think that it has fundamentally transformed something in me. But given that I started photographing only three weeks ago today, it’s hard to know exactly what has shifted. I hope that the audience will stick with me beyond the news cycle.

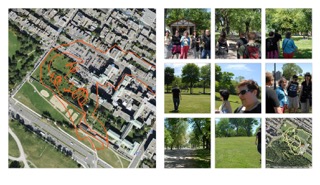

One of my concerns in photographing is the fear of parachuting in and I’m looking to build long-term relationships with the communities involved. I’ve started reaching out to community groups and am currently talking with Jubilee Arts, which provides arts classes to the residents of the Sandtown-Winchester, Upton, and surrounding neighborhoods. The director invited me to photograph their block party last week and I posted a set of photographs online here: http://www.natelarson.com/block-party.

I’m hoping that this will be the start of a long-term engagement.

DB: You collaborate frequently with Marni Shindelman. How did this collaboration first come about? How does this work differ, or not, from your solo practice?

NL: We met a long time back – I think 2003 – after I saw her give a presentation at a conference. She was making work based on internet urban legends, like the husband who was allergic to cleaning chemicals and his wife who used this intimate knowledge to poison him. I was making work about religious miracles, many of which were sourced from the internet, so there was a natural affinity between our practices. We didn’t really connect at that moment, there was some missed mail art that was sent and not received, but then we met again a number of years later – around 2006 – and became fast friends. In March 2007, we were hanging out at a conference and the question of “what would it look like if we made something together?” came up. We sent some mail art back and forth after that, and then I did a residency at Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester that summer, where Marni lived at the time. We started making things together that summer and now we’re still going strong eight years later.

DB: With Marni in Athens, GA and you in Baltimore, MD, how do you and how often can you work together?

NL: Distance has been a challenge, especially since we have never lived in the same place, but we make the most of online tools. Just the other day, we had a video chat going on our phones while editing a shared Google doc on our laptops. The work is frequently about the ideas of technology and distance, so in a way, our working methods informs the work.

There have been plenty of inconvenient moments, like having to overnight a box of prints from me for her to do a studio visit with a curator, but it’s all pretty minor nuisances. We have learned each others rhythms pretty well at this point in our collaboration, so we try to anticipate as much as possible and are flexible when we have to adapt.

Most of our new shooting and production time comes through doing residencies or site-specific projects together, which mostly take place during the summers and winter breaks. The rest of the year is refinement, developing the material, and researching future work.

DB: How do you decide which idea will work best on your own or as a part of the collaboration? Has there ever been a time when you begin a series on your own and decided it would work best as collaboration or vice versa?

NL: Our collaboration comes out of our conversations, which is pretty specific to our process. It usually includes collecting a wide array of intriguing news articles or other clippings from the internet, and then distilling it down and perpetually refining. At residencies, we usually have a large wall covered in clippings, with notes everywhere and arrows connecting ideas. It’s a pretty fluid process but it’s very exciting when both of our brains are clicking away. Marni always says that collaboration is like whispering your vulnerable little thoughts in someone else’s ear and having great things grow out of the affirmation.

Our practice has always developed pretty naturally, with one idea leading to the next. I don’t know that I’ve ever felt territorial about sharing an idea in the collaboration; if it gets shared and has dual traction, we run with it. If it doesn’t, it gets filed away, and perhaps we’ll come back to it.

We’ve also learned over time the kinds of topics that we’re interested in, so for example, most of our work together has to do with contemporary culture as manifested through technology and relationships. A lot of my individual work references American history, but that’s not something that means something to her in the same way, so it frees me up to work independently. And a lot of her work is driven by relationships with animals, which is not something that fits into my practice. Carving out these individual spaces is also important to the collaboration in that it gives us freedom and also makes our collaborative time richer.

DB: You recently had an exhibition open at Crystal Bridges showing some of your collaborative work. How was that experience and how is that museum? Did it seem out of place? Were locals a part and active with the programming?

NL: Crystal Bridges was great – it was really wonderful to be featured in the museum and they acquired the eight pieces that they exhibited. In curating the exhibition, they did 1,000 studio visits with artists and then selected 100 artists/collaboratives for the exhibition. We were honored to be chosen and the curator and museum staff were all very supportive. We went out there in January and gave a lecture and a workshop at the museum. I was pleasantly surprised to see how many “regular people” were attending the museum – there were a lot of families and folks that don’t fit the stereotypical art audience. It was also a lot higher attendance numbers than I’ve noted at similar institutions. Free admission probably helps but you could tell they were doing a lot of outreach. And from the conversations that I had with attendees, the museum seemed to pull from a wide regional audience, rather than just the immediate surroundings.

I have to say that I had some initial trepidation about the exhibition, given that the museum was founded by Alice Walton and that she also chairs the board. It can be hard to think about the labor politics that made all that philanthropy possible. But from my observation, the curatorial vision and collection acquisition is independent from those influences, and my experience with them was nothing but positive.

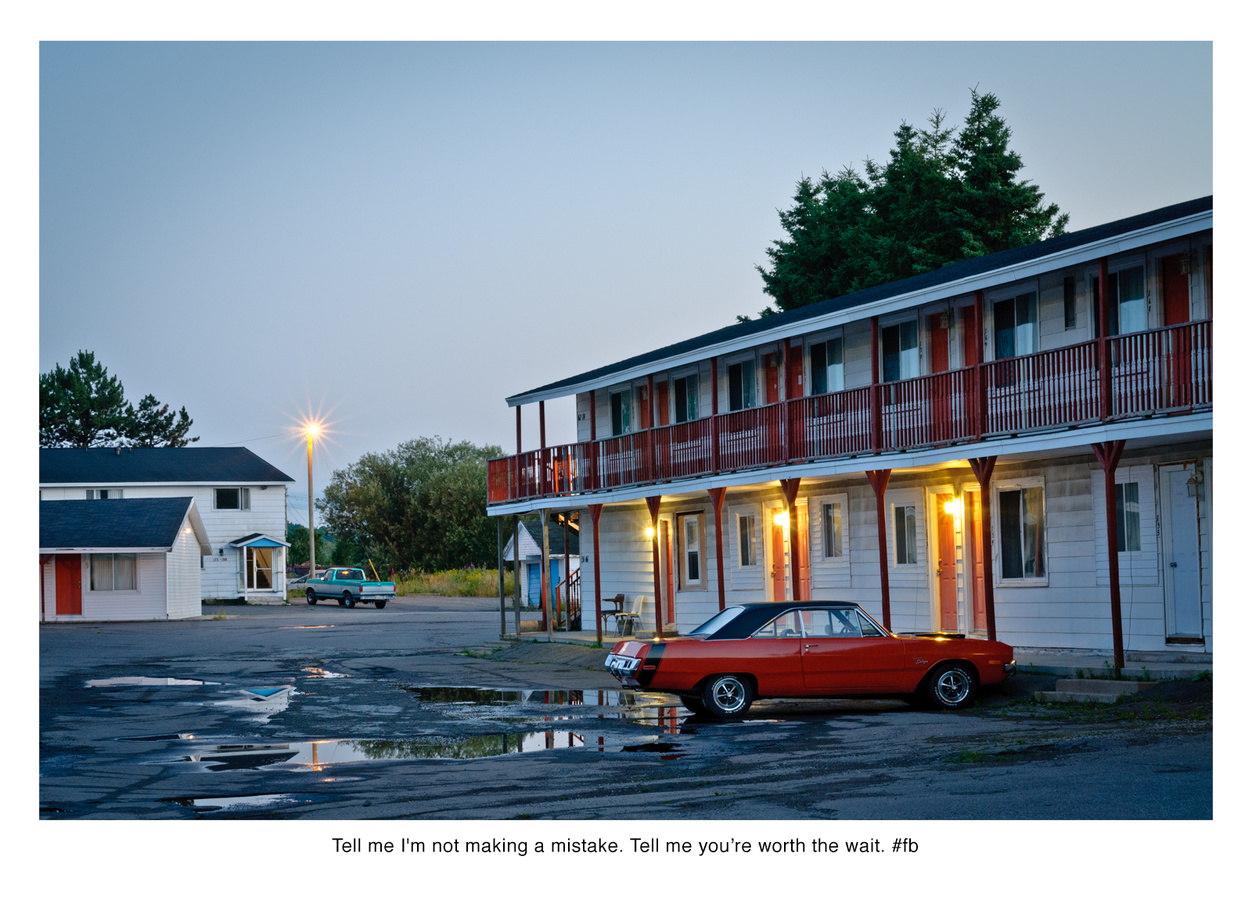

Also, I took time to photograph on our short trip to Bentonville. Some of the photographs online here: http://www.natelarson.com/walmart.

DB: How do you use social media as a part of your practice? You post your experimental writings, #AirportTrueStories #AmericanExcept #BaltimoreStormPrep #OnlyAtArtSchool on the Instagrams and Twitters, but what about the other images? Is it really just a visual diary?

NL: #AirportTrueStories is something that I’ve been doing for the last 2-3 years on Twitter as I travel. I’m thinking about them as photographs, even though they’re 140 character writings without images. But they fill that photographic impulse for me, to document something seen, to record a strange occurrence. It became a way to break up the monotony of travel and to think about little bits of writing as a document. I also think there is a relationship to poetry.

I’m not really sure where this fits into my larger practice, but it’s been fun to do, and I posted them to my website to see how they feel in an art context. I haven’t exhibited them beyond the presentation on my website, which is selected from many more in my Twitter feed. I experimented with several graphic forms of the texts before settling on a format that is a bit of an homage to John Baldessari’s paintings in the late 1960’s.

With my Instagram, I don’t really think about it “as art” but it’s definitely a part of my practice as a sandbox or a playground to think through ideas. It functions as a visual blog, a repository for photographs that I’m compelled to take that don’t fit in anywhere else. I also use it as a reminder of lived experiences or chance occurrences that I don’t want to forget.

DB: Can you talk a little bit about professional practices, or at least how you keep track of the artists you meet and keep in contact with?

NL: Well, I learned a long time ago that not everything happens right away. Timing has to be right for a gallery or museum to work with you, both in terms of their programming and your current projects. I’ve met curators before where we liked what each other did, but it took ten years before the right project came along to work together. So relationship-building and keeping in touch are essential activities for any artist.

I started keeping track of all the art-types that I meet in a monster spreadsheet, which can be sorted by city or state. Artists are in one tab, curators are in another, and press in a third. When I travel to do a show, lecture, or make work, I try to keep in touch with the people in those regions and build those relationships. I have a big mailing list too, but I’ve found that it’s better to be specific by geography. People are interested when you’re doing a show in their community, but less interested when you’re doing a show thousands of miles away that they can’t possibly go to. So I try to be specific and be personal when I sent announcements.

Also, you never know where opportunities might arise, so I try to support the professional activities of my contacts as much as possible and I hope that they will do the same for mine. A rising tide lifts all boats, right? I’ve shown my spreadsheet to my students a number of times and it seems to have taken on legendary status in some MICA circles.

DB: What kind of projects/things do you have coming up?

NL: Well, I’ve got a vast notebook of things that I’m jotting down all the time and a vast folder on my computer with all kinds of clippings.

As I think that I mentioned to you in an earlier conversation, I’m working on an artist book this summer that makes a photograph for each of the 211 homicides in Baltimore in 2014. I have the block notations from a Baltimore Sun archive that pulls them from the police reports, so my photographs are based on that information and are within a block of the site. I hope that it is an elegy for all those that lost their lives to violence in our city last year.

I’ve also been reading up on Prison-based Gerrymandering, where inmate populations are counted where the prisons are, rather than their home communities. Since the inmates cannot vote, that leads to a distortion of apportionment of representation, giving the communities around prisons outsized influence. I’m going to be thinking about this issue a lot in my studio practice this summer.

With Marni, we’re thinking about how social media is used to organize for social justice, looking at hashtags like #HandsUpDontShoot and others that circulated after the events in Ferguson. We’re also thinking about how technology marks the sites of mass disasters, for example the Brazilian nightclub fire that had 800-900 cell phones ringing in the aftermath. This line of thinking came out of reading a CNN article and we made this video piece: http://www.larson-shindelman.com/first-responders. We’re currently working on more related pieces, based on the dual role of the cell phone both as a primary witness and trace of a victim.

During my fall sabbatical from MICA, I’m the Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel Visiting Artist Fellow at Duke University and will be using their special collections and archives to look at land use and population development over the history of our nation.

Author Dwayne Butcher is an artist, curator, writer, chicken wing connoisseur and newly obsessed home brewer. His work wittily comments on his life as a citizen of the American South, usually around issues of gender identity. He recently had an exhibition, Daddy Missed My Birthday at the David Lusk Gallery in Nashville, TN. Organized by Erin Goldberger and opening in June in an old Chinese video store on Mulberry Street in NY, he will be showing some of his video work on VHS tapes. That should be fun.