One Thursday Night in the Capital of Magical Realism by Michael Anthony Farley

Depending on who you ask, and what arbitrarily-drawn boundaries are used, Mexico City is the most populated urban area in the Western Hemisphere. It’s remarkable, then, that I almost never feel stressed out or rushed here.

There are, however, three notable exceptions. One is when I’m trying to squeeze into infamously over-packed metro cars in the morning crush. Or when foreigners say “Mexico is the new Berlin” and I feel like I have to frantically enjoy it while it lasts, before AirBnB’s and pied-a-terres ruin this place. Mostly, that #FOMO manifests when I plan to cram-in too many cultural activities.

There are so many museums across the metropolis that if you tried to visit one a day, it would literally take nearly half a year to see them all. On any given night I’m torn between, at a minimum, half a dozen appealing events—from openings and screenings to workshops and feminist dance parties—usually scattered between two or three vast delegaciones.

This is the account of one such Thursday-night-in-the-life of CDMX.

It’s about two P.M. when the messages start coming in, asking what the evening’s plans are. I spend almost an hour chain-smoking on my terrace with my laptop and phone, bouncing between Facebook and texts and email and Google Maps, outlining an itinerary of openings and the most logical order to see them based on geography and public transportation lines.

Two promising shows—in Coyoacán and San Rafael, respectively—don’t make the cut because they’re just outside the densest cluster of activities. I can walk to the gallery/artist residency chlORO in Roma Sur from my apartment in Doctores. If I arrive there exactly at 7, I’ll have plenty of time to take one of two bus rapid transit routes to Colonia Juárez and catch an opening at Iniciativa Curatorial MARSO. From there, it’s a straight shot on Metro line 1 to Chapultepec, followed by a not-so-unpleasant brisk walk across the massive park to Museo Tamayo, where a painting biennial is opening.

I can end the evening at Anonymous Gallery, also located off of Metro line 7, where an event starts at 11 P.M. and ends at 4 A.M. (I’ve been told an installation has transformed the gallery into a conceptual discotheque with can’t-miss late-night programming throughout the month.) I’m giddy with a sense of accomplishment over how uncharacteristically well-planned and selectively curated my night is going to be.

But by the time I walk over to chlORO (having been distracted by an Occupy-style anti-gentrification protest en route and losing 15 precious minutes) my friends outside are already telling me the lines for the Bienal Tamayo will be prohibitively long if I don’t leave immediately. I send an apologetic text to the people I told to meet me at MARSO and dash into chlORO, where my buddy from Los Angeles Marcel Alcalá is having a solo show, Faith in Conquest.

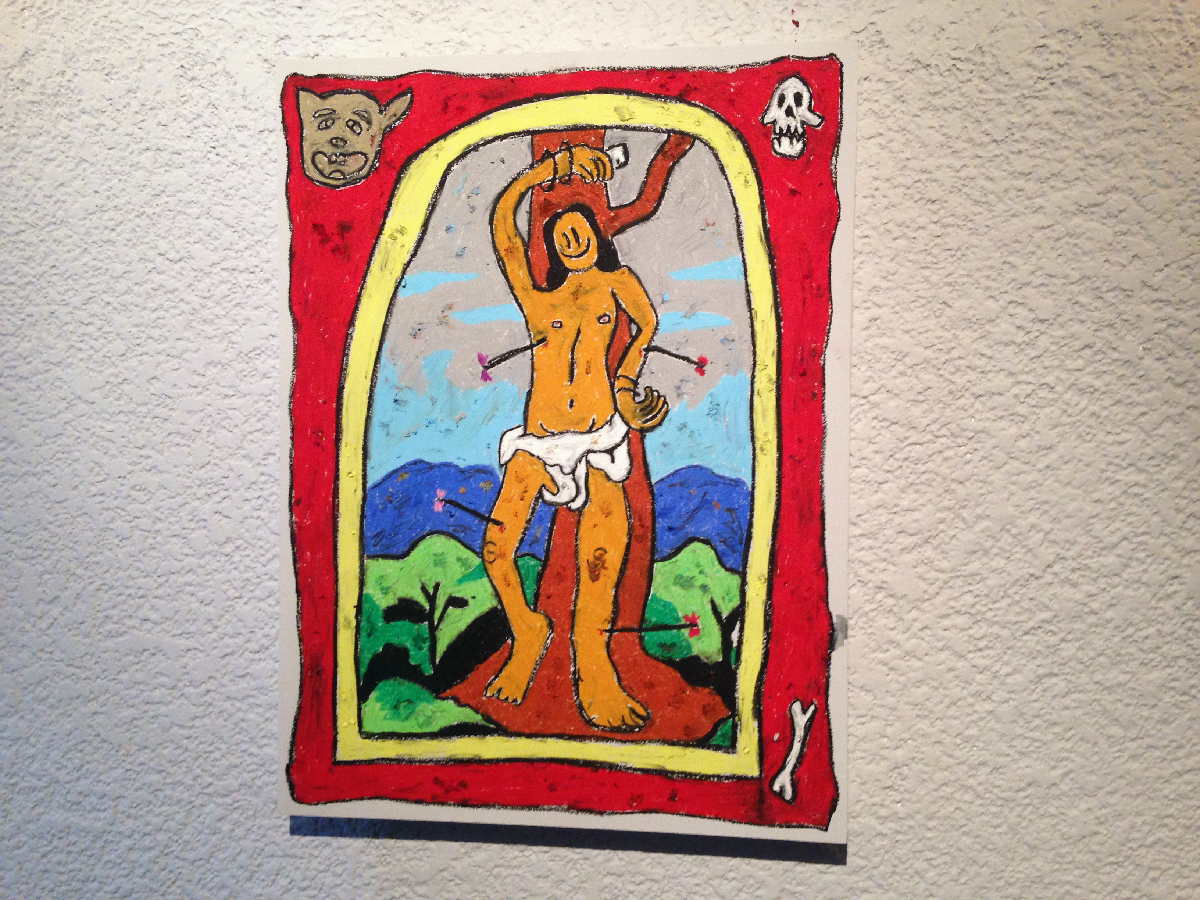

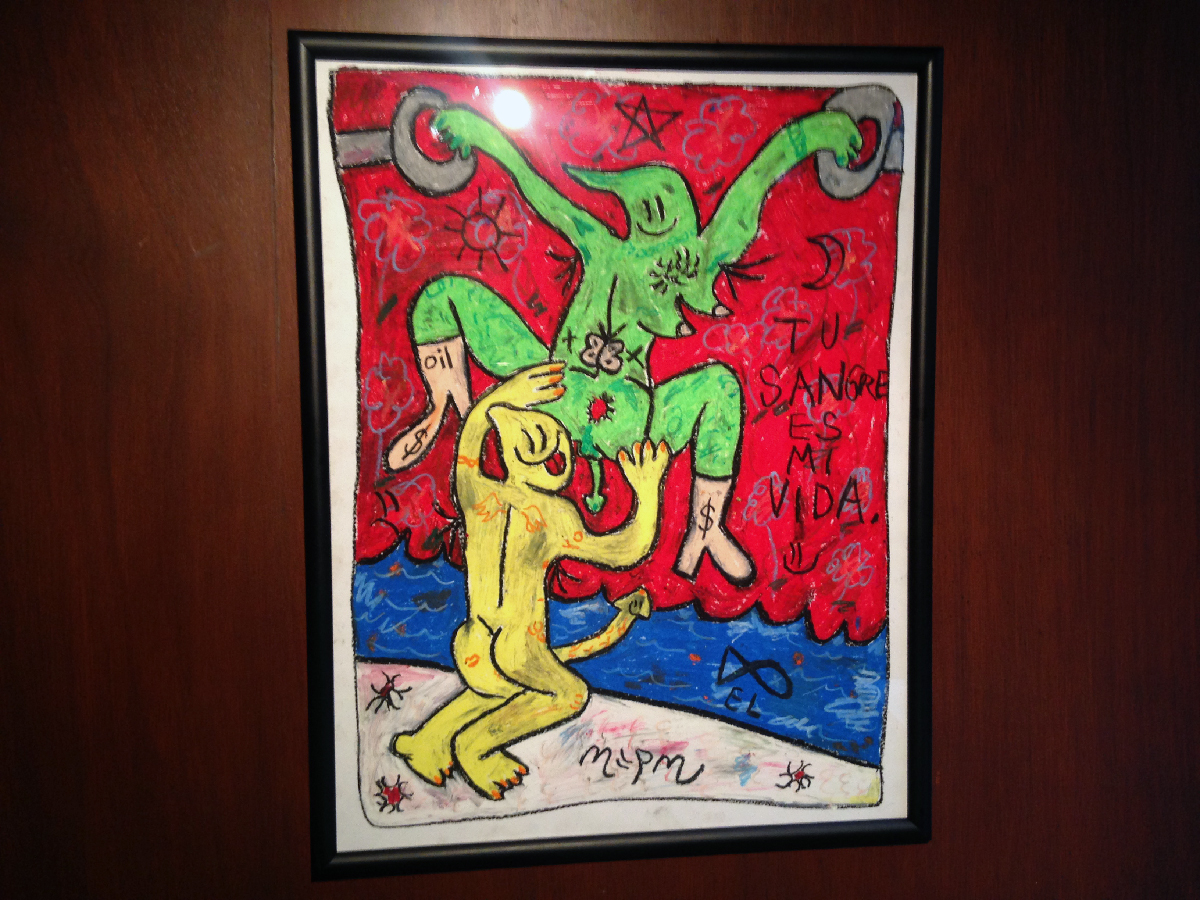

Marcel’s work is great. Shortly before our respective departures from L.A. for CDMX, I wrote about his endearingly awkward pastel caricatures navigating sexuality and identity in late capitalist dystopia. Here, those ambiguous bodies are subjected to the legacy of colonialism and religion—posing in sexualized tableaus loaded with references to Catholic art history while Pre-Columbian figures look on with vaguely horrified gazes.

In “Ella”, a nun poses for a “sexy” selfie in a graffitied bathroom, lifting up her habit to reveal high heels, while an Olmec statue lurks in the corner, grimacing. “St. Sebastian Selfie” is exactly what it sounds like. The famously homoerotic icon of martyrdom is viewed smiling, smartphone in hand, through a mirror flanked by laughing masks that respectively appear to depict Xolotl and Mictlantecuhtli—two Aztec gods associated with death.

The sense of irreverent humor and semiotic remixing in Marcel’s work gets at the heart of what I love about the Mexican approach to identity politics. Here, the vast majority of the population have inherited genes and/or cultural patrimony from both colonizers and the colonized (something most Americans either don’t have to reconcile or don’t).

There’s a sense of mischief prevalent in the art/activism scenes here that work at unpacking/subverting all the heavy baggage that comes with Mexico’s violent history and the legacy of Catholicism’s rigid gender roles and unending guilt-tripping. I’m often reminded of the Emma Goldman quote, “If there won’t be dancing at the revolution, I’m not coming.”

I remember there won’t be wine at the museum if I don’t get going, and have to recalculate my navigation plans. I hop on a bouncy electric trolebús that cuts diagonally through Roma Norte to the Bermuda-Triangle-like bus hub at Chapultepec. Rather than figure out the next transfer, I ford the rain-soaked streets and parks on foot to the Museo Tamayo. Predictably, when I arrive muddy at the entrance, my friends (and most attendees) are queued-up outside at the bar.

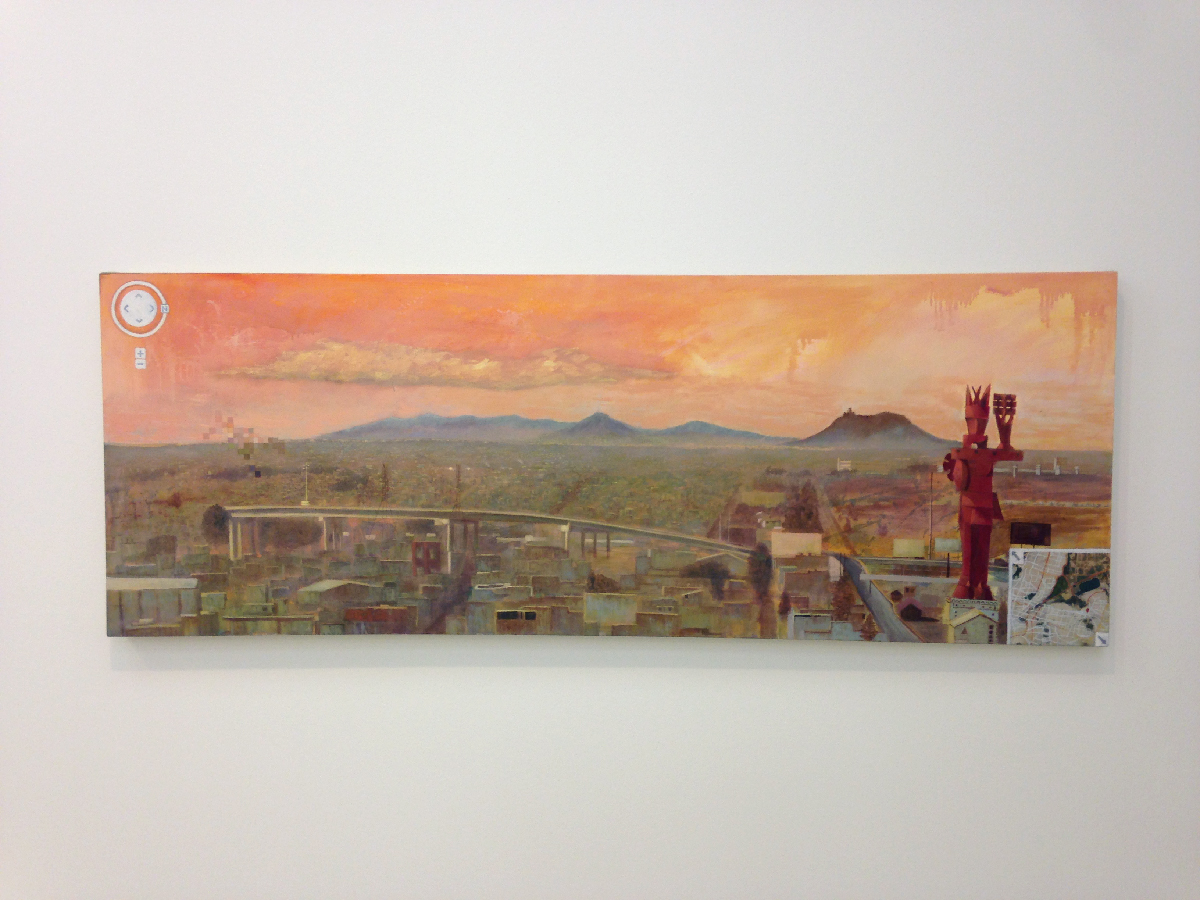

Stano Cerny “Diosa de Los Nopales”

Stano Cerny “Diosa de Los Nopales”

I can only describe entering the Bienal Tamayo—a much-hyped juried survey/competition of Mexican painters—as a bit of a perplexing let-down. It’s probably the least “contemporary” looking biennial I’ve ever seen, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but I can’t shake the impression that most of the paintings here look dated and derivative.

Half of the work feels like a homework assignment to make something inspired by figurative painting of the 20th Century. Surrealism and allusions to early modern masters dominate. Some works are literally grouped based on purely aesthetic decisions like similar color palettes. It’s a curatorial strategy that does no favors to anyone involved. For a survey show of mostly-representational painting in 2017, the majority of the work is shockingly apolitical.

Gustavo Villegas’ “How to Make a Bomb”

Gustavo Villegas’ “How to Make a Bomb”

There are notable exceptions. Gustavo Villegas’ “How to Make a Bomb” explodes across 13 panels—one of the sole pieces to break out of a single rectilinear canvas—depicting explosions in Middle Eastern cities. One panel bears solely the text “Cerca de 130,000,000 resultados.”, implying that the imagery was sourced from Google. Villegas’ fluid handling of paint is masterful up-close. There’s a real luminescence to his depictions of blasts that’s gorgeous. I feel slightly guilty admiring his renderings of flames knowing what the source material is.

Margarita Adalid’s “Soldados”

Margarita Adalid’s “Soldados”

There’s a complimentary unease—somewhere between empathy and morbid curiosity—in Margarita Adalid’s “Soldados”. The tableau depicts a waiting room full of U.S. soldiers, presumably in an airport, departing to/returning from a conflict abroad. Yet notably absent in the Bienal Tamayo are references to domestic politics. Given the socio-economic turbulence of the past year, I find that problematic, and wonder if that’s symptomatic of the museum’s relationship to the state or the proclivities of the jurors.

When I bring this up to one of my companions, a local gallerist, she shrugs. It’s troubling, but we agree good painting doesn’t have to serve a political end. She also offers a more positive outlook on the dated vibe of the show: surely the curators must’ve been attempting to demonstrate the influence of Mexico’s art-historical bigwigs, including Rufino Tamayo, on living artists. I look to the next gallery, which holds paintings by the artist for whom the museum was named, and see her point. From a distance, it looks like a continuation of the biennial.

My opinion of the show softens slightly, but I can’t shake the feeling that this survey of living Mexican painters doesn’t do justice to the vibrant and boundary-pushing art scene I’ve fallen in love with. And Mexico’s 20th Century representational painting always owed a substantial chunk of its weight to Marxist/anti-colonialist concerns that are all but absent in the safe work here. (Still, there are highlights. More images at the end of the post).

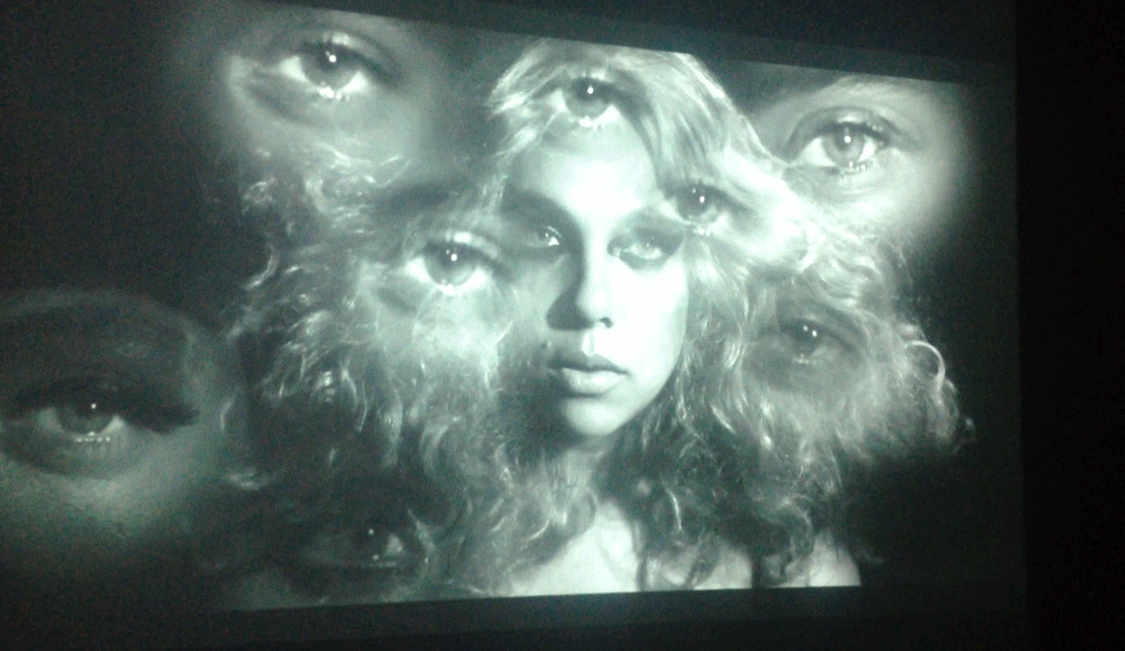

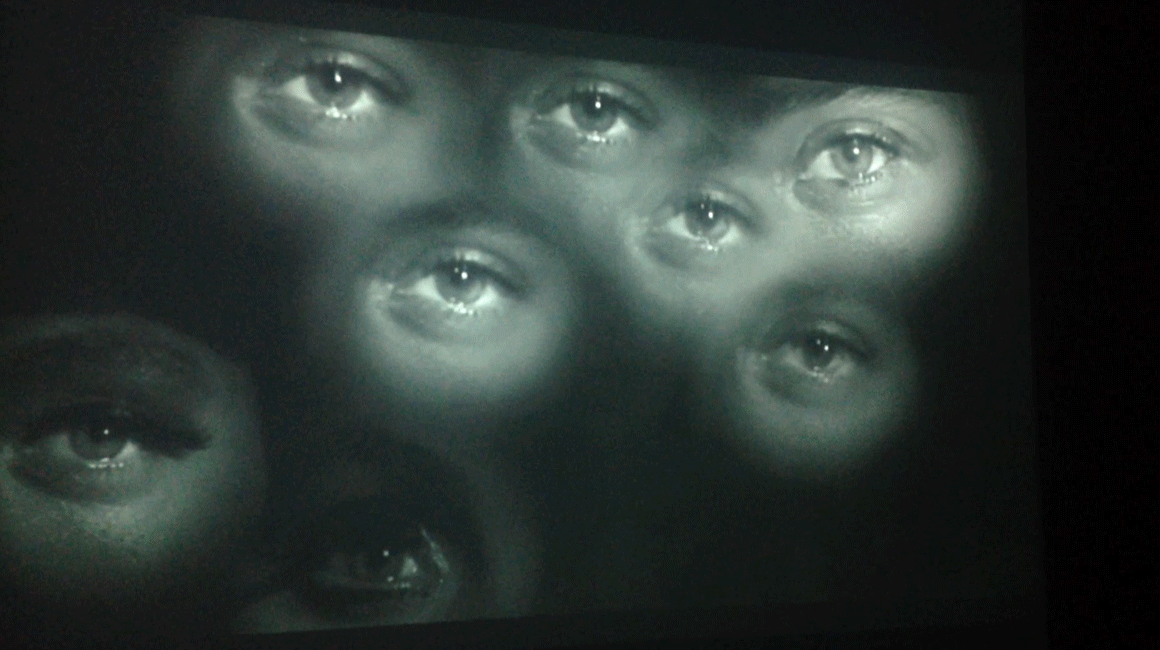

Orly Anan’s “Ellas”

I’m regretting that I prioritized the Bienal over MARSO, but my friend convinces me to make another detour. We Uber back to Roma for the opening of a group show at Licenciado, Resistencias. The show—with an international lineup including artists from Colombia, Cuba, and Mexico—is also pretty uneven. The gallery’s domestic-like layout, however, guarantees that the good work has plenty of distance from the more commercial schlock.

Orly Anan’s mini solo show Sobre el aire compartido totally steals the spotlight here. Her installation “Ellas” begins in one darkened room, where a video projection of a woman (presumably the artist) alternates between creepy/glamorous looks, surrounded by eyes. It makes me realize Cindy Sherman’s “film stills” would be better off not-so-still—even in a crowded opening it was oddly hypnotic.

The next room holds a series of vacuum-wrapped wigs and women’s shoes, suggesting different identities that can be opened and tried on. I’m reminded of Joss Whedon’s dystopian cult TV show Dollhouse. Like Anan’s video, it speaks to glamour to be consumed but also something unsettling.

The implied interactivity of the sealed dress-up components is carried through to the final chamber, which basically functions as a giant selfie-machine. The room holds a series of mirrored vitrines, “Altar I, II, and III”, each with a nearly-symmetrical array of knick-knacks. Some of the objects allude to health and the body, others are just weird.

I’ve barely had time to take in the show—and catch up with an old friend from MICA I run into at the opening—when my group is yet again getting restless. The gallery has run out of mezcal, apparently, and we end up taking a much needed pit stop for tacos and drinks at nearby Pulqueria Los Insurgentes, one of the best watering holes for people watching and conversation. I’m introduced to a Costa Rican artist, Fabiola Carranza, who’s translating the work of David Wojnarowicz to Spanish. I can’t wait to read it.

By this point it’s nearly midnight, so we decide to share a cab to Anonymous Gallery. It’s located on the fringe of Nuevo Polanco, a district of hyper-gentrification (and private museums) so intense it can feel like the set for a cyberpunk satire about capitalism’s excesses. Getting to the neighborhood by freeway always feels a little surreal—gliding among futuristic cantilevered highrises above the rapidly-disappearing old stucco homes and taquerias that’ve somehow held out—so I’m in a weird headspace when we arrive. The installation, by Radamés Juni Figueroa, also has a place/non-place vibe that plays with a similar ambiguity between authenticity and artifice, culture and commerce.

Radamés Juni Figueroa

Radamés Juni Figueroa

For starters, we have to wait in an inexplicable line to get in. My gallerist buddy giddily suggests that it must be part of the artwork (Figueroa’s makeover of the hangar-like space pays homage to salsa clubs and discotheques of the 1970s).

But then we have to shell over 100 pesos to enter (only about 5 US dollars, but way more than cover at most Mexico City clubs). Following this, my Mexican friends are shocked that drinks at the bar are fully twice the price you’d expect at local DIY spaces. The party is starting to feel less like a conceptual artwork and more like a gallery running an overpriced after-hours spot for foreigners with ironic haircuts and favorable currency exchange rates. The “Mexico is the new Berlin” panic starts to set in when I realize the majority of the conversations in the room are in English or French. Am I part of the problem? Fuck.

None of my friends planned to need this much cash, so we decide to head to an ATM. The twink working the door dismissively tells us we can’t leave and re-enter, offering no explanation as to why. I zone out while my companions argue with him for about 20 minutes, and realize it’s one of the first experiences I’ve had in Mexico where someone has been honest-to-god rude in a nightlife/art context. The Berlinification (or perhaps more accurately Barcelonafication) has entered the terminal stage.

We’re given a 30 minute window (a hard-negotiated compromise) to find an ATM and return. This would normally not be a problem, but since it’s after midnight in dead-at-night Nuevo Polanco the suspense starts building—nearly every ATM is located inside shuttered luxury malls or looming corporate compounds. Finally, we find one in an eerily-empty upscale 24 hour supermarket (which has an entire aisle devoted to hundreds of varieties of olive oil). On the walk back, I mention that this is one of many nights where Mexico City lives up to its reputation as a capital of Magical Realism.

We’re all laughing about this as we duck across a freeway overpass and stumble across a tiny shrine to Virgin Mary, left somehow unscathed by all the incongruous condo/shopping center construction around her. We’re all ex-Catholics, so we say a tongue-in-cheek prayer for the night to get better.

Evidently, she interceded.

When we arrive back at the party, the music is great and the bartenders appear to be too stoned to remember to take our money. I run into no fewer than four people from Baltimore—a friend from my teenage years’ sister who is now a DJ here, an acquaintance from MICA, and two artists visiting for a work trip. One of them hands me a cup of punch-soaked fruit. About 30 minutes later, someone tells me it’s laced with MDMA.

At one point in the night I realize I’m alternately sloppy making-out with someone I haven’t seen since art school to club music and sucking club drugs out of a soggy orange in a sweaty former auto body shop. The bar has run out of any appealing mixers, so I’m drinking vodka and Diet Coke. Some nights in Mexico might start out seeming dangerously like Berlin, but end up feeling an awful lot like college in Baltimore.

Additional Favorites from the evening:

Author: Michael Anthony Farley is Senior Editor at Art F City. From 2008 to 2011, he was a founding member and visual arts director of the Baltimore nonprofit arts space The Annex Theater. Since leaving that position to attend graduate school, his criticism has been featured in a number of publications, he has served as a curator for Miami’s Zones Art Fair, and his work has been exhibited internationally.