Jamie Wyeth at the Brandywine River Museum By Rachel Sitkin

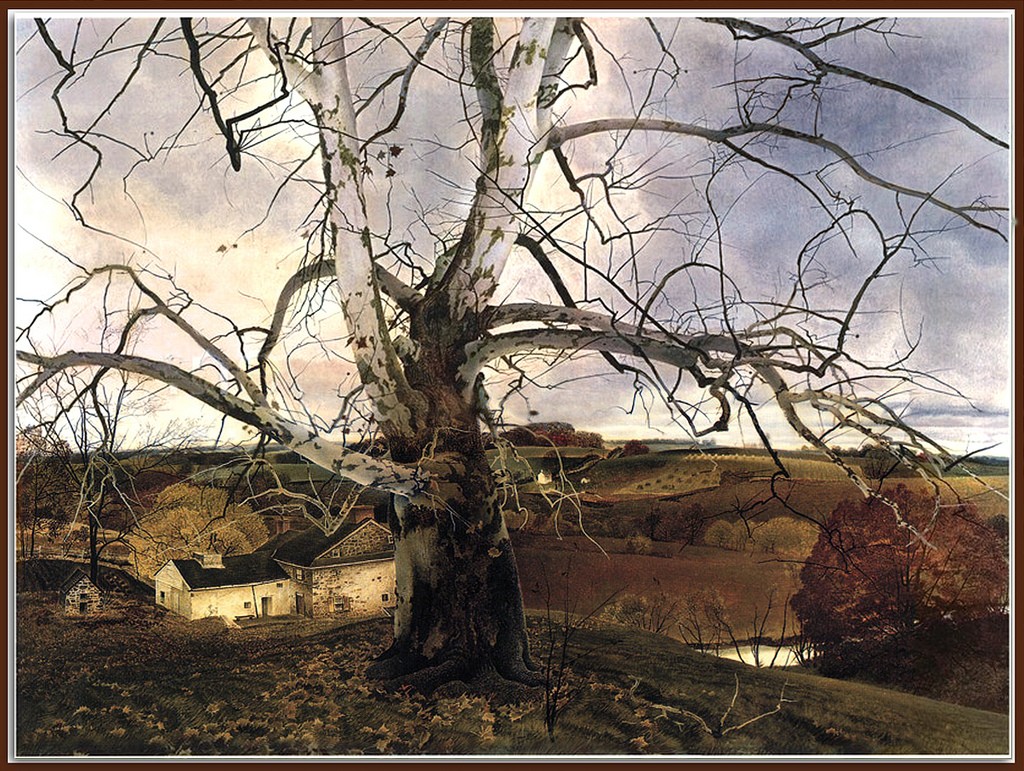

As I drove onto the grounds of the Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, the classic scenes of Andrew Wyeth’s paintings came to life around me. Winter is still lingering; the dusty golden grasses of Christina’s World and the brittle bare branches and weathered barn sides that populate so many of his paintings are omnipresent here.

I wanted to see this show because every time I’ve encountered an Andrew Wyeth painting in person, I lose myself. Standing before his work is a transcendental experience for me. I still count the 2006 retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art as one of the most enjoyable museum experience of my life, and many small details of his paintings remain etched in my mind. I had never seen any of his son Jamie’s work in person and I was curious as to how it would compare: if not for the Wyeth surname, would this be a show worth seeing?

This exhibition was designed to distinguish Jamie’s from the work of his father and grandfather, Newell Convers (N. C.) Wyeth and none of the elder Wyeths’s works are present. The stated objective of this show was to “…understand personal evolution as an artist in relation to the history of American Art… and reveal the creative process by which an artist shapes his personal vision over many years and through a range of media.” Curated by Elliott Bostwick Davis of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the exhibition comprises over 100 works that span over 60 years of the artist’s life, and across many thematic and stylistic changes.

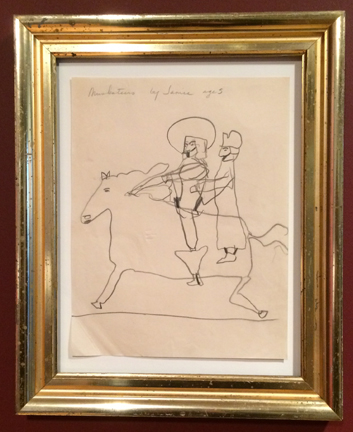

The show opens with a set of five drawings done when Jamie was just a child, ages 5-7, lovingly notated and stored away by his mother, Betsy, who must have foreseen the painterly footsteps her youngest son would follow. Jamie, born in 1946, is the third generation of the Wyeth dynasty of painters.

Trained in the family tradition of “Unapologetic Realism,” Jamie’s work is similarly illustrative and dramatic. At his own request, Jamie was homeschooled after completing the 6th grade, so he could spend more time in the studio. He apprenticed with his Aunt, Carolyn Wyeth, who was N.C. Wyeth’s most studied pupil. His first studio was the anteroom to his father’s (and formerly his grandfather’s) studio. By age 13, Jamie already demonstrated a skilled hand and was studied in the painting techniques of his father and grandfather, as well as Netherlandish painters like Jan van Eyck and American masters Thomas Eakins, Howard Pyle, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and John Singer Sargent.

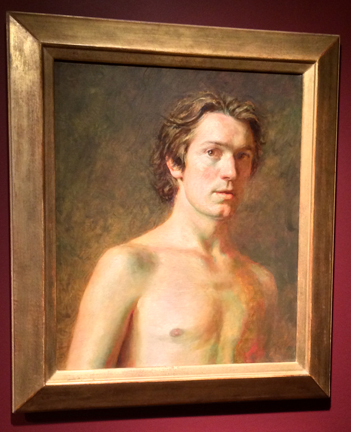

The early portraits on view share the crispness of much of his father’s work. The surfaces are paper thin, and the technique is masterful- especially when you consider that they were created when Jamie was still a teenager.

In a video interview, Jamie said, “I look at myself as a recorder. I just want to record the things that interest me in my life.” And much of the work in this exhibition reflects his surroundings- his childhood in the Brandywine River Valley, his stint in New York City, and now his time split between Northern Delaware and Maine.

In the early 60’s the Kennedys took notice of Jamie Wyeth’s work, and after J.F.K was assassinated, Jacqueline Kennedy hired Jamie to paint a posthumous presidential portrait. Though Jamie declined the official assignment, he did create his own portrait, finally acquired by the MFA in Boston just last year, and included in this show. Accompanying the piece are a series of pencil drawings of Ted and Robert Kennedy, created while on a political tour with the president’s younger brothers.

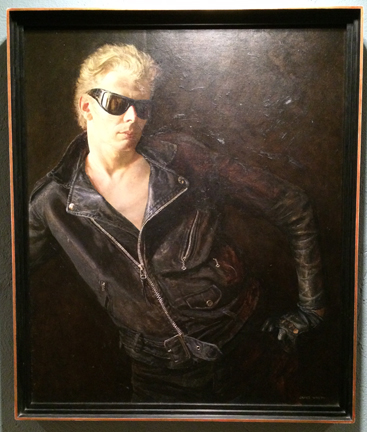

In 1965 Jamie moved to New York City and fell in with Andy Warhol and The Factory scene. A large selection of paintings and drawings, as well as two recently created tableaux vivants, are dedicated to this time. Jamie’s virtuoso portrait of Andy Warhol, and Warhol’s pop-art screen printed portrait of Wyeth are hung as a pair.

The juxtaposition of Wyeth’s hyper realistic portrait of Warhol with Warhol’s graphic rendition of Wyeth serves to illustrate what is so interesting about Jamie Wyeth’s career. He has shrugged off the criticism that his work is irrelevant or out-dated, and instead has embraced his stylistic lineage. He does not respond to changing trends in the art world, though he is most certainly aware of them and maintains close relationships with many contemporary artists. Far from contrived, he has simply chosen to dedicate himself to an authentic depiction of the world in which he lives, and that world is the mostly unchanged bucolic landscapes of his upbringing. He maintains a very rigorous practice, waking daily before dawn and slogging away in the studio for hours. His lifestyle maybe a throwback, but his work is utterly sincere.

The second part of the exhibition is a large selection of animal portraits and landscapes created on his family farm in the Delaware Valley and in coastal Maine, and a few portraits of his wife, Phyllis.

Jamie often paints with watercolor on cardboard or rag board, using thick impasto application rather than thin transparent washes. A series of paintings from the late 1980’s and early 90’s, among them “Twins, Birdhouse,and 10 W 30,” is especially striking as a stylistic departure.

Around this time, Jamie’s work loosened, the paint application is less labored and academic, and the spirit of the sitters becomes the dominant force of the work. While the most distinguishing characteristic of Andrew Wyeth’s work is his seemingly infinite compiling of delicate, deliberate marks, Jamie Wyeth’s work gives itself over to the subject matter. As his style has developed over the years, his own distinct marks have become less intentional, the surfaces less labored, and the result is an honoring of the soul of the sitter, be it his wife, his dog, a sheep or a bale of hay. He protects the autonomy of his subjects with respect and a highly focused attention to the individual’s personality, and the resulting paintings appear egoless.

In a time when so much of the work that we see is social commentary, or re-appropriation of images, or blatant forgery, it is refreshing to see work that feels so raw and honest, that dares to document a guileless version of our current moment.

After exiting the galleries, I couldn’t help but to take a quick loop around the galleries of Andrew Wyeth’s work. The Brandywine has the foremost collection of his work and, of course, those paintings still have a palpable magnetism. Though Jamie is undoubtedly a very talented artist in his own right, his paintings lack the immediate spark that Andrew’s can ignite. Jamie Wyeth’s paintings require a longer look, and more space from his father’s paintings than they will ever be given.

Jamie Wyeth’s Solo Exhibition was on view at the Brandywine River Museum of Art through Sunday, April 5, 2015.

Author Rachel Sitkin is an artist, writer, and curator. She recently relocated from Baltimore to Philadelphia, PA.