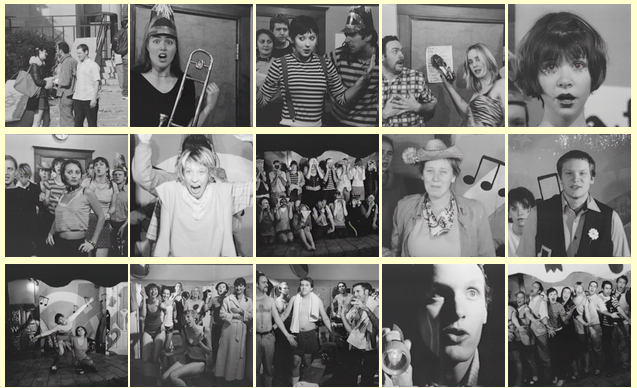

The sneaky smarts of Theresa Columbus’ silliness in Chaza Show Choir

By Bret McCabe

Something strange is afoot in the musical film Chaza Show Choir, and every time you think you have it figured out it molts into something slightly different. It follows a group of high-school singers and musicians in the titular choir who are whisked away to Germany to compete in a tournament, and all along the way some kind of drama ensues. So while the plot sounds straight out of a teen dramedy, putting Chaza in the same category as Glee is like calling the aye-ayes of Madagascar a primate: though technically accurate, in one glance you know the description is wholly insufficient.

The 2003 film was written and co-directed by Theresa Columbus, a Baltimore performance artist who specializes in delivering fun, and her boundless good-cheer powers the entire film. (She co-directed with Didier Leplae, a composer who is one-half of a film composing team.) Chaza is incredibly frivolous, rambunctious, and self-aware, and it’s possible to be carried away by its freewheeling silliness alone. In this cinematic world the line, “Oh my darling love, I’m not a pervy” is a sweet come on. It’s a place where a Step Up-like dance battle takes place between Chaza and a rival team of mermaids. It’s a place where when the class mime is harshly informed, “There is no mime in show choir!,” and she wins them over with a jaunty dance.

That linked scene, however, also spotlights what makes Chaza more than an impish camp exercise. The clip includes an excerpt of an A Chorus Line-like rehearsal scene. Such sequences are familiar tropes in any putting-on-a-show story, and like in the 1970s musical and 1980s film of Chorus the scene is where the performers open up and reveal themselves. In Chaza this scene unfolds with the chorus warming up with a “shame exercise,” where the choir members share embarrassing moments. These range from the comical (falling in front of a theater full of people, who clapped) to the borderline traumatic (falling asleep while masturbating and leaving the bedroom door left ajar). Each shame memory earns a hearty laugh, but the overall tenor of the scene itself provides a window into Chaza‘s anarchic, subversive energy.

Columbus’ plays, performances, and otherwise bubbly spirit has been part of various local festivals, theater productions, and performances for approaching a decade now, and, as with Chaza, the fun that her creations provoke makes it easy to overlook the intelligence behind them. Plus, some of the Columbus performances I’ve seen have tended to be on the shorter side, and Chaza‘s roughly hour-and-a-half running time provides an opportunity to marinate on the way she juxtaposes innocence and experience. Consider the shame exercise: Though played for a knowing giggle, it’s a riff on the rehearsal scene that short circuits the convention of anxiety-riddled performers harboring childhood traumas that have to be overcome so the team can be whipped into shape to create the final polished production. There’s a few layers of parody in each of the giggles it scores.

Chaza Show Choir from Theresa Columbus on Vimeo.

Throughout Chaza Columbus upends such genre conventions and alludes to other musical films outright to toy with their built-in assumptions. Local artist Stephanie Barber appears in the film, credited as a stewardess and the “sexy principal.” She only appears twice as that principal, and in each instance she’s given a “sexy lady” movie entrance: the shot starts at her high-heeled feet and the ogles up her body, the entire camera motion joined by a va-va-voom musical accompaniment. Sending the preposterousness of this blatant cinematic sexism completely over the top, Barber wears as Miss America-style sash that reads “principal.”

What really makes the film an indelible treat is the way Columbus uses the film/musical genre to explore how adults embalm the idea of youth in therapeutic fantasy.

Chaza is a cinematic version of a stage production Columbus created and toured in 1999, meaning it predated some the 2000s examples of this genre (see: High School Musical, the aforementioned Glee, Pitch Perfect, Step Up, etc.), but not previous eras of so-called youth movies and musicals. When the choir members arrive in Germany, they break into a song (sample absurd lyric: “Oh joy, Germany!”). The sequence is riven with the jump cuts, choreographed impudence, and staged wackiness of A Hard Day’s Night in a way that exaggerates how Richard Lester successfully packaged young lads taking the piss out of proper society for mass audiences.

Even better is an early scene that sends up “Summer Nights” from Grease. Chaza‘s musical number cuts between the boys’ and girls’ locker rooms in a song that documents a romantic tryst rather explicitly. But the song’s lyrics are dotted with the vocabulary of health class sex education, and the sheer exuberance the cast brings to this ludicrous song tangles comedy up with uncomfortably awkward voyeurism.

The film is too self aware for such tensions to be incidental; it knows both what it’s lampooning and the medium in which it’s doing it. The movie is shot in grainy, 16-mm black-and-white using available locations and some really low-tech sets. This results in Chaza visually resembling the 1980s films of Richard Kern, even though it traffics in sequences that are part of The Electric Company innocence and part Up with People cult-recruitment creepiness—all of which tapped into some aspect of their era’s youth culture. Throw in the handmade, diorama-like set pieces that note scene changes in Chaza, and throughout Columbus is exploring different ways youth is romanticized in these kinds of productions.

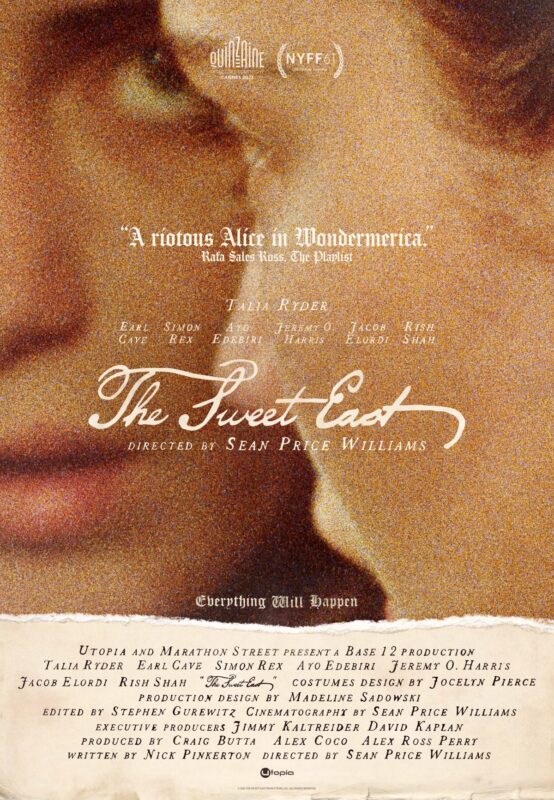

This isn’t the cherished youth that’s mythologized in Wes Anderson’s movies, where an infatuation with precocity is polished into the preciousness of nostalgia. The Oxford English Dictionary defines nostalgia as the “[s]entimental longing for or regretful memory of a period of the past, esp. one in an individual’s own lifetime” (italics its); the science behind the why of nostalgia is still open to debate. I’ d like to propose my own highly unscientific and more than likely specious nostalgia theory: it’s driven by the fear of death. That is, anytime I feel wistful for something in my past—how exciting it was to see a specific band the first time, what an area of town was like when I was younger, how awesome it was when all of these friends were together and that thing happened—I wonder if what I’m longing for isn’t the exact content and context of those events but novelty, experiencing something new to me. And if I’m what I’m craving is newness, is the reason I become more and more distrustful of nostalgia as I get older because with age comes fewer and fewer new experiences? (I also attribute the accumulation of experience with age for the reason why time feels faster with age, but that’s a digression for a different tangent.) Am I apprehensive about a perceived lack of newness because I’m realizing that at some point far too soon the next new experience I’ll encounter is the one I won’t have the chance to reflect upon: the big sleep?

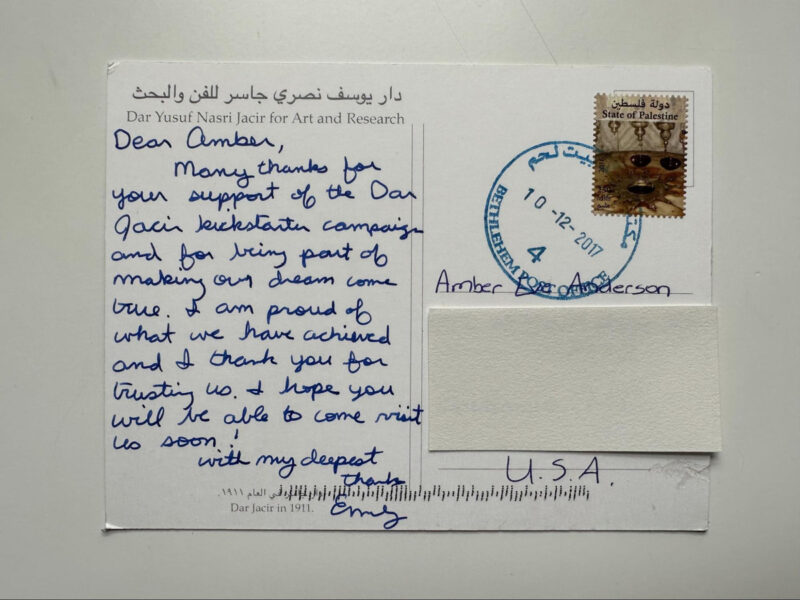

I mention all of this nonsense here because Columbus and Chaza so playfully and effectively skewers the amber cocoon of nostalgia that often fossilizes certain youthful passages—e.g., young love—and instead makes them outrageous. It’s a decision that has the audacity to suggest that what we thought was so special about youth was simply weird and abstruse. And if then was merely odd, not special, might it be possible that everyday life remains just as ordinarily ineffable? That the brain even flirts with such questions makes Chaza Show Choir feel like a form of satire that is impressively anger-free, so much so that by the time the movie reaches its conclusion, in a scene that knowingly winks at Oh, Calcutta, the normalcy of its oddity feels like calm counsel: It’s OK that this doesn’t make sense—what about existence ever does?

Chaza Show Choir screens at the Charles Theater, Wednesday, April 29, at 7 p.m.

Author Author Bret McCabe is a haphazard tweeter, epic-fail blogger, and a Baltimore-based arts and culture writer.