There’s been a lot of discussion recently about small and mid-size galleries being driven out of Chelsea by rising rents. While I don’t doubt that it’s true, you wouldn’t necessarily know it from walking around the neighborhood. It’s still so densely packed with galleries that, if you happen to be there while it’s raining, it’s not even worth opening your umbrella between stops. You can stay relatively dry just by hopping from one gallery to the next.

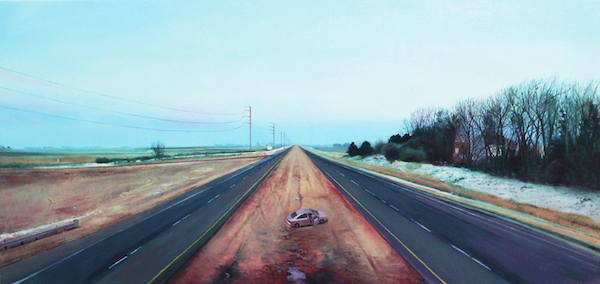

One of my first stops on the rainy day I happened to be there was Anna Zorina Gallery. Their current exhibition, Places Unknown, is the first New York solo exhibition by Nate Burbeck. Burbeck is originally from Minnesota and his paintings of suburban and exurban landscapes reflect his midwestern roots. In his landscapes, suburban housing, built with a uniformity that betrays their recent construction, dot nearly tree-less streets. Gas station signs peek out from behind patches of trees in otherwise serene settings. While these calm vistas might normally suggest serenity, the sparsely populated scenes contain a strong feeling of ennui. The occasional inclusion of unsettling or unusual phenomena—two children huddled over a fire set in the middle of a road, a large billow of smoke emerging from an air conditioning unit, a farmhouse on fire— shifts the mood from bored to undeniably threatening.

Burbeck’s work has obvious precursors. Photographer Gregory Crewdson is a clear influence and is cited in the press release, as are Angela Strassheim, Rackstraw Downes, and the film Blue Velvet by David Lynch. There’s a whole genre in the visual arts (let’s call it suburban surreal) that explores the aesthetics of the American suburbs and exurbs and mines the visual patterns in those landscapes for evidence of listlessness, disenchantment, and creeping violence. (The fascination with the dark undertones of suburban life transcends visual art and film—think of Arcade Fire’s 2010 album aptly titled The Suburbs.)

Burbeck’s approach to the genre employs a welcome subtlety. While the influences of Crewdson and Lynch are apparent, his paintings counter their unease with moments of real sublimity. There is something appealing about these spaces, a reason inhabitants prefer them to crowded city life. His depictions borrow some characteristics from more romantic approaches to landscape; it’s his human figures that look especially ill at ease. They’ve manipulated these environments for their own purposes, the paintings seem to suggest, but are now unsure of how to exist within them.

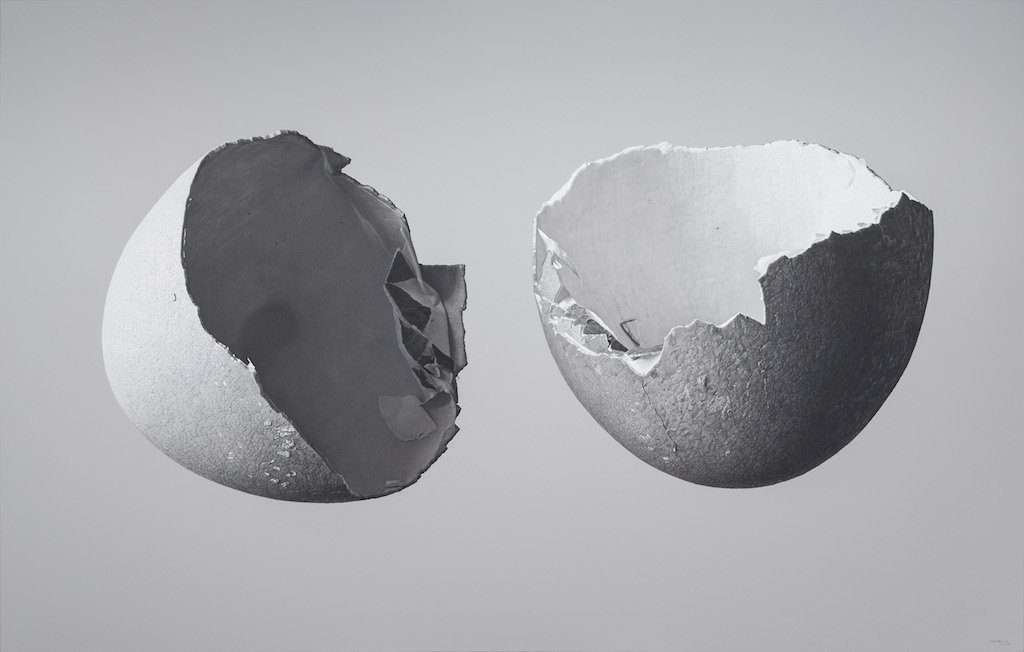

(Image at Top: Rómulo Celdrán “egg shells” : Zoom XXIX, 2013. Pencil and acrylic on board. 48 x 75 3/5 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and Hasted Kraeutler, NYC.)

Not far away, Hasted Kreutler Gallery shows work by another artist with a clear lineage whose work transcends sheer imitation. Rómulo Celdrán is a Spanish artist whose interest in the materiality of everyday objects is reflected in stylized over-sized sculptures and hyperrealist black and white drawings, both depicting mundane items. Celdran’s large objects bring to mind Claus Oldenberg, an influence Celdrán nods to with several pieces featuring clothespins.

While the sculptures, with their shiny surfaces and familiar shapes, are more visually spectacular, the graphite drawings are the standout works. Celdrán’s drawing of an orange slice is so lovingly crafted that each individual pod seems ready to burst. A broken eggshell is depicted with a near-microscopic level of detail. Celdrán presents the surface of this object, which typically winds up in the trash, as an entire world in and of itself.

The artist’s fetishistic treatment of the mundane acts as a sharp reminder of our position in the physical world and near constant engagement with the objects that surround us. In an age when we spend an amazing amount of our time staring at screens, gazing at pixels organized to represent physical objects, these works insist on drawing your eye back to the material world. While there’s a certain whimsy at work, especially in the oversized sculptures, the pieces also evoke the sheer abundance present in our consumer-oriented landscape. Whether as hyper-realistic pencil shavings or oversized ice-cube trays, Celdrán’s pieces alter the physical relationship we’re accustomed to having with these objects, giving them a gravity that demands our attention.

At C24 Gallery, Skylar Fein’s The Lincoln Bedroom includes a useful introduction, for visitors who might not be up on historical debates about Abraham Lincoln. It begins:

From 1837 to 1841, Abraham Lincoln and Joshua Speed shared a bedroom. Famously, or infamously, they also shared the bed.

As the introduction explains, historians dismissed the significance of this arrangement for years, insisting it was just a consequence of the scarcity of beds in a small frontier-era town, at a time before physical closeness between men was presumed to indicate a sexual relationship. This explanation has left other historians unconvinced. Fein is less interested in declaring Lincoln’s certain homosexuality than in using the historical fact of his bed-sharing habits and the dismissal of its significance, to explore historical shifts in how we think about gender and sexuality.

The anchor of the exhibition is a physical re-imagining of the famous bedroom. You can walk up a set of stairs and into a re-creation of the room, complete with a hay stuffed mattress on a narrow bed. The actual building that housed Lincoln and Speed’s bedroom was destroyed and there are no available images, so the re-creation was designed based on images of similar buildings from the same time period. As Fein points out, that this building was destroyed, while the house that Lincoln shared with Mary Todd in the beginning of their marriage was preserved, is itself significant. The act of recreating the cabin highlights the way historical knowledge is constricted. Featuring signage that mimics the large didactic text more common in history museums than art galleries, the installation is an attempt to intervene into the creation of history and invite us to consider what we can’t know.

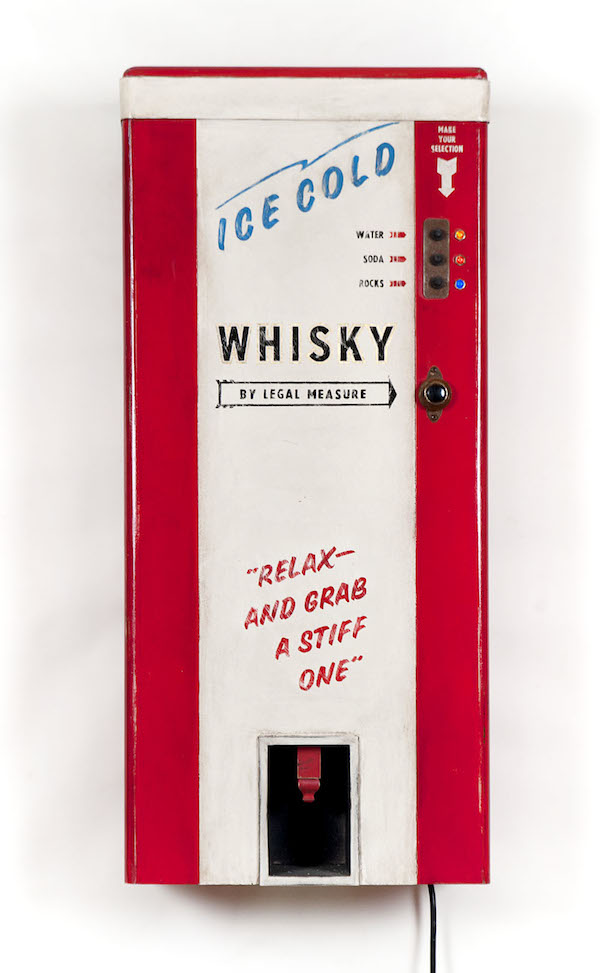

While the recreated cabin is the largest presence in the space, Fein’s other work reaffirms his approach to history, creating a lens through which to read the cabin itself. These other pieces include recreations of actual historical objects and objects meant to appear antique but constructed with anachronistic features. Ice Cold Whiskey Machine appears, at first glance, to be an actual antique. While the object itself is a re-creation, it’s based on an actual whiskey-dispensing machine that was manufactured as late as the 1950’s. On the other hand a sign for the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands look as if it could be a historic artifact – until the viewer realizes that the signs is electrically lit, a feature that wouldn’t have been possible during the time when the advertised department existed. Fein’s reproductions of surprising and altered artifacts highlight the difficulty we have in truly understanding the past. There are facts that we can know about history, but our understanding of it is always impacted by our own assumptions and the limitations we place on our investigations of it.

Links:

Nate Burbeck: Places Unknown

February 20 – March 25, 2014

Anna Zorina Gallery

533 West 23 Street

Rómulo Celdrán

February 13 – April 12, 2014

Hasted Kraeutler

537 West 24th Street

Skylar Fein: The Lincoln Bedroom

C24 Gallery

514 West 24th Street

Other recommended stops:

Kianga Ellis Projects

516 West 25th Street, Studio 306B

Eyebeam

540 West 21st Street

Eyebeam is currently preparing to move to Brooklyn, (link here) so visit them in their current space while you still can. They haven’t announced a timeline for their move yet, but they’ll likely be out of their current space by the fall of this year.

Printed Matter Inc

195 10th Avenue

PPOW

535 West 22nd Street

Alexander and Bonin

132 10th Avenue

Bitforms

529 West 20th Street

The Kitchen

512 West 19th Street

Winkleman Gallery

621 West 27th Street

* Author Blair Murphy is a writer, curator, and arts administrator who recently relocated to New York City from Washington, DC. During 8 years in DC, she worked for a number of local arts organizations, including Washington Project for the Arts, DC Arts Center, and Provisions Library. Read more at blairhasablog.blairmurphy.com and follow her @blair_e_murphy.