According to Merriam-Webster, the word festoon behaves in two different ways. It can be a noun, “a decorative chain or strip hanging between two points” and “a carved, molded, or painted ornament representing a decorative chain.” Or, festoon can be a verb, meaning “to cover or decorate (something) with many small objects, pieces of paper, etc.” Both the nominal and active uses of festoon are highly relevant in the collages and drawings by Zöe Charlton in her new exhibition titled festoon, currently on display at Connersmith Gallery in Washington, DC.

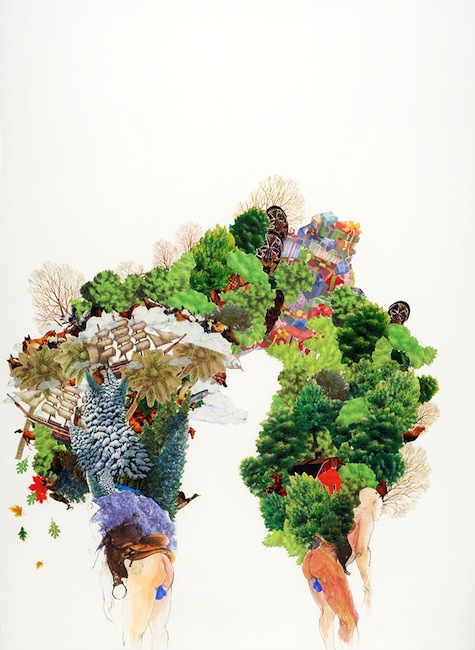

Somewhere between fantasy and metaphor, Charlton depicts festooned human figures caught in a balancing act, carrying the weight of cultural histories on their backs. In “Anhaica,” two men, one black and one white, face opposite directions, each struggling to move while sharing a tentatively balanced arch of intertwined images of on their backs. Rather than a backpack or bundle, the mounds they carry are a visual delight: collaged images of lush green trees of North American and Tropical varieties, colonial ships, wrapped gifts, African masks, Western horses, and a red barn all pile into high and precariously balanced towers. The collage elements, small illustrations and photo-style stickers, have been playfully arranged on top of the figure drawings, so that they are literally festooned. If that weren’t enough, the men are harnessed with saddles and saddlebags. They are otherwise nude, and carefully rendered in pencil and light washes to indicate subtleties in skin color and musculature. However, observed color deviates in their genitalia: they have shockingly bright blue balls, a sign of the frustration each feels from being tied together or from the heavy burdens they carry. The white negative space around the figures and their festoons gives Charlton’s smallish 30×22 inch works a tremendous sense of gravity and spaciousness.

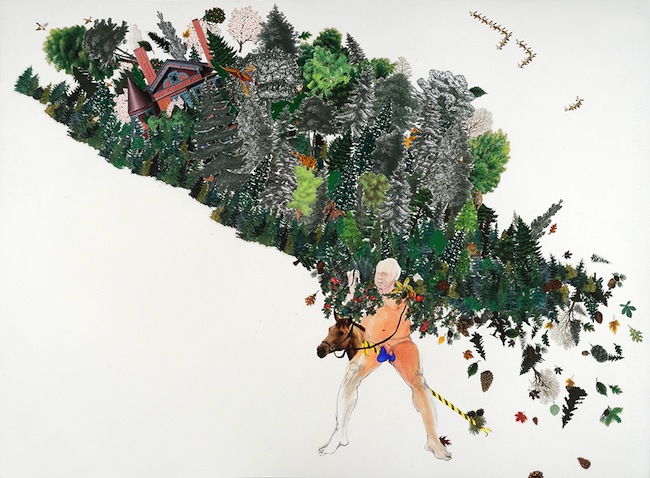

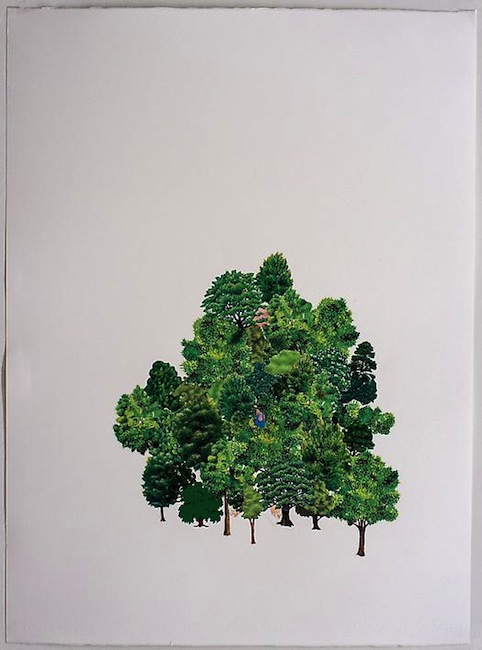

In “Wakulla,” a single middle-aged male leans forward in a servile position under the ridiculous weight of an energetically sprouting group of horses, pine trees, ocean waves and birds. Like a contemporary Atlas, he is simultaneously doomed to carry his own cultural history while being the source and foundation for the growth of the future. Additionally, Charlton’s blue-balls metaphor is at work in several of the other pieces in this show, in some cases subtly hidden and glaringly obvious in others. For example, “Woods” is filled with a seemingly innocuous grouping of trees. Only close inspection reveals a bit of a man’s face, feet, and blue balls emerging from behind the camouflage. He seems to be a giant in the woods, spying on the viewer from a hidden perch. These works incorporate curious juxtapositions of imagery that refer to colonialism and the clash of cultures. They also make you want to lean in closely to observe all the tiny details, to attempt to puzzle out the message from a range of symbols. Each little bird or tree seems heavy with meaning.

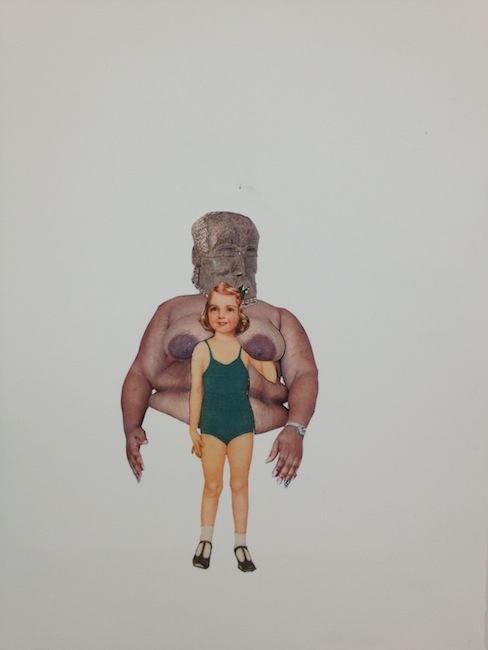

While these first pieces address only the male figure, Charlton’s second body of work in this exhibit deals only with the female figure: specifically White girls and Black women. In fact, this second body of work incorporate three distinct series using the female figure as the primary subject. In the series entitled “Rear,” Charlton utilizes the images of vintage paper dolls of a young White girl in collage works where she wears the nude torso of a Black woman as a backpack or as a protective shield. In several works, she appears nestled between large African breasts and, while the little girl may seem to be sheltered by the figure on her back or simply content to wear the African woman on her back, in “Rear #6” she seems to be attempting to escape the burden. Charlton has also replaced the Black women’s faces with African masks, making them universally and culturally “other” to the All-American White girl.

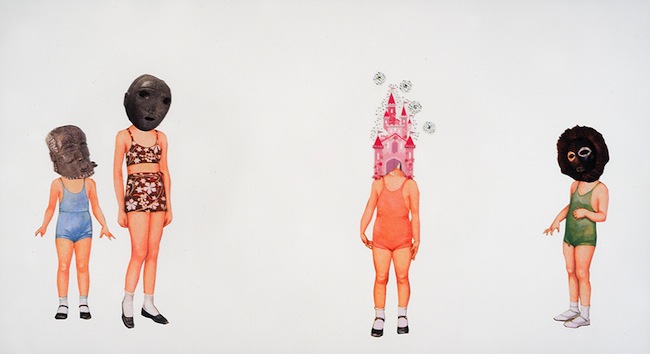

In the series, “Those Girls,” some of the paper doll’s heads have been replaced with glittery stickers of pink castles, while other girls wear African masks and stand around her with their heads hanging low. Lastly, in her “Homebodies” series, the paper doll girls are caught in the process of transforming into Suburban homes. Their bodies are replaced with walls and rooftops of suburban homes, leaving them locked in place. The small figures appear to be trapped by the American dream, unable to escape their inevitable futures.

Those Girls #1

It is no accident that Charlton chooses young girls for this series rather than depicting grown women. She addresses common cultural expectations: Who should be when we grow up? What we should want? The images also recall historically dominant patterns of non-whites (nannies, housekeepers) raising white children. Charlton asks the viewer to consider a number of different roles and conflicts playing out in her scenarios. Do we want the glittery castle or the suburban dream home? Will we ever get it? Is it even worth wanting? Are the little girls standing proudly or excitedly with arms out or do they hang their head? What we perceive as viewers is dictated by the smallest details of the carefully assembled collages. Charlton relies on heavily on metaphor and subtle figurative expressions to evoke conflicting feeling about the situations she presents.

Although divided by sex, both bodies of work in festoon address uncomfortable issues of race relations in contemporary American culture, but through a unique sense of humor that comes off as both naughty and nice. Charlton hones in on imagery that makes the viewer feel uncomfortable right away: explicitly depicted male genitalia, large breasted African women, and explosive forces of nature. The images are also full of the cheekily nice: sparkly bubbles, birds, clouds, landscaping, and dreamlike, beautiful imagery. Although they are uncomfortable, many of the situations Charlton creates have a wicked sense of humor. In “Fort Mose” a man stands attempting to balance an armload of trees, property, and a gorgeous home on his back, all while riding a hobby horse with his blue balls prominently on display. In spite of all the laughs, Charlton pulls the trigger by including racially divided imagery that recalls slavery and colonialism, pairing up African masks and pink castles to create a mythical, horned fighting beast in “Satisfactual.”

Despite the stature of collage in the art world and a rather small size, Charlton’s new works pack a punch, effectively calling attention to the classist roles still playing out in contemporary society. Additionally, her use of scale imbues the figures with power, with tiny ships, horses, houses, and trees, transforming the men into mythical giants. The power is abruptly stripped away by depicting nude figures in the midst of struggle, shame, or confusion.

While Charlton decorated and collaged these works with little bits of stickers and paper in a classic festoon fashion, she hints at a derogatory interpretation of the word too. Charlton creates characters who can be viewed as festoons themselves: overly adorned figures who are almost laughable in their predicaments.

…………………….

festoon is on view at CONNERSMITH in Washington, DC through November 2, 2013.

Hours: Wednesday – Saturday 10am – 5pm

* All images above Copyright Zoe Charlton, courtesy CONNERSMITH.

** Author Joan Cox is a Baltimore-based painter and a graduate of the MFA program at MassArts. Her work is currently up at Goucher College’s Silber Gallery. Photos below, from the opening reception of festoon are courtesy of Joan Cox.

Artist Zöe Charlton and Author Joan Cox at the opening of festoon

Artist Zöe Charlton and Author Joan Cox at the opening of festoon