Dwayne Butcher Interviews Amanda Burnham about her latest project, RFP at EMP Collective

Amanda Burnham received her MFA from Yale University in 2007. She is an Associate Professor and Foundations Coordinator at the Department of Art+Design, Art History, Art Education at Towson University. Burnham has exhibited her work at the Volta Art Fair, the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, the Delaware Center for Contemporary Art, and regionally in places such as School 33, MICA, Maryland Art Place, Hamiltonian Gallery, and Transformer.

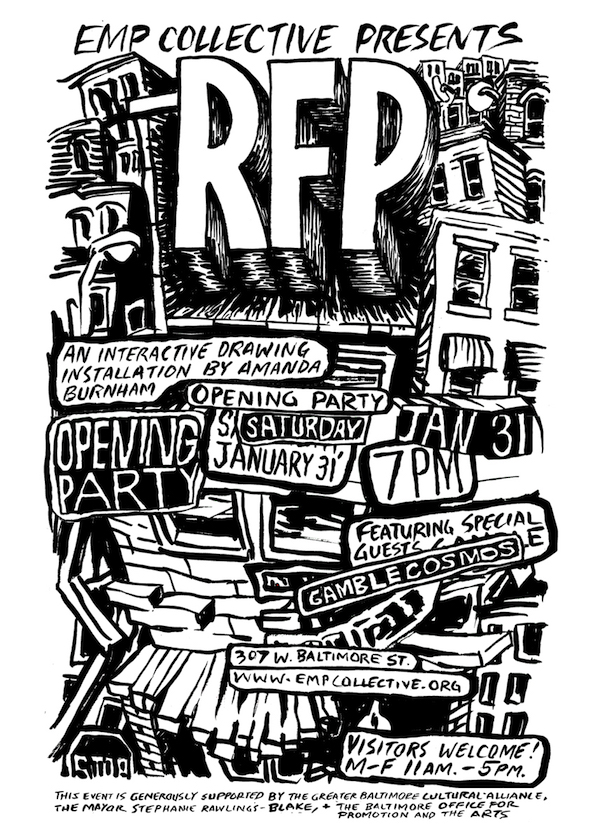

She is currently working on a large-scale installation that is scheduled to open Saturday, January 31 at EMP Collective. I met her at EMP to talk about the installation, Switzerland, ideal cities, and why the alleys in Baltimore are the best way to get to know the city.

Dwayne Butcher: You are currently working to create an installation to cover the entire 5,000 sq. ft space of EMP Collective. How did you get the idea for the “RFP” exhibition?

Amanda Burnham: The idea for this project came about after getting the chance to do several large, public installations – in particular, a work I did a couple years ago for MAP’s IMPACT program at the Towson Town Center. As I constructed the piece over the course of a week, lots of people wandered up with questions, suggestions, or even just to watch – often repeatedly. I found that I really enjoyed these interactions, and that their content frequently insinuated itself into what I was making. I started to think that it would be interesting to stage a work that was public, by design, over a much longer period of time (most of my installation work is the result of no more than a couple of days of intensive on-site construction) and to make the somewhat performative, collaborative dynamic of these happenstance interactions more deliberate.

And, of course, given that my work addresses cities, as I started to think about this more, the potential for such a piece to function metaphorically began to crystallize in my mind. I’d done projects with students before where I’d work with a group to facilitate the making of a large piece through small ephemeral drawings loosely organized around a theme. Those types of projects always create a great energy in the classroom, as students interact and collaborate effortlessly as a result of sharing space and a common task. That kind of energy is also prone to arise in urban communities, and it’s something I’m consistently drawn to. I thought creating a work that invited visitors directly in to contribute their words or marks could suggest not only the collective authorship of cities but also potentially reveal some interesting opinions through the process.

DB: Is it daunting to think about working in such a large space?

AB: To some degree it is, though I work very quickly and fluidly at large scale – much more so than when I work small (which I also still do). The time scale for this project is absolutely immense in my terms – as mentioned, I am normally lucky to get a couple of days to pull off an installation. I don’t heavily prefabricate these works (other than making tons of raw material to potentially use for collage) because I really can’t start to see the connections between things until I’m actually in the setting. So, getting the entire month of January to go nuts at EMP is absolutely luxurious for me, and, of course, I also get all of February to continually modify it in dialogue with whatever visitors contribute. The hardest and most daunting part was thinking about it in December before I could actually get in and start.

DB: How did the imagery and ideas, at least initially, come about for this exhibition?

AB: I very much wanted this piece to address perspectives on Baltimore beyond my own, and of course the piece is designed to solicit that. It was important to me that the images contained within it on the day it opens be informed by outside perspectives as well, though, which led me to working with a group of area high school students this fall. I spent time with two groups – I joined Elisabeth Gambino’s art classes at ACCE (the Academy for College and Career Exploration) for a month, and was also a visitor to Rachel Valsing’s class at Towson High School. Elisabeth and I collaborated on a unit that focused on community and emphasized the ways that individuals might assert themselves and have a role in the fates of their communities.

We talked about urban planning and community advocacy, and we also talked a lot about what strong communities need to function well. I learned a lot from Elisabeth’s incredibly creative, ambitious lesson planning ideas – we had the students interviewing community members, writing position statements and role playing in a mock community meeting, as well as (of course) drawing to reflect on what they liked about their communities, and what could be improved. The result of the month was a large mural on the first floor hallway of ACCE that voiced their ideas about what a successful community should contain.

DB: Can you talk about the experience of working with these kids? How is it different than working with your students at Towson?

AB: I came away with a lot of renewed admiration for teachers working in city schools. Many of Elisabeth’s students face a lot of varied distractions in their lives, and, as a result, the classroom environment can be difficult to manage, because students don’t necessarily arrive on the same page, with the same amount of readiness. Continually attending to so many divergent individual contexts is downright exhausting.

Everyone knows this (or should), but it is a HARD job. It is NOT a job that most people, I think, are equipped to do well. I was continually blown away by Elisabeth’s seemingly unending reserves of energy and her ability to negotiate really difficult terrain in the classroom. I learned a great deal; while my students at Towson certainly come from diverse circumstances and have distractions in their lives, it seems to me there are more support structures for most of them to cope (as well as support structures for faculty to be as effective as possible).

Difficulties aside, I found the students at ACCE to be incredibly bright and inventive. They are forthcoming and thoughtful about these issues.

DB: What did they think of the future of their city? What stake do they think they have in this future?

AB: Most of the students I talked to tended to think of the city in smaller increments, in terms of what they know – their neighborhoods, their homes, where they spend time and feel comfortable – I’m not sure that they necessarily viewed Baltimore as a larger entity, but then, who does? We all have our own “Baltimore.” I did not get the impression that many students felt as though they had a lot of legitimate stake in the city, but once we got into it, they had a lot of opinions that they were eager to share about what their communities needed.

Many of these were not surprising: athletic facilities and community centers got suggested by lots of kids, as did parks and trees. They want places to go where they feel welcome, safe, and have things to do – which should come as no surprise to anyone, but the reality is a lot of them do not have these resources in their neighborhoods, or they’ve been taken away. A more qualitative reality that became clear to me is how unwelcome many students feel in many areas of the city.

ACCE is in Hampden, but the students who go there are largely from other neighborhoods, and I heard a lot from them about how the reception they get in some area businesses can be anywhere from chilly to downright hostile. None of them cited Hampden as a community they “belonged” to, even though the school is there – it’s a huge disconnect. Of course, so many of these places that they feel a remove from are the same kinds of places that are held up in conversations about neighborhood renewal as being desirable. It’s not that they aren’t, but it’s obvious that there’s a much bigger problem than the literal structures of a city.

The students were very keyed into the needs of others as well as their own wants and opinions. One student, in an urban planning map he made suggesting improvements to his neighborhood, drew an elaborate (and really well designed) park space (with scenic walking paths and such) in the land surrounding a grandparent’s retirement facility. There were suggestions made about the need to add sidewalks, better transportation options, and variations in types of housing stock, daycare facilities. A lot of the spaces they cited as being valuable in their own communities – churches, corner stores – aren’t necessarily the first places that come to mind when a lot of people think about valuable structures in a neighborhood, particularly as neighborhoods gentrify. But these are places that help to engender a sense of community, and they need to be valued.

DB: So, what makes an ideal city?

AB: An ideal city is one where unplanned interactions can happen (and do happen) regularly, because it contains a heterogeneous mix of structures and facilities that are valued and used by a broad mix of people. It’s a city where individuals largely feel welcome wherever they go, and feel both invested in their surroundings and a sense of shared fate with their neighbors. This includes individuals who support a city, whether through government, the police force, or other support services. A sense of shared fate engenders mutual respect and inclusion, so it’s vital that the people who work to structurally support a city come from it, and feel themselves to be a part of it.

DB: There is a public component of this exhibition, the public actually helping to make the work and adding, if they choose, their ideas. But visitors, for the most part, are not accustomed to being able to touch work in a museum or gallery, how are you going to prompt them to participate?

AB: I’m aware of that, and both because of this and because art galleries are one type of place that people often feel unwelcome or out of place, I’m striving to make the installation itself as welcoming as possible. It will stretch to the front windows, the doors will be open, there will be signage inviting people in, music playing. The interactive elements will be made clear, too. Sculptural elements will be on wheels, able to be pushed and moved. Tables with materials, while meshing with the formal framework of the exhibition, will clearly indicate that they are to be used. I also plan to be present during the entirety of the show’s run, drawing, adding things, and initiating conversations with anyone who walks in. The show will be open daily, from at least 11am to 5pm daily (and probably more than that).

DB: How did the idea for working with images of the city come about?

AB: I started drawing stuff in Baltimore when I moved here, because I moved here for my job, didn’t know anyone, was incredibly lonely, and as a result had lots of time on my hands to draw. I also had a 6th floor south-facing walkup apartment in the upper northeast corner of Mount Vernon with an amazing view. So, I spent all that free time drawing out of my window, and eventually got interested enough in what I was looking at that I started actually venturing out and getting to know the city through drawing.

Initially I think I was attracted to these forms because I saw a lot of gutted and abandoned old buildings that I romantically thought sort of allegorized my general unhappiness and isolation (which makes me wince when I reflect on it.) But as I got more engaged with what I was looking at, I became genuinely interested in and excited about the unique architectural qualities of Baltimore as a city. At the same time, I also became more enmeshed in it as a member of the community. I found that I had relationships with my neighbors that were closer and more rewarding on a daily basis than any place I’d ever lived, and I think a lot of that has to do with the physical reality of the city. So, the work started to be about that.

DB: What type of work and ideas were you working with prior to moving to Baltimore? How was the transition into working with the idea of the city?

AB: The work I was making prior to coming to Baltimore also made use of architectural forms, but ones that were fairly iconic and divorced from reality. Baltimore provided a visual referent that I had craved in my work at the time because I’d reached a point where I wanted my drawings to more ambiguously straddle the observed and the invented as a way of achieving greater emotional nuance. So, it felt very natural to start working with the forms of the city.

DB: How do you explore the city now? What are some interesting/unexpected things in Baltimore that you have found?

AB: My favorite way to explore the city is by running, which I took up sometime shortly after I moved here. Running provides the versatility and opportunity for close looking afforded by walking while also allowing me to cover much broader swathes of the city in one go. Walking by contrast can feel a little more parochial as far as the bigger picture you come away with. I also like how the speed and cadence of running gives me compositional ideas as I see structures draw near each other in my field of vision and then separate.

There are a lot of things that interest me about looking at the city but my favorite thing by far is observing the, at times, really extravagant and inventive ways people kluge their homes to solve a problem or allow for a space to be used in a novel way. You see this especially in alleys behind row homes – a weird piece of scrap lumber holding up a sagging porch, homemade outdoor cooking apparatus, elaborate gardens in tiny patches of space. This summer I walked by a porch with a bunch of people sitting in easy chairs facing in towards a window that had an old tube TV positioned in it, so they could watch the O’s game together while enjoying the weather. I love that.

DB: What do you have coming up after the exhibition?

AB: I’ll be documenting the goings on within the exhibition extensively (journaling on the RFP blog, taking pictures, collecting ephemera, etc) throughout the time its up in February, with the general idea of turning that raw material into a book over the months to follow. I don’t know what that will look like yet but I’m excited to find out – it all depends on what happens over the course of the month.

After that, I’m headed to Geneva, Switzerland for three months starting in April to do a residency at the Embassy of Foreign Artists. I plan to travel extensively while there, and have plans for a series of drawings that will also eventually become a book. (I’m really obsessed with the idea of working in a sequential format of late – it seems like a great way to cram lots and lots of little novelistic details in one place.)

DB: So, what will the weather be like while you are in Switzerland and what will you do for supplies?

AB: I hadn’t even thought about what the weather would be like until you asked me just now. Whoops! I should get on that. Okay, I just looked it up, and it sounds like it should be pretty temperate – 50’s and 60’s. That’s a relief. As far as supplies – I’m sure I’ll find whatever I need in Switzerland!

Dwayne Butcher is an artist, writer, curator and chicken wing connoisseur living in Baltimore, MD. Butcher moved here from Memphis in the summer of 2013. In that time he has continued to have international exhibitions, published articles in local, regional and national publications, and curated an exhibition of Baltimore-area artists titled “Bawlmer” at Crosstown Arts in Memphis, TN. To see his work and curatorial projects, visit his website and follow him on twitter @dwaynebutcher.