Matthew Moore Explores the Effects of Obsolete Photography, An Interview

By Paul Shortt

Matthew Moore is a photographer who reflects on the disappearance and traces of the past by documenting the present.

This has led to work that explores the landscape of post-socialist empires, the simulation of human experience with animals, and more recently focusing on the medium of photography through the loss of traditional darkrooms. Currently Matthew Moore is an Assistant Professor and Coordinator of the Photography Program at Anne Arundel Community College in Arnold, Maryland. He received a BFA in photography from the College for Creative Studies in Detroit, Michigan and an MFA in 2009 from Georgia State University in Atlanta, Georgia. He has been an Artist In Residence at the Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts in Annapolis, MD for three years. Moore resides in Annapolis with his wife and two children.

Paul Shortt: Your new body of work is a collaboration with Todd Forsgren that explores the loss of traditional photo labs and technology for digital ones. How did this work come about?

Matthew Moore: Todd and I were sharing a studio at Maryland Hall when they abruptly closed their darkroom. It was rather sudden and without warning and because of that, Todd decided to move on. I stayed but moved into a smaller studio. One good thing that came from this is that we got to pick through a lot of stuff that they were throwing out. At the same time people keep calling me at the college and asking if they could donate their darkroom. So I had a plethora of old darkroom equipment, most of which was fairly obsolete. It was a natural reaction to try and repurpose this stuff somehow.

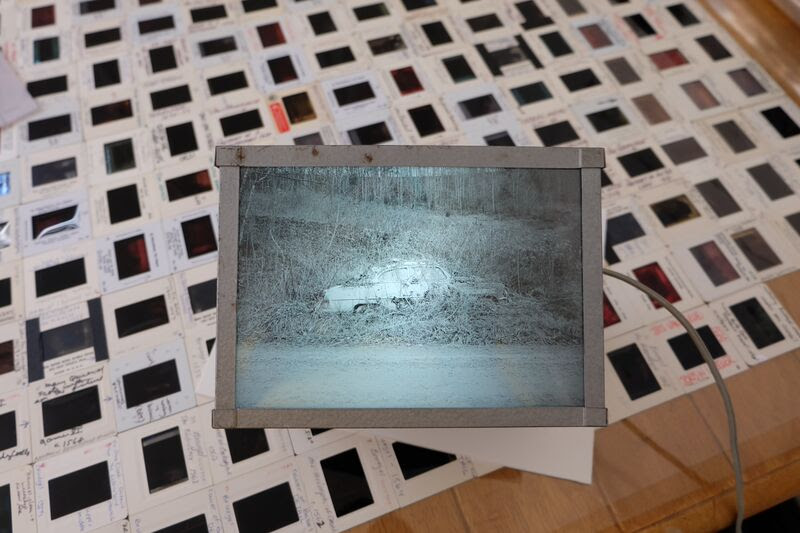

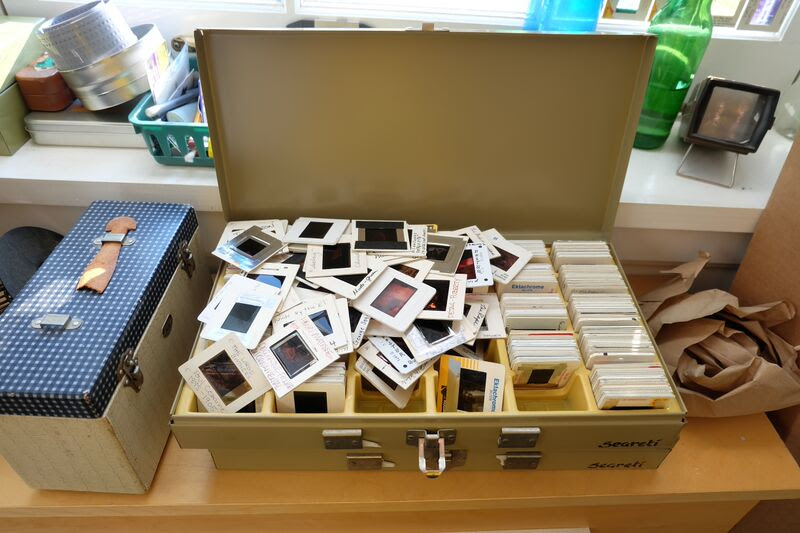

I started by taking tools designed to help people make prints in the darkroom and just inserting them into images. Then I had the idea to make lightboxes out of old safe-lights and enlarger heads. That’s when I realized it could be a serious project. The collaborative piece that Todd and I are doing is called Rose Window. It’s a massive stained glass window made from the old art history slide library from AACC. They got rid of all their slides a few years ago and we took them because we are packrats. When this show came up, we figured it was time to do something with them.

PS: This work is all about finding a function for outdated technology and giving it a new life. Instead of just creating images, you are creating sculptures and functional objects. Is this a new way of working for you?

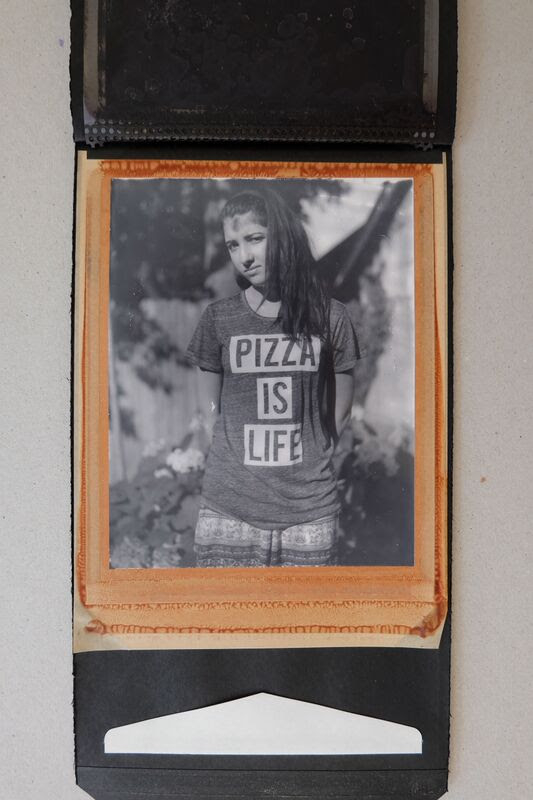

MM: Yes, totally. I’m focusing much more on the method of presentation and on the process of making the images, rather than the content of the images. For example, one of the things I discovered in a donation was an unopened packet of Type 55 polaroid film. It was expired in the 70’s but they don’t make this stuff anymore and a lot of people really miss it. I put my sister up against the fence and shot some portraits of her on a sunny day. I can’t tell you how enjoyable it was to peel open that polaroid for the first time. It’s something that I’ve done many times but the last time was probably 10 – 15 years ago. Some of the film didn’t work but a few of them did. I’m going to hang the entire thing right on the wall, so you can see the chemical smears and everything. The portrait is nice but the object itself is what’s really important to me.

PS: When and where will this work be presented?

MM: It opens on September 10th in the Martino Gallery at Maryland Hall. I can’t think of a better place for a show about the loss of darkrooms than place that just got rid of their darkroom.

PS: How does this body of work connect with your teaching?

MM: That’s a great question. I teach both analog and digital photography and I’m always trying to get photography students to engage with both. To look at the two ways of working sort of like tools in a toolbag. One day you use one, but on other occasions you may use the other. The works in this show are very nostalgic for the analog, but they are in no way sad for it’s loss. In fact I think the works in this show present the loss of these tools as a necessary step in the evolution of photography.

For example, it makes perfect sense to me that people are no longer using gray cards to meter photographs. By putting these tools on an alter hopefully we will get people thinking not only about where photography has been, but also where it is going.

PS: Has change always played a key part of your artwork?

MM: I’m interested in the idea of disappearance. All of my work is about that in a sense. One could even argue that all photography is about that. In my photographs I try to record the present, while also making reference to the past and the future. I’m very interested in the question of how the landscape records and reveals history. The East-West project, and my latest project, Post-Socialist Landscapes, both address this question. Both of these projects are shot in former communist countries but they are not about communism, or even politics. They are more about how different societies manipulate their environment as a way of changing the past.

Some countries are very aggressive about covering up the past, while others don’t mind having reminders around. If the government comes in and builds a parking lot over the place where a statue of Lenin once stood, is there not still some trace of Lenin? Certainly some people walk by that spot and remember his presence. My photos are in search of that presence.

PS: Animals have also played a key part of some of your previous work. In If Animals Could Talk you address the viewer gazing at animals, while in Exodus you capture images of animals using a motion sensitive camera. Connection and disconnection with animals seems to play a key part of both these works. Can you talk a bit about what led you to these projects?

MM: I keep coming back to the topic of animals. I feel like our relationship with animals and the natural world is disappearing because it is becoming simulated. I was very influenced by John Berger and the essay he wrote on looking at animals. He presented the idea that if you see a tiger in the zoo, you’re not really seeing at a tiger. You’re looking at a tiger that has become de-sensitized to human eye contact. It would be a very different scenario if you saw a tiger in the wild.

That’s the basis for this work; how we as humans are coming into contact with animals. In the zoo it’s all fabricated, with cinematic lighting and big panes of glass – because they realized the bars were making people depressed. And the other way most people experience wildlife is in their own backyards. Those projects are my way of recontextualizing those experiences. Or in a sense, re-simulating them.

PS: The Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts seems to be a vital resource for artists in Annapolis. Can you talk about your experience as an artist in residence there?

MM: It’s been a good experience overall. And yes, they are very important to Annapolis. For one thing, the galleries are really nice. I’ve gotten great support from the gallery director there, Sigrid Trumpy. They also provide the only legitimate AIR program in the area. Annapolis, not surprisingly, has a very traditional art scene. There are a lot of sailboat paintings and stuff like that. And Maryland Hall caters to that somewhat. But I also get the sense they are trying to be more progressive.

PS: You work a lot in the Czech Republic, where your wife is from. What is the art scene like there?

MM: There are a lot of great things happening there. It reminds me a little of my home town of Detroit. They make great use of abandoned industrial spaces. Last summer I had a show there in an abandoned Jewish cemetery. That was creepy but awesome. I’m not a big fan of the Prague gallery scene though. It can be very inclusive and cliquey. I do however like some of the public art that is happening in Prague. I feel like that culture really needs to be forced out of their comfort zone sometimes and much of the public art taking place in Prague does that.

*****

Analogous: Experiments Within the Void Between Digital and Analog Photography at Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts

September 10, 2015 to October 27, 2015

Martino Gallery, 2nd floor: Photographic work by Todd Forsgren and Maryland Hall Artist-in-Residence Matt Moore.

Gallery Reception & AIR Open Studios: Thursday, September 17 | 5:30 – 7 pm

More information here.

Author Paul Shortt is a visual artist, writer and arts administrator. He received his MFA in New Media Art from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and his BFA in Painting from the Kansas City Art Institute. He is currently the Registry Coordinator and Program Assistant at Maryland Art Place and lives in Washington, DC.

Photo Credits: Todd Forsgren (portrait), Paul Shortt, and Matthew Moore