** At this point, Amy has a new heart and is in recovery mode. Thank you for all your help and contributions and please keep them coming! If you are able to contribute to Amy’s Mid-Atlantic Heart Transplant Fund, or would like more specifics, click on the link to HelpHOPELive here.

* It is mentioned near the end of the interview that Amy Sherald suffers from a heart condition that is life-threatening. Although we were planning to save this interview for the spring 2013 opening of Amy’s work, now part of the permanent collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, Amy’s physical condition has deteriorated to the point where she has been hospitalized and is waiting for a heart transplant.

Amy Sherald was raised in Columbus, Georgia and currently lives and paints in Baltimore MD. She moved to Baltimore on a whim and ended up at the Hoffberger School of Painting, studying with Grace Hartigan and graduating in 2004. She has lived a bit of a charmed life, working as an apprentice to artist-scholar Dr. Arturo Lindsay during her undergraduate years at Clark-Atlanta University where she earned her BA in Painting. She followed up her MFA studies with a private study residency with painter Odd Nerdrum in Norway.

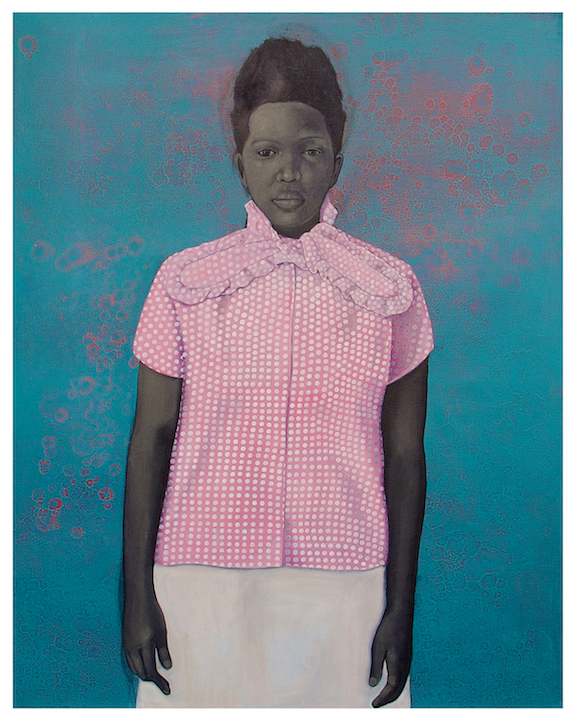

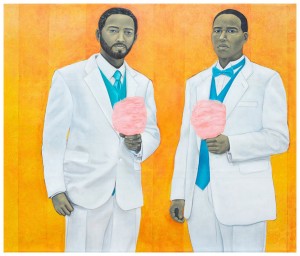

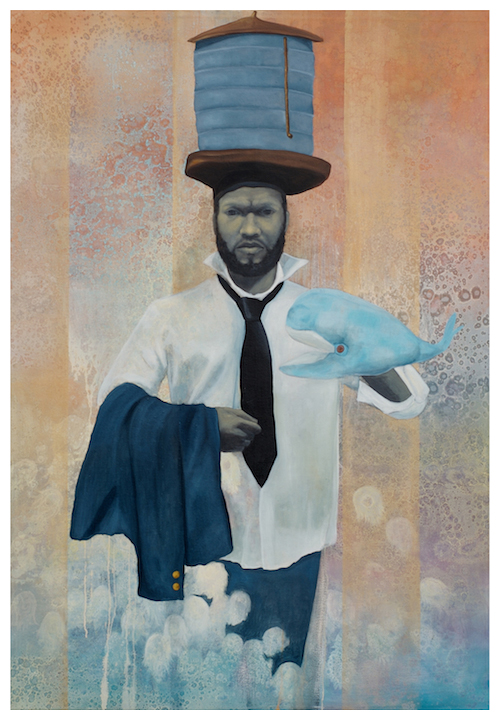

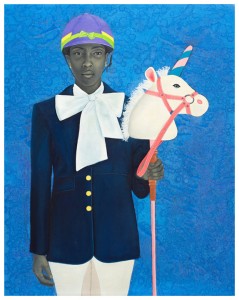

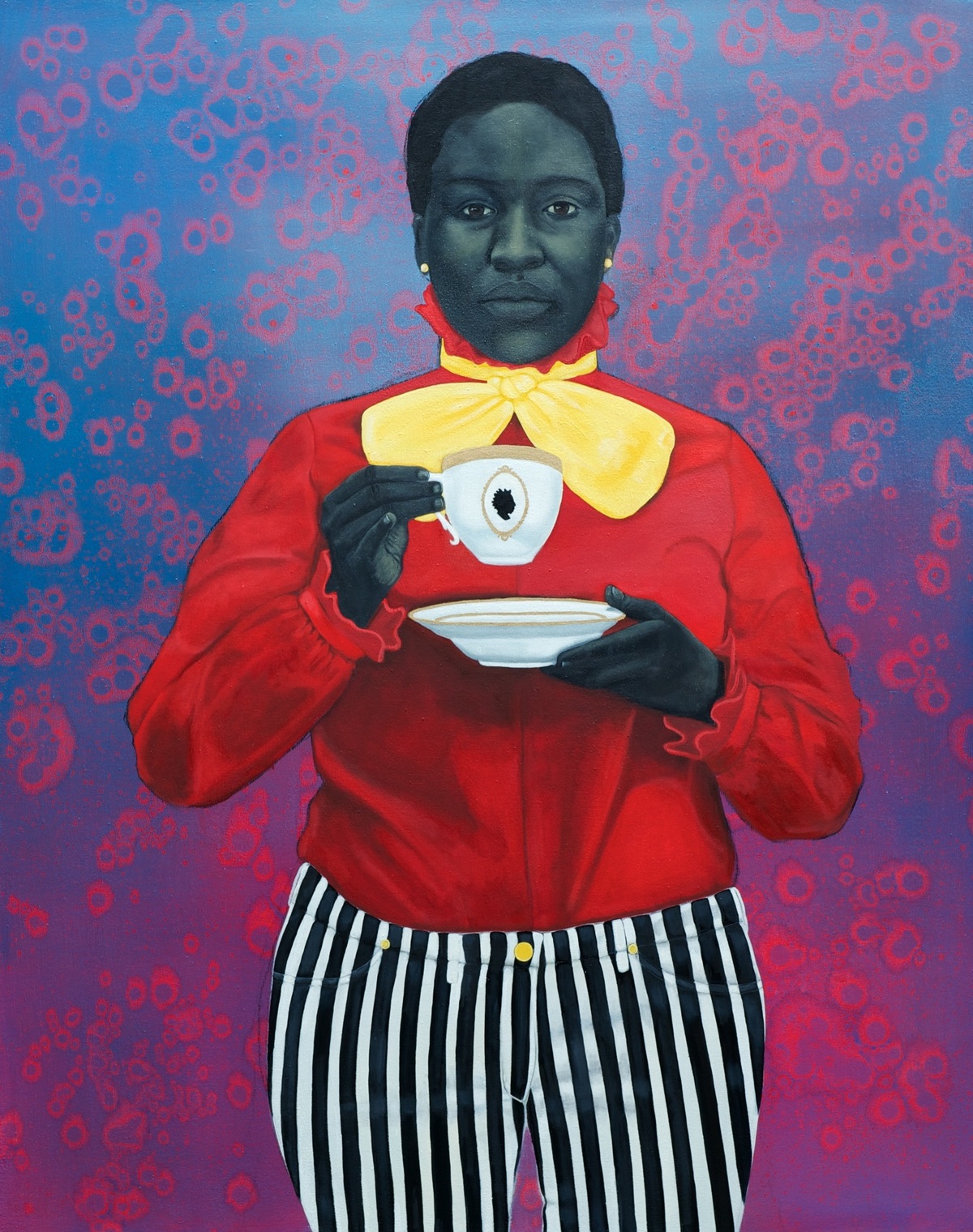

I discovered her work about six weeks ago when my graduate (MFA) mentor mentioned her striking portrait work. Her life-sized portraits of African American figures dressed in slightly unusual or fantastical costumes fall into a category of magical realism. The figures in her paintings are generally standing, facing forward, confronting the viewer directly with their gaze. The backgrounds are beautifully painted surfaces that place the figures in a dream-like state of imaginary space.

Sherald uses color expertly throughout her paintings on the many fabrics, patterns, clothing and props she includes, but she purposefully does not use any color in her subject’s skin tones. You can see that their features are African American but their skin tones are all painted in a neutral gray. Amy Sherald says in her artist statement that she chose “to exclude the idea of color as race from my paintings by removing ‘color’ but still portraying racialised bodies as objects to be viewed through portraiture. These paintings originated as a creation of a fairytale, illustrating an alternate existence in response to a dominant narrative of black history.” Her work is currently featured in the “Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe: The Contemporary Response” exhibit at Galerie Myrtis on Charles Street in Baltimore.

JC: Have you always been a painter? When did you discover your love for art?

AS: I didn’t grow up going to Museums, it wasn’t like art was a thing that my parents were into. I had generic landscapes from Ethan Allen hanging over the fireplace. I had art lessons—it was my favorite thing to do when I was in school. And it’s what I had a proclivity for but I didn’t go to my first museum until I was in college, no, I went on a field trip once and then in college.

The first time that I did go, I think I was in the sixth grade or something like that, and it was to the Columbus Museum. I guess it had just opened and there was this artist named Bo Bartlett, who is from Columbus. He’s very well known now. He studied at the Pennsylvania Academy. He paints on a large scale: figurative work, realism, narrative kind of works. He had this painting called “Object Impermanence.” It was a painting of a house with a woman standing in front of the house and you don’t know whether she’s the mother, but she’s a white woman standing in front of the house. A white kid on a bicycle who looks about eight years old and then a black man standing there in the front yard. He is standing there just looking out. I don’t know why I was affected so much by it—maybe because there was a black person in the painting. I have no idea, but I never forgot it and from that moment on I knew that I needed to paint big and that I needed to make these paintings. I wasn’t necessarily drawing figures well at that age or anything like that, but that moment made me want to be a figurative painter. That was it. That, literally, was it.

I don’t sit around and obsessively read art books per se. I make work based on my life experiences and it just happens to be relevant to a current discourse of identity, you know, but I didn’t really try. I never really took African American Studies Classes. I hate feeling like I have to feed into a certain brand of blackness that I feel like the art world promotes. I am trying to be anti-that. I am not a lover of art, I mean I love going… I am going to see Ai Weiwei [at the Hirshhorn] tomorrow. I’m excited to go see Ai Weiwei! I love Yayoi Kusama. But I feel like all these artists have work that is biographical. So it’s really about the same experience as me watching the documentary, “Ethel” and it’s not about the art. It’s about what the person experiences in their life and what comes forth from that.

JC: You have worked with some wonderful mentors including Dr. Arturo Lindsay, and Odd Nerdrum. How did you luck in to that? …get that great opportunity? …and what was the most influential part of working with these artists?

AS: Charmed life! I never tried to do anything. I had my mind set on it though. I didn’t discover him (Nerdrum) till grad school and I found him in the library and I don’t know what attracted me to his work because it so foreign image-wise, palette-wise—it’s just so foreign. I think it was just that feeling that he talks about: he calls work heliocentric and geocentric even though those were terms used to describe Aristotle and the discovery of rotations of the sun and the moon. He feels like geocentric work is work that is localized. It is like Andy Warhol’s brillo pad boxes—you have to be of the time and in the moment to understand how to interpret the work. It’s his sense of the timelessness. I was attracted to that sense of timelessness and spirit in his work. His work looks like he could’ve painted it 500 yrs ago or painted it yesterday. You can’t really place it in time.

I found his work and I was looking for a way to do an assistantship when he came to MICA to give a lecture because he had a show at Forum Gallery. I got there an hour early and hoped to run into him. It just happened. He just happened to be walking with a professor who introduced me and he asked me what I was going to do after grad school. And I was like, “I’m coming to Norway to study with you!” and then I ended up giving him a ride to the train station that night. I wrote a proposal to go work with Nerdrum and ended up getting a $3000 artist grant to go to Norway. I learned more from him than I did in my whole school career in 4 months and I think it was because I got to see him start his painting. I was also working with students coming to Norway from the Florence Academy. I was pre-Med till Junior year when I changed my major and then Arturo was nice enough not to make me take all these other classes because I had two years.

I never really had any formal training in painting. Everything I did was just through my eye—and I have a backwards way of working because of that but I got to see how he started a work and I got to learn about light and shadow and color and how specific he was and it just really helped me tighten up my practice. Then I didn’t paint for three years when I got back ‘cuz I had to go take care of my mom and my aunt and my great aunt and my dad had died. There had been all this familial drama but it’s like whatever happened in Norway just transcended me and when I started painting again it wasn’t a struggle. I had hated painting before because my drawing was off; this thing was off; that thing was off; my color was off; I didn’t know how to make white — and now I know that I start with blues and yellows and I build up to this thing. Anyway painting is easy to me now and I enjoy it because of watching this man paint.

Luckily I also had Arturo so I was able to gain valuable experience. If it hadn’t been for him, I wouldn’t be here right now. I begged to work for him for free. I had these great opportunities because he would have a show in Germany and he would need me to go to the Museum of Contemporary Art Panama by myself and be down there for two weeks hanging a show.

JC: I saw that you had installed and helped curate a show in Panama on your resume and I wondered how that came about?

AS: I’m just lucky. My work was so horrible then but Arturo just admired my drive and I just did it. But, I didn’t take advantage of a lot of the people I came in contact with because I was so self conscious and shy that I would just scurry away as soon as I was done, you know. It was enough to make me realize that I needed to take my work more seriously. Just letting me exist within his world was a huge influence. He showed me what it really meant to be an artist, what the world was like for an artist inside of a working system.

JC: It seems like being published in New American Paintings and being the Juror’s Pick really boosted your career to the next level. Is that what led you to a NY show? Was that the thing or were there other factors that you got you to this point?

AS: Yeah! That was it. I wouldn’t have a career right now, I mean how else do you get national, umm, FREE national publicity like that? How else does it happen? It doesn’t.

JC: Did you feel at any point that you had that artistic breakthrough…in grad school or after?

AS: I was just painting, I had all this work and I didn’t know what I wanted to paint—I just knew I couldn’t make bald-headed paintings of myself anymore so it took me the first year (back in Baltimore) just to figure out what I wanted to paint. From the three years that I spent not painting, just reliving that experience of being in southern Columbus, Georgia, I had all this stuff in my head. Then I saw Kara Walker’s exhibition and then I thought I don’t know what to do with all this information! How do I fit into this, cuz that’s not me. I’m an escapist. I love the Teletubbies—the idea of grass with no bugs make me happy, you know I like feeling like i have the ability to dream and fantasize.

That year was the worst year of my life because my self-esteem was shot, I could never be suicidal…but I felt that way…but I couldn’t figure out what I was doing. I was in the studio 8 hrs a day and it was just like crooked. So I’m reading, watching movies, whatever, and it finally came together. I had decided to start this series of paintings of lynchings. I thought I could make these reverse lynching paintings and I did one, that was the “Hangman.” But in my head I had this conversation that I had with a fellow artist who had this burgeoning career—he’s been in the Whitney Biennial and he was selling his paintings for $30,000. Then he decided he wanted to change his work. His galleries dropped him and before you know it, two years later he was driving a snack truck. So, anyway, he said, “When you think about the work you wanna make, make sure it’s something you’ll be able to expound on for the rest of your life.” And so I’m trying to figure out what it is that I could do that I won’t get bored with and I won’t feel like my gallerist can control me with and that I can continue to make interesting work.

So I went from lynchings to thinking about circuses. I went to the library to look up books about magicians, black magicians or black circus performers and there were none in Enoch Pratt (Library) and so I ended up renting the movie “Big Fish,” cuz I love that movie and I thought, I’ll just watch this tonight instead and that was it! I just opened it up—and I had seen it before—but I just opened it up and it had these circus stripes on the inside and I just had this light bulb moment watching it! And I thought this is what I want…I want the freedom to have this kind of experience inside of myself.

JC: So your big breakthrough came while watching the movie “Big Fish”? It wasn’t anything that happened in Grad School?

AS: Yeah. Grad school wasn’t a flop really, but now I feel like I’m ready for grad school. I wasn’t really ready for grad school back then because I literally went from coming out of college; making maybe like 3 or 4 paintings in 6 years; working for Arturo; then deciding I wanted to go to grad school; then moving to Baltimore on a whim 2 weeks after my dad died; and then painting these really awful paintings in somebody’s garage in Pikesville. If I even had a clue what I was applying to, like in my head, you know, I am an artist, but if I had seen the work of the other artists that were there, I would probably have shriveled up and died and not even applied. But I did the interview and she (Grace Hartigan) asked me what I had been doing and I just started crying because I started talking about my dad being sick, and she just liked me, she saw my potential and my passion.

JC: So Big Fish was the A-ha moment?

AS: I was just trying to figure out my existence, my awareness of my blackness in Georgia and how it became so different just because I was in Georgia. I grew up in this very racialized environment, but it kinda wasn’t. My best friend was white. I didn’t have any Black friends until I was in the ninth grade so I had this weird liminal space of either trying to prove my Blackness to Black people or trying to do the other for White. And I’m not mixed but I got teased like I was mixed too. People would call me a ‘zebra’, ‘bumblebee bitch,’ and ‘old yellow,’ and so I had all this and I needed to figure out how that existed inside me and what it meant. Then on the other hand, coming from the philosophical perspective, recognizing that race wasn’t something that I wanted to embrace per se. I needed to be able to break it down like I did with Religion.

The fact that my parents raised me Christian and to believe that Adam and Eve were the first people on the earth and the world is 5,000 years old,and why if I can disbelieve that, then why can’t I disbelieve this construct that I’ve been living in my whole life and never questioned because I was raised in the South. Because I was the only black person in my classes, because, you know, of having my best friend be White and going over to her house and having her sister say, “I don’t want that nigger in my bedroom,” and so I would just be like, let’s go play outside, you know. What does all that mean? What does race mean? Is it the way Kara Walker presents it, like this kind of sadistic, nasty, raw, history? Yeah that’s all there but how is that serving my person now? How can I negotiate my life based on that information now because my world doesn’t represent that now.

I am at MICA and there’s low percentage of black minorities. Sometimes the only other faces you would see would be working in facilities management. There is a separation, but in this micro-narrative, everything is hunky-dory. Then there is this larger narrative where it gets complicated, and then you just kind of live it out. Life exists between the cracks not in the bigger spaces, and so I’m just living between the cracks because the cracks is where reality is. I’m not a stereotype. I should feel free to say what I am, I should feel free to say that I am a German-African-American. My grandfather was half German, my great grandfather was German. I am a product of the dirty south, of race mixing of slavery. I can’t say that because I’m in America and they see my Blackness differently here because of that. I can move through the world and not even think about it, not even have to think about how I see myself in a southern perspective. I see people looking at me like I don’t belong there even if that’s not what they are thinking. I’ve been influenced by that history. I don’t feel that way when I’m in other places…just when I am in the south. I am thinking about it from that perspective.

Becoming aware of race, gender and identity and then figuring out where does it all belong, what to give relevance to, is difficult. I don’t want to be just black. How do we keep from being viewed as just these two races? Can we make it more kaleidoscopic? I feel like I am making a rough draft now. These paintings are the piecing together. They are all the parts. Sometimes the work ends up being more grounded and more geocentric than I want it to be. The more reading I do, the more the paintings kind of lose that fantasy element.

JC: Galerie Myrtis asked you and several other artists to respond to the exhibit currently at the Walters Museum in Baltimore, “Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe.” Do you think it was a more interesting way to work or was it more constrictive?

AS: It was really hard for me to make the work for Galerie Myrtis exhibition because I had to respond to something. It was constrictive. I didn’t like that feeling, but appreciate a challenge. I made ‘Welfare Queen’ which is hanging in the show, but I want to get back to work more magically real like the characters in Big Fish. I don’t want to make portraits of black people—does that make sense? I want to make portraits of people who are interesting and who have stories to tell. I bought these goggles. I have this idea of this time traveler guy. I want to get back to the fun part. I don’t want to be working inside of post-blackness and art gibberish. I can’t take it.

JC: So you think of these costumes ahead of time and then you look for a person who fits that look?

AS: Something about them I like. Yeah, it’s never really anything I can exactly point out. For the most part, I know what I want them to wear and if I’m not ordering the costume, I’m vintage shopping looking for the pieces to put together and then I dress them and shoot them.

JC: You photograph the models and then work from the photos?

AS: Yeah.

JC: Do you do any live sketching at all or do you just work from the photos?

AS: I’m so bad with that, I don’t. Everybody’s like, you need to sketch, and I’m like, what’s the point? I already know what my idea is. My sketch is the photograph—but I do want to do more drawings: larger and smaller drawings because I have those moments when I look at an artist’s work and I think, if she had a smaller piece, I’d totally buy that and then I point at myself, like, you need to make some smaller pieces. So my painting got better also because I stopped painting from an actual photograph and I started painting from my laptop. So when I am painting a hand, I can actually zoom all the way, all the way, all the way, in and then I can get all the little lights and reflections. All those little details add up. It’s probably why painting became less of a struggle too because technology helped me become a better documenter of information.

JC: I assume you are familiar with Barkley Hendricks’ work? He worked in much the same way where he also “found” his models on the street or by chance. He chose people based on their “look” or fashion. Although he sometimes embellished or exaggerated their costumes within the painting, I don’t think he pre-conceived costumes for them but he did alter the clothing in his paintings. He also paints very realistic yet flat figures facing forward. How much did you look at his work or did he influence you at all?

AS: I discovered his work when I went to a show he had at the Studio Museum in Harlem. In that year, they had paired up a poet with an artist to write a piece in the Museum magazine, so I was invited to the exhibition and that’s when I first saw his work… and that was 4 years ago or so. It was amazing. Kindred spirit.

JC: So this was after grad school but was it before or after you began the ‘Big Fish’ series?

AS: Yeah, I had already started.

JC: Your skin tones are purposefully not varying shades of black. Hendricks painted black skintones as he saw them , dark or light, or whatever. You have a specific mixture of black and naples yellow that you use to create your neutral skin tones. How did you come up with that?

AS: I had this friend who suggested that It would be easier for me to paint flesh if I painted everything in a grayscale first so he said to just use black and naples yellow because if you use just black and white, it comes out too silvery. And then I did it and I liked it just the way it was. I don’t know about anybody else’s art making experiences but mine has just been random, non-profound. The gray skin tone works for a number of reasons. It works because of all the other colors I am using and then it works because it helped me play with that idea of taking away color and what it meant.

JC: Kerry James Marshall works with skin tones in a similar way by painting all blacks as the same dark black. Did his work influence you in any way?

AS: I saw his work when it was at the BMA. It was at least 8 years ago. I was excited to find out about him also… I want to go home and look at his catalog again right now. He is brilliant.

JC: How did you decide on the scale of your works: life-sized and larger? Is that important to the impact of the work? Or do you just not like painting small?

AS: All of the above. I think it creates a different kind of experience. I want it to be more confrontational. It’s kind of hard to have confrontational work if it’s like you are peering into something vs. walking up to something. You have the opportunity to feel like its encompassing you. And then again the first painting I saw and fell in love with, that painting was huge! It was 7 x 7 feet or something like that…so also from that moment I just wanted to make large paintings. I just don’t like to work small even when took a sculpture class in college they wanted us to start with these small little things but I had this idea to make this large multi-level thing.

JC: Unlike Barkley Hendricks’ work, you don’t give us the whole figure down to the feet. Is that because it is easier than moving around 6 ft tall canvases or? Is it a conscious decision to crop the figure?

AS: I had a few that are full-bodied. I think part of it is practicality. And then it is less shopping for me. I didn’t have to find shoes that make sense with the costume. Some of these costumes are just hard to come up with and so I think it was for practical purposes and I needed to find a size that was big enough that it satisfied me but small enough that I wouldn’t go broke. Making big canvases costs a lot of money. And, it fits in back of a car. It was all of those three things.

JC: Tell me about your painting, “They Call Me Redbone But I’d Rather Be Strawberry Shortcake” that has just been donated by collector and gallerist Steven Scott for the permanent collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. How exciting is this for you and how did this come about? Was that one of your favorite pieces?

AS: It’s hands down been the public’s favorite piece. So many people see things in that young woman’s eyes. I’ve always been a little critical of myself about it. I was not that “love” with it because it didn’t have the props that I had in the other work, and so I liked while I was painting it but then, you know, as you do more work then the last one is always the worst.

JC: How did the connection happen with Steven Scott and the museum?

AS: I had a show. Every year at the Pennsylvania College of Art and Design they do a project called the Mosaic Project and invite in two artists of color to participate. It was me and another artist Raul Colon who is an illustrator. He saw the exhibition and called me and said he saw the painting and he wanted to buy it and also share my work with the curator at the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA).

JC: So you didn’t apply? They just found your work and invited you?

AS: Again they saw my work in New American Paintings

JC: Steven Scott personally wanted to buy it? Not his gallery?

AS: No he wanted to acquire it. He liked the work. He has a relationship with several museums, and I met with the curator at the National Museum of Women in the Arts and she made a studio visit and liked what I was doing.

JC: So there is no guarantee that even though she came to your studio and he was willing to donate it, that they would accept it?

AS: Right no guarantee. Fortunately, they both agreed on the same painting and the museum committee accepted it into there permanent collection. The right collectors can be your biggest advocates.

JC: Where/how many times have these pieces been exhibited yet?

AS: Redbone was exhibited at my gallery in NY at Sag Harbor that I’m not really with anymore. Both of them were shown there and at UNC Chapel Hill. Nowhere close enough that I would deserve to be in a museum! It was just luck.

JC: But Steven Scott didn’t ask to represent you and your work in his gallery? He is not interested in the retail side of your work? This is just his collector side?

AS: No my relationship with him is solely as a collector.

JC: Do you think that other museums will knock on your door this spring after seeing your work at the NMWA? or other collectors?

AS: Yeah, I’ll let you know! Because I am just winging it. I don’t really have a plan. I just make sure that I go to the studio everyday and apply for stuff when it comes up. Because I know that’s important even if you don’t get in—you have like four people on the jury from the artworld looking at your work.

JC: So you’re just winging it— you don’t really have a plan?

AS: Isn’t everybody else just winging it too? (laughter) There is no approach. You can’t just walk into a gallery and say I am interested in showing here… if you can’t do that, what do you do? You just go to your studio and hope somebody will find you and you apply to things that you know can get your work out there. If I hadn’t applied to New American Paintings… my jaw dropped when I opened it up and saw my work featured! I was shocked that I even got in! It just so happened that the curator on the jury got what I was doing, again I just got lucky!

I believe that if I think it, it will just happen somehow. I believe in just NOT stopping painting! Sometimes I look on FB and have panic attacks ‘cuz it seems like they are so smart and they are reading this and doing that and showing here and showing there but your reality is your reality and your work is your work and you’re gonna reach a certain point in your work and you’re going to be able to apply for stuff and its just gonna start to happen. You just get random phone calls and then you’re like, o.k.! and so I don’t like to take credit for anything ‘cuz i didn’t do anything.

JC: If Strawberry shortcake wasn’t your favorite one, do you have a favorite painting currently? or is your favorite one, the next one that’s on the easel?

AS: I believe my favorite one is probably going to be this next one that I’m going to do of the Tin Man—my self portrait as the Tin Man. I just want to get back to the fantasy part. I fall in love with them and then fall out of love with them and I’m on to the next one. I can’t stay in love too long ‘cuz then I just want to keep it. I am making a profit. I feel like I’m a machine, like a hand tool, right now. I feel like I need to find another passion, like playing the saxophone ‘cuz its a job now and its not like I don’t enjoy it. I get a lot out of it but when I don’t do it I feel lost and feel depressed, then realize I haven’t been in the studio for five days, but it’s work. It’s nine-to-five work.

JC: But do you do other work?

AS: Not right now just painting. I keep my life simple so that I don’t need much. this is probably all because I’m going to die young. That’s my hypothesis.

JC: Well this leads to my last question: I understand that you are facing life-threatening health issues. In fact, you are on a waiting list for a heart transplant. Has this impacted the direction of your work?

AS: Not yet… I don’t know how to paint about that part of my life. I don’t know how to paint about sickness. I feel like by doing that, it makes it real. I feel I’m an escapist.

JC: You just mentioned the Tin Man, though?

AS: Yes, but that’s fantasy, though. He needs a heart and so do I.

I talked with Amy Sherald in a small neighborhood cafe near the MICA campus about her paintings and her experiences along the path of her artistic journey. We discussed the performative nature of identity. She revealed how she feels that she has to put on a certain persona depending on the situation or who she is with and how that has fed into metaphors of performance in her work. We discussed the autobiographical content of her work and experiences that she had as a light-skinned Black girl in the South. We talked about the price of her works and how to interact with galleries and collectors. We discussed the confusion an artist can feel in graduate school when so many different voices come into the studio. I listened as she told me about her daily life as an artist and how she manages to sustain herself from one painting to sale to the next. Through good fortune and being in the right place at the right time she has found a studio to work in and a home to live in without having to work a full-time job. She has simplified her life to just waking up and painting. Painting is her job. This Spring Amy Sherald will have two paintings in the permanent collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC.

– Joan Cox is a Baltimore-based painter, currently enrolled in an MFA program at MassArts.