Wilderness and Household at Current Space

By Ani Bradberry

Upon entry into Current Space, visitors were greeted by the whir of two absurd appliances: a hand-made freezer containing a raw porterhouse steak and a pair of adjacent box fans, one functioning as a wind turbine to stimulate a magnetic generator which then powers a small car fan attached to a plywood stand. The effect of both of these contraptions was a slightly uncomfortable yet humorous dizziness as familiar appliances became objects of industrial nonsense.

Wilderness and Household is an apt title for the ongoing collaborative project of husband and wife duo Yhelena Hall and Michael Henri Hall. Claiming to conceptually amalgamate industrialized space and the domestic routine (the two central factors of “western” life according to their artist statement), the show visualized the couples’ interpretation of modern daily life as something intimately bound to manufacturing, and therefore completely absurd.

To accomplish such criticism, the artists explore several conceptual methods through sculpture: collage, decay and reassignment of an anticipated function of an object. In doing so, the artists inject suspicion into the viewers’ consideration of everyday materials and appliances. The symbolic works in Wilderness and Household range from kinetic mechanical sculpture to wall-mounted pieces, all appearing to be structurally in flux. The series itself is an ongoing work in progress where each piece seems to be in a state of deterioration, whether physically or functionally or both.

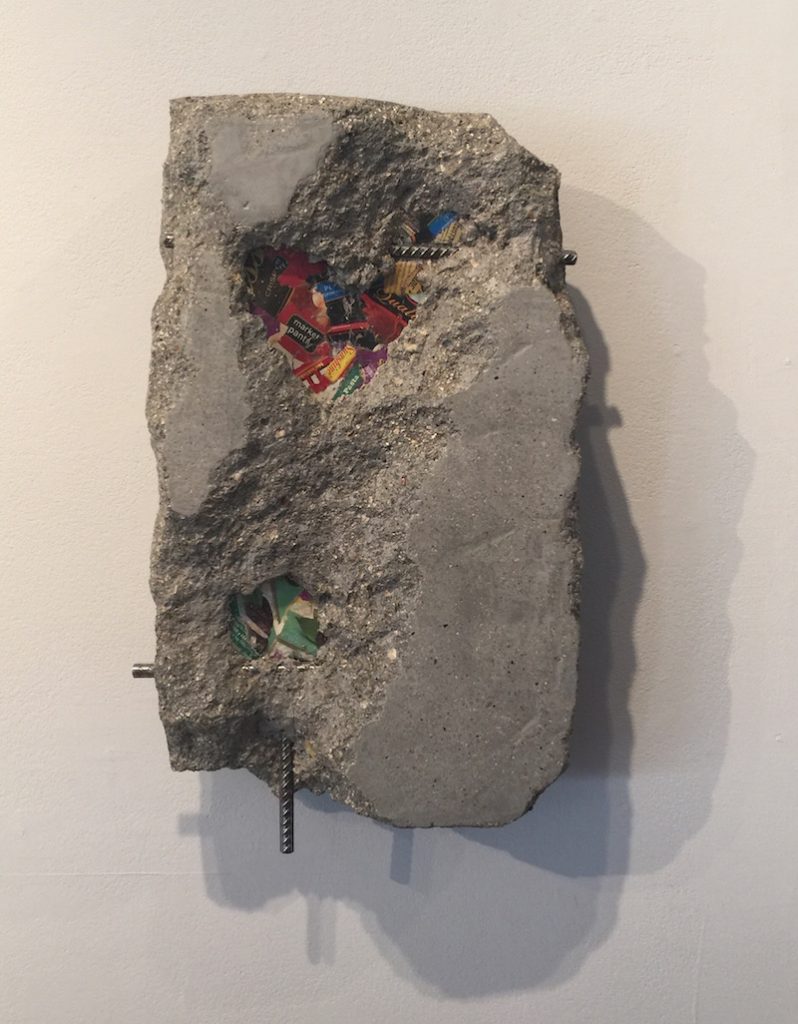

The artists materially and conceptually blur distinction between domestic and industrial, symbolized most explicitly in a series of “concrete collages.” These pieces are cast from the crumbling viaducts of Chicago’s urban landscape, fabricated in the studio with embedded colorful product packaging and polished rebar, then re-installed permanently onto the walls they were casted from. Reflexive in their message, the collages literally embed waste culture into urban fabric. In this exhibition, however, the cast sculptures are installed directly onto the gallery wall without photographs of the installation in Chicago, which unfortunately reduces the architectural power of the pieces.

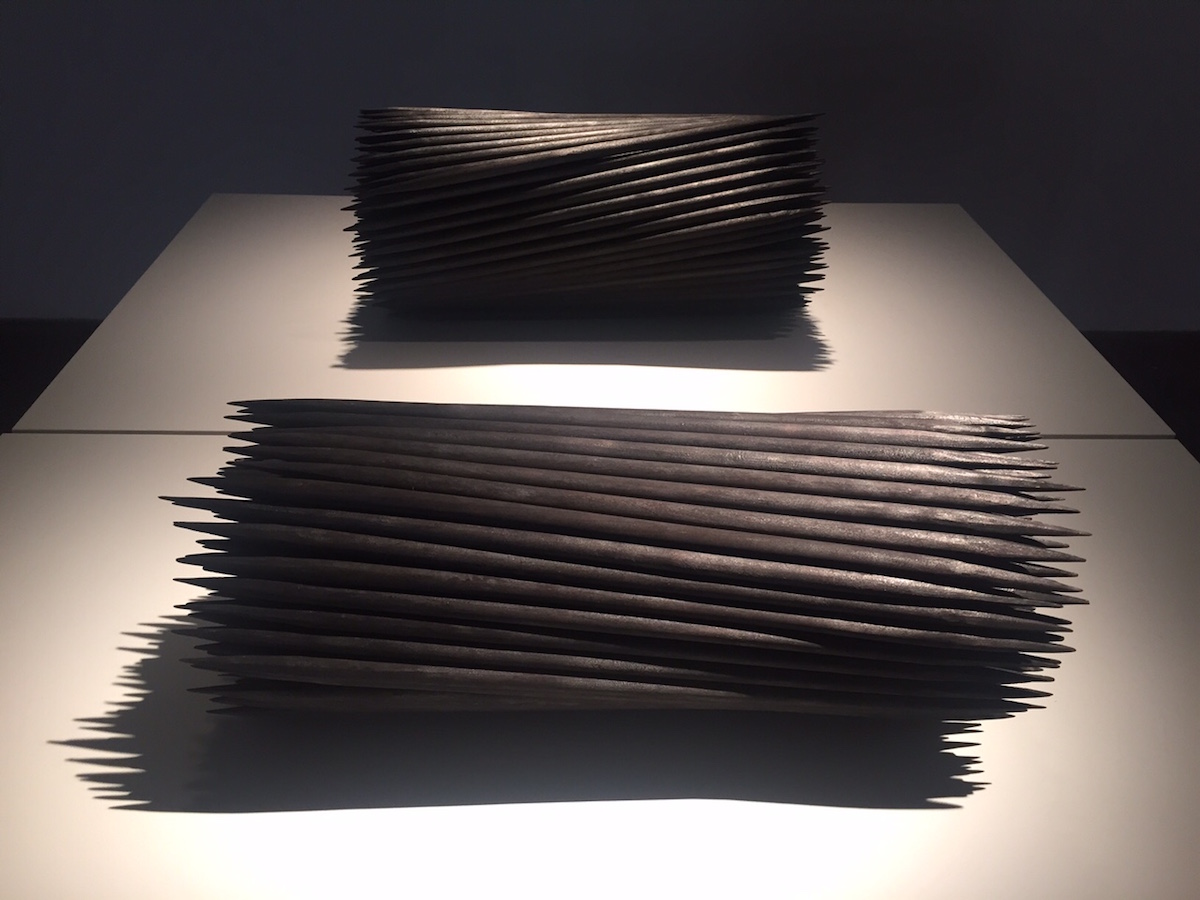

The two freestanding rectangular concrete works are more nuanced: one is a horizontal brick with two rebar “arms” outstretched and the other a vertical piece that reveals skeletal rebar that seems to be pulled away from the concrete. The state of warped erosion in the heavy materials appear both random and decisive, suggesting careful consideration by the artists’ during the process of construction.

Consequently, each of the sculptures can be read as a performative action against the constricting landscape of post-industrial landscape. Challenging the rigid functionality of design and manufacturing standards that have developed with the rise of mass industry, the artists create frustrating objects that resemble Alexander Brener and Barbara Schurz’s ‘anti-technologies of resistance’ in order to defy oppressive urban structure.

Returning to the title offers other explanations of the artists’ criticisms depending on visitors’ definitions of the subjects. “Wilderness” and “Household” are simultaneously complementary and conflicting, both hinting at chaos but in different states of regulation. A “Household” in relation to “Wilderness” suggests containment, taming, domestication, while “Wilderness” remains in a constant state of growth and decay. Considering the use and mockery of home appliances in this exhibition, the title calls attention to the theater of domesticity, offering a kind of cathartic opportunity for laughter in the face of a crumbling post-industrial urban landscape. Perhaps this moment of humor is the victory of “Wilderness” over “Household” as the rebar sprouts from concrete.

As a collection, these sculptures are united in their corrosion of ideology, revealing the foundation and skeleton of consumption within humanity’s reliance on electricity and mass-production. However, it remains unclear exactly whose interest is in question.

If the artists are implying that we, as contemporary “westerners” are living within structures built upon on our own consumed garbage, why is there no investigation of who manufactured them? While these pieces alone function as objects of resistance, there is a disappointing lack of pointed symbolic criticism. A decidedly non-global or the self-described “western” perspective seems to miss the point of rejecting the unsustainable societal and architectural structures linked to domestic norms, especially when raising concern for the infrastructure of industrialization as a whole. Ignoring the overseas factory worker or farmer in an exhibition that aims to alert Americans of their dependence on cheap food and appliances seems counter-productive.

Nonetheless, each work in Wilderness and Household was smartly and radically fabricated. According to their website, this series is an ongoing work in progress and I am optimistic to see its progression.

*****

Author Anahita (Ani) Bradberry is an artist and art historian based in the Washington DC area. She earned undergraduate and graduate degrees in modern and contemporary art from American University’s feminist art history program. After completing her MA, she focused on her own artistic process through participatory light installation and neon sculpture that can be viewed at Transformer in DC. Walking the line between artist and critical art writer, Ani is interested in engaging the public through radical creativity. You can follow her on Instagram @aniberry.

E13: Discourse, the 13th year of Transformer‘s annual Exercises for Emerging Artists Program engages DC based emerging art writers Eames Armstrong, Ikram Lakhdhar, Christine Bang, Ani Bradberry & Martina Dodd, in facilitating & promoting community exchange through critical arts dialogue.