It’s easy to forget you’re in the presence of art when first visiting Bubble Over Green, Victoria Fu’s solo installation that announces the return of The Contemporary to commissioning and exhibiting work. And I mean that as a sincere compliment. Bubble is a solo show qua multimedia installation that lives at 101 West North Avenue. There’s a pair of neon light pieces, a single-channel video piece viewable on a monitor, and a multi-channel audio/video installation that fills the main room. Alterations were made to the building to make it more hospitable to a contemporary installation, but it’s entirely possible to pass or enter the building and not immediately think art. A good friend said he drove by the intersection and noticed it looked like something was going on there. I imagine other passers-by so wonder.

Now, I want to suggest something slightly odd. For this site-specific work, let’s resist the urge to dwell entirely on the site at first. Yes, the building, built in 1961, originally housed a branch of the Maryland National Bank, and since 1990, according to online records provided by the Maryland Department of Assessments and Taxation, has been owned by a series of Korean business people. It used to house Korean-Sun Travel Services; artist and Contemporary program manager Ginevra Shay, who oversaw the building’s upgrades/modifications, told me that at one time a spa was located in the basement. Since the building is also the former home of the Korean American Grocers and Alcohol Beverage Association of Maryland, which as recently as 2010 was included in Maryland’s Governor’s Office and Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs Annual Report (PDF), the location is commonly referred to as the KAGRO building. It occupies a prime corner in the ongoing urban redevelopment project / gamble branded the Station North Arts and Entertainment District—and that unavoidable fact does play a role in the way we experience Fu’s works and ideas here.

But let’s ignore all that surrounding context for a moment, because to focus on what Fu does at and with the site kinda/sorta turns Bubble Over Green into a highbrow feat of interior decorating. Individually, Fu’s works demand a sophisticated reflection. And one way to get there is, upon first entering the building, to proceed directly to the rear of the gallery space to take in “Bubble Over Green” itself (excerpt), an 8-minute single-channel video loop playing on a wall-mounted monitor.

“Bubble” is a clever use of video. What at times feel like a simple documentation of an artist’s 2-D practice—hands pass across the frame to place a circular stencil on top of something, to cut straight lines into a surface with a blade, to paint areas with a large brush, to drop a cut-out rhombus onto the area—is a subtly woozy trip into the virtual. Very quickly you realize that Fu is performing a number of editing effects on the footage to create its constantly shifting visual field. Colors fade. Layers move and change and shift. Holes appear to be cut into the surface to reveal another video layer just beneath it. None of these observations in and of themselves are particularly profound, just as the techniques Fu uses to achieve them aren’t examples of cutting-edge postproduction virtuosity. We all see much more sophisticated instances of digital image manipulation in movies, on television shows and commercials, and even on our smartphones. What’s curiously troubling is how quickly we recognize what’s going in “Bubble Over Green” and accept it as visual information to consume.

There’s a built in assumption that the screen, the place where cinematic and computer and whatever kind of televisual content happens, is what we’re supposed to pay attention to. The screen’s dimensions, the only area that counts, is determined by technology. The effort to be platform neutral comes into being in part because of the market need for interactive digital interfaces to work on, and the device is the point of consumption. That screen area is what informs us and through which information is exchanged. And as anybody who has watched people read their smartphones while crossing streets, driving a car, or have a IRL conversations can attest, sometimes it feels like nothing else matters except what is happening on that screen.

Throughout this exhibit, Fu slyly attacks the integrity we’ve given the screen. Documentation of her former installation, Belle Captive I , also shows Fu treating the space where moving images take place as a layered Rauschenbergian surface, one capable of evoking time because of its combinations of referents and layers but also of feeling immediately of the present because that visual landscape recalls the world around us. Fu creates similar combinations with onscreen visual language in Bubble.

Questions: Is there a word for the omnipresent moving images-ness of the perpetual now, where time isn’t a variable or a component of the medium but an unavoidable given? When it’s possible for moving images to be casually adjusted and edited by the user?

Simply put, are they still just pictures if we can interact with them? Maybe you’re changing how this article looks on your screen right now. Making the reading area larger without your fingers on a touchscreen. Swiping through the vertical column of the text. Changing the size, shape, and dimensions of the browser. Fu recognizes that our screens — through movies, television, video games, computers, and interactive media — have not only provided us with an extensive visual vocabulary but a lay expertise for manipulating the media that appears on them. And she coyly nods to these gestural interactions with the “Pinch-Zoom” and “Ribbon-Swipe” neon pieces that suggest the screen-manipulations of their titles.

Without wandering too deep into the weeds of how artists have used neon lights, I’m going to make some very broad generalizations: it’s a medium common to commercial advertising, one deeply intertwined with 20th-century capitalism’s risks (that the Neon Museum is located in Las Vegas should surprise nobody), and which is also often used to in the service of text. Allow those ideas to swirl in the mind while considering “Pinch-Zoom” and “Ribbon-Swipe,” and appreciate that Fu has depicted gestural motions of the body that read as immediately as words. In fact, the finger-and-thumb motion of “Pinch-Zoom” is arguably even more universal, not taxidermied by language.

The immediacy of that understanding is quietly intriguing and unsettling. We instinctively assume images have an ability to be understood, cognitively and emotionally. There’s a reason why people, as consumers and content makers, are so in love with infographics and data visualization. Images have the capability of being understood by a broader audience more immediately and effectively than language, and the ease of that consumption comes to mind while spending time with Fu’s installation. Many of us now simply have many personalized screens we use to interact with each other and the world. Fu recognizes that, too. She also understands that analog visual production/ representation/ manipulation, digital production/representation/ manipulation, and computer/ digital device user interaction is all part of a single, seamless visual experience.

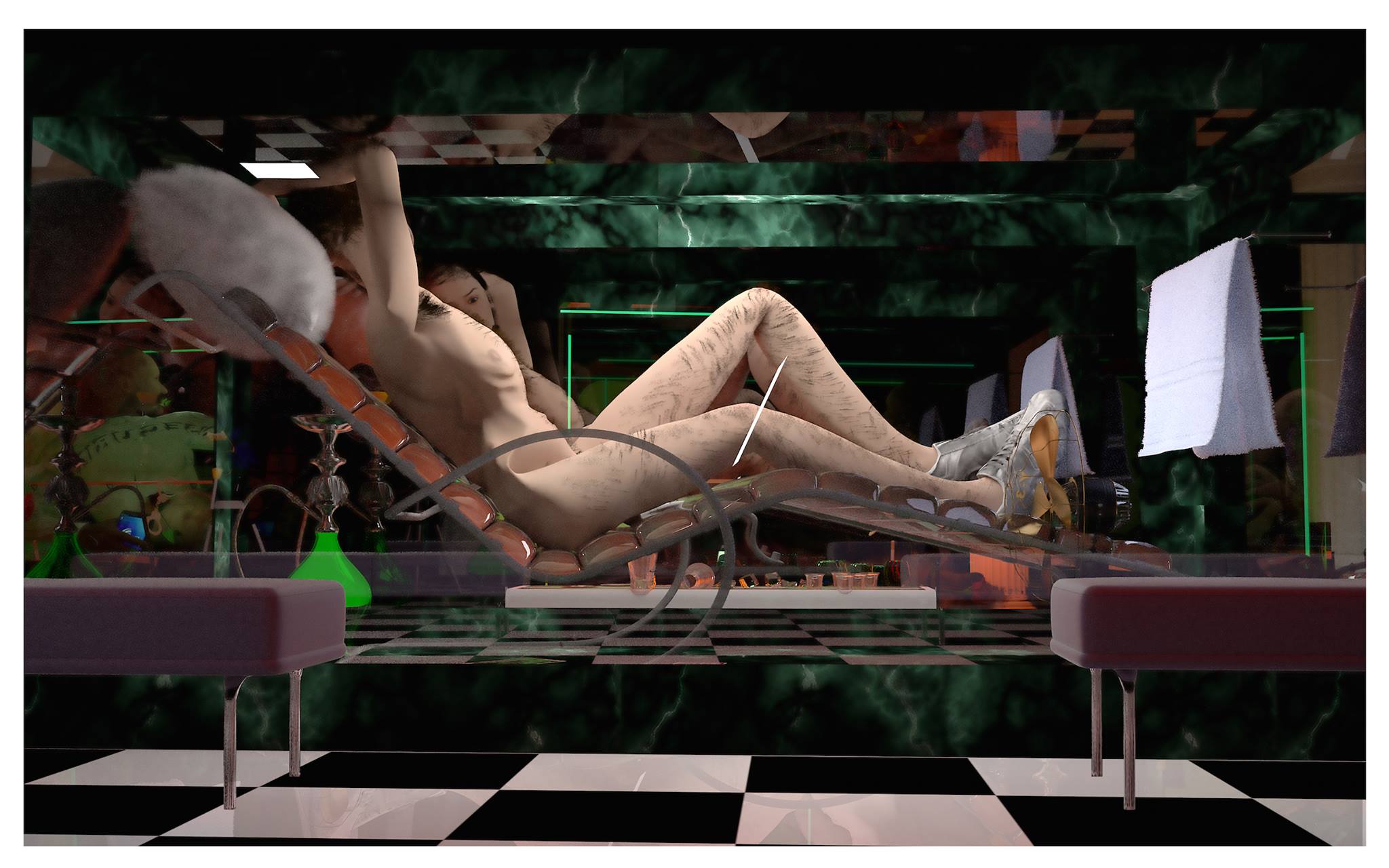

Fu mines this seamlessness most explicitly in “Velvet Peel 1,” the multi-channel 13-minute loop projected onto a stripe of wall near the building’s ceiling, that runs the length of the room. “Velvet” appears to incorporate a number of audio and video inputs. Sounds of water—running from a spigot, falling from the sky and hitting a surface as rain, the plop of an object entering a pool, the swoosh of something moving through a standing volume—cycle through the accompanying soundtrack. Onscreen, some images reinforce what those sounds—a waterfall, a person readying for a shower—but just as often the images don’t. They’re following their own organizational logic.

Numerous different screens pass vertically down the frame. The bottom of a figure wearing jeans is seen, only from mid thigh to just above the waist, in one part of the frame, and then moves to another side. In fact, whenever any human appears, their figures are always cropped: hands and arms only, waist areas only, just the torso, the back of head that a hand touches, etc. Those hands and bottoms sometimes wiggle and shake, sometimes causing the entire frame to shake accordingly. Sometimes there are gorgeous scenes of nature. Sometimes there’s a pair of dancers involved in an odd, stilted choreography. Sometimes footage of the Station North area rumbles across the screen. If you pay attention it becomes quietly hypnotic. But if you’re involved in conversation it’s remarkably easy to ignore.

I’m wondering if that element of it, the ease with which the mind can push it to the background, is intentional. “Velvet Peel 1,” a non-narrative video loop riddled with non-idiomatic actions and abstracted images, couldn’t be anything other than art and yet it doesn’t demand to be consumed that way. In fact, with its rush of sights and sounds “Velvet Peel 1” could feel like a randomized collage of images and sounds, and if you don’t pay attention it starts to take on an ordinary nebulousness. Think of walking though Times Square where there’s a rash of screens and signs vying for your attention, though you can perfectly carry on a conversation with whomever you’re with.

In that scenario, all of Times Square’s inputs become a single feed backgrounded by the brain, even though they’re trying to inform you. Brand something. Tease a _________ (movie, play, musical, book). Warn you when not to cross the street. Point out where to queue for the bus. Tell you what time tickets go on sale. Advertise.

Make that advertising important above all else. Images, moving or still, sell, and our screens these days double as points of purchase — which is a roundabout way to return to 101 West North Avenue. This address has always been a place of commerce, and even if Fu has successfully transformed it into something like a movie theater, let’s not forget what kind of space American movie houses often are: the place where cinema distracted the working classes.

That technology has allowed the personalization of the screen means we now have a playful, fun, dazzling, inoffensively distracting way to consume images individually, and these instruments of consumption offer the passive illusion of interactive control. I can make stuff with the imagistic content I consume and even share my own content with others, but in order to do so I have to buy into the commercial infrastructure and commodity chain that supports it. Being a plugged-in participant in the interconnected world of images means being shipwrecked on consumerism.

And I’m wondering if Fu is shrewdly spotlighting that illusion of agency. She recognizes that images have long been the lingua franca of international commerce, traveling across geopolitical borders and through time. Fu’s approach to images and how we consume them, for me, is tangled up with how they’re used to sell ideas—be they ideas about products/entertainments, ideas about art, ideas about religion and the cosmos, or even ideas about urban renewal. The positive and negative polarity of economic development projects such as Station North tend get talked about in terms of the visual.

“The neighborhood remains sketchy-looking, even as an estimated $65 million has been invested into it in the past few years,” wrote reporter Jacques Kelly in the Baltimore Sun recently. “But it’s that Baltimore rough-and-tumble appearance of authenticity and the feel of being on the edge that so many people like today. In this, Station North is something of a 2015 version of what the foot of Broadway in Fells Point was like in 1970.”

The brain is very adept at creating meanings for how things look by comparing it to things we’ve already consumed: nostalgia is comforting for a reason. Fu’s works short circuit that positive feedback loop through her efforts to violate the integrity of the screen, through intentionally creating images that don’t easily fall into a easily digested narrative framework, and by reminding us how easily we let them become background noise if we don’t instantly assume them familiar. And maybe we need the reminder to pay more attention to what were making and consuming visually.

Fu’s works suggests that being more critical as consumers and makers would create better insight into the commercial enterprises going on around us — because if you don’t recognize that image making is inevitably entangled in socioeconomic points of view, you’re merely regurgitating advertisements for the status quo. Our omnipresent images possess persuasive power, and if you merely let them turn you on, you might not be able to tell how they’re turning on you.

Bubble Over Green will be on view through April 3, gallery hours Wednesday–Sunday 6-9 p.m., with a closing reception March 27, 7-10 pm. Find more info at The Contemporary’s website. “

Author Author Bret McCabe is a haphazard tweeter, epic-fail blogger, and a Baltimore-based arts and culture writer.