On the BMA’s Imagining Home by Bret McCabe

The most interesting aspect of the Baltimore Museum of Art’s ambitious, if problematic, exhibition, Imagining Home, is a series of three short videos called “Home Stories.” For this project, 11 households lived with an artwork from the BMA’s collection for about a month, and afterward were interviewed on camera about the experience.

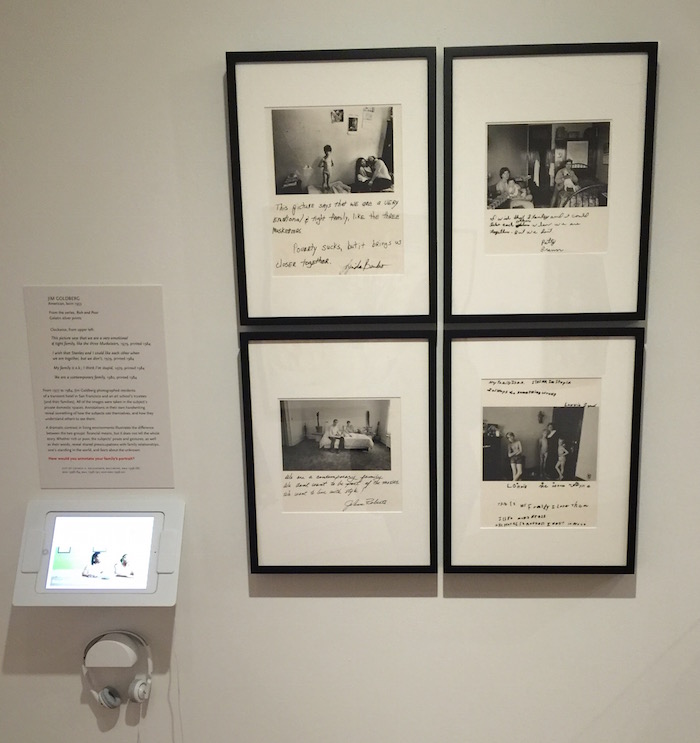

The households range in race/ethnicity, age, city neighborhood, and the art works—the shower curtain included in The Thing Quarterly, Issue 16, featuring text by human branding opportunity Dave Eggers; a set of four annotated photographs from Jim Goldberg‘s “Rich and Poor” series; Alfred Stieglitz’s photograph “The Steerage”; Walter Henry Williams’ painting “A Quick Nap”—are included in Home. Mounted just beneath the works is a small tablet screen with the short videos.

Even in brief interviews the responses to the works is casually profound. Three different households lived with the Goldberg “Rich and Poor” photo series: a white woman, two African-American women, and a single African-American mother with three kids. One of the two African-American women says she was initially disappointed that all four photos featured white people, as she wondered how they were going to work in their household. She immediately adds that through reading the accompanying text she was able to think about the images as being part of an ongoing conversation about poverty. The single mother says she connected with the single mother featured in one of the photos; her son remarks that he wonders why the people in the photos have such little stuff, and wants to know what happened to them to make them this way.

This video, and Goldberg’s series, is the only explicit comment about economics that Home makes. The rest of the exhibition, however, takes place in a more implicit economic construct: that of the retail marketplace. Home looks and feels like a showroom, and the relationship to the included art works it cultivates is one of ownership: How would you feel with this piece in your house?

Now, I’ll fully confess that Home‘s retail mood rubs me the wrong way; what I’ve yet to figure out is a reasonable argument for why. Home is the inaugural exhibition in the BMA’s new Patricia and Mark Joseph Education Center, so the mission of the space itself is an educational one aimed at an audience of school children and to rethink how art can exhibited for such purposes.

Home, which will remain up for three years, features more than 30 works that come from a wide array of the BMA’s permanent collection—decorative arts, paintings, photography, sculptures, textiles, and works on paper from around the world—collaboratively curated by Gamynne Guillotte, the BMA’s Director of Interpretation and Public Engagement, and Oliver Shell, the Associate Curator of European Painting and Sculpture. They divided the works into three sub-categories—Façades and Thresholds, Domestic Interiors, Arrivals and Departures—and grouped the works accordingly. The Goldberg photo series is hung in the Domestic Interiors section, along with Carolyn Brady’s “Letters from Home (Via Reginalis)” painting, a circa 1932 “Toastmaster” toaster, and Pierre Bonnard’s “Luncheon Table” painting.

Carolyn Brady’s Letters from Home

Carolyn Brady’s Letters from Home

As a museum experience, it’s pretty sly: you come across pieces removed from their typical art-historical and/or geographical groupings. As a human experience, it’s all too familiar. The Patricia and Mark Joseph Education Center is a series of lovely galleries/rooms just off the museum’s east entrance by the museum shop and Gertrude’s; walking in, it kinda feels like those Ikea showrooms where there’s a little examples from everywhere else in the store—or from every other collection in the museum—that you can sample before heading to the rest of the big box store, er, museum.

Yes, the Home gallery feels like it’s trying to recreate the retail experience. In a recessed seating area along one wall is an iPad tablet, where museumgoers can respond to the question, What is “home” to you? Responses—on a recent Saturday, they ranged from “where my dog is” and “being curled up in bed with my love” to “cookies baking and delicious smells” and “my mother’s quilts”—are projected onto the floor in a floating series of user-generated “home” thoughts.

These sentence fragments are actual responses to a question posed by the exhibit. The very last item on the wall text for every piece is another question, posed to spark reflection. With Ben Marcin’s photograph of a solitary rowhome titled “Baltimore, MD” the question is, “How is your neighborhood changing?” With Laurie Simmons’ photo “Walking Home” is, “What roles do you play in your home?” With Brady’s painting, “What might we learn from looking at your table?” With a pair of tea bowls, “What do you offer visitors in your home?” With a high-backed seat from Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, or Ghana, “What is the shape of your favorite chair?”

With the swirling home thought projections and so many questions about how I felt about stuff, strolling through Home made me feel like I had wandered into Fight Club‘s Ikea catalog hallucination, and the exhibition was about to ask me, “What type of dining set defines me as a person?”

Laurie Simmons “Walking Home” 1989

Laurie Simmons “Walking Home” 1989

I’m admittedly being a bit glib here, but this impression was one I couldn’t get past every time I spend time in Home. The included questions overwhelmingly focus my attention to art objects as one of material possessions: How do I feel about this this thing I own? Now, it’s possible that such an attitude is an effective one for getting younger people/students to think/talk about art and objects, a colloquially direct way to get them to think about what stuff can mean. And if so, bravo.

What I can’t shake about the retail experience of the show, though, is how it assumes a visitor has a home and the disposable income to populate it with stuff. For a show revolving around the idea of “home” in Baltimore, it has to operate as if the city isn’t in the midst of a housing crisis, where, as the Housing Policy Watch blog noted last year, “it’s becoming increasingly difficult for middle-income renters to find housing that’s both safe and affordable.”

This is a city where, from 2008 to 2010, 14,635 foreclosures filings were filed, where foreclosure.com currently lists more than 1,000 foreclosed homes for sale, where housing discrimination is a huge factor in manufacturing and sustaining the city’s socioeconomic disparities. Baltimore is a city where, according to the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance Vital Signs 13 report (PDF) “between 2009-2013, 52.8% of the households that pay rent spent more than 30% of their total household income on housing-related expenses.”

For far too many city residents, the idea of a home that is a safe, comfortable, and welcoming space that you would want to decorate with objects of personal meaning, and have the means to do so, exists only in the imagination.

Marian April Glebes. Three Sheds for Three Sites, Shed I: Home Shed

Marian April Glebes. Three Sheds for Three Sites, Shed I: Home Shed

All of which makes Marian April Glebes‘ Imagining Home-accompanying project such a welcome inclusion. The local mixed-media artist partnered with the nonprofit architecture salvage organization Loading Dock to create “‘Three Sheds for Three Sites, Shed I: Home Shed,” a sculptural installation that puts a number of items used for domestic activities—cooking, cleaning, sleeping, etc.—onto a series of three connected cabinets on wheels. You imagine the piece could be packed up and taken anywhere and, through audience participation, turn any space into a performance of some domestic activity. Anywhere could be home.

Spend a bit more time with the piece, however, and a different performance idea comes to mind. Maybe because I moved over the summer and had the headache of downsizing and packing fresh in the memory, but the way Glebes ingeniously packs a small apartment’s worth of necessities onto this piece brought to mind the thought process that accompanies being a serial renter in the 21st century, the material culture triage that takes place when moving into progressively smaller and more expensive spaces.

“Home Shed” is parenthetically titled “(One is at the Museum and Performs the Functions of Home, One is at the Salvage Material Re-Use Center and Performs the Functions of the Museum, One is at the Home of the Artist and performs the Functions of a Collection).” That descriptor cheekily alludes to the fact that this collection of movable domestic items means that anybody’s assortment of said items placed into a space performs the function of “home”—the museum, the apartment you were last in, the apartment you’re currently in, the apartment you move into next.

Of course, a performance of “home” isn’t the same as having one, but that’s what makes Glebes work here so poignant: home can remain an out-of-reach ideal even when you’re paying rent. This sense of home being a source and symbol of anything other than comfort and joy is what’s missing from Imagining Home: it assumes this ideal home is the same for all people.

I’m going to be a bit unfair here and bring up two pieces of music instead of visual art. The song “Home! Sweet Home” was originally penned in 1823 by American dramatist John Howard Payne in London for an opera (English composer Henry Bishop provided the melody). It became a beloved American folk song, such that during the Civil War the Union army anecdotally banned its bands from playing it for fear it would cause men to desert from homesickness. The song itself is a nostalgic piece of gooey sentimentality—it’s the one that goes “Be it ever so humble/ There’s no place like home”—but it struck a popular nerve.

In 1919, roughly a century later, Clarence Williams and Charles Warfield wrote another “home” song that became a popular standard, this one a blues song. Bessie Smith’s 1923 version of “Baby Won’t You Please Come Home” became the yardstick by which every other cover/interpretation was measured. It’s a lonely holler of a song wherein the female narrator calls our for the man who ain’t there, and for two verses she asks for him to return with the titular refrain. It’s not until the third verse that she gets down to brass tax: “Landlord gettin’ worse/ I’ve got to move May the first/Baby won’t you please come home/ I need money.”

In roughly a hundred years the subject of a popular home song moves from its idealized sweetness to something that could be taken away by a property owner. What’s our relationship to the idea of home today? That’s a question that Imagining Home the exhibit, and the works included in it, seems to circle but never comes out and says out loud—save for Glebes’ works. Perhaps it’s a question the exhibit will begin to explore more diligently over the exhibition’s three-year run. I certainly hope so, because right now the idea of home as imagined by Imaging Home is static, differing chiefly by the things people can buy to fill it.