Cities, Memories, and the Experimental Films of Margaret Rorison

Editor’s Note: This profile was originally released in the BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas: Issue 06

All city landscapes tell stories, and Baltimore’s is making filmmaker Margaret Rorison anxious. Capitalism’s rapacity is remaking her hometown through the Trojan Horse of development, erasing entire neighborhoods in the process. She’s both curious about and skeptical of the nostalgia for the past that’s being bulldozed. And she’s worried that this rapid change is turning social awareness into tourism-friendly public relations, which sidetracks the political will required to build a more equitable future.

She’s all these tensions at once, evident in the thirty-something artist’s different practices. In Rorison’s indelible short films and experimental collaborations she explores ideas about contemporary anomie and urban life, while in the monthly Sight Unseen film series she curates at the Parkway Theatre, she spotlights the wide range of ideas coursing through experimental cinema.

And right now, her work zeroes in on Baltimore’s accelerating gentrification. “What happened after the Uprising felt like a silence being broken, trying to come together and work together against segregation,” Rorison says, adding that, in the three years since, local leadership seems more concerned about the barriers to continued economic development than the city’s history of exclusions and economic disinvestment that created the conditions the led to the Uprising in the first place.

Such policies create and sustain the selective affordability that produces entities like arts districts. “In an underground scene where things aren’t too expensive, people work together with the resources that they have and a lot of magic and genuine energy can come out of it,” Rorison continues. “After the Uprising I felt there was a shift, especially in the arts community, where people were trying to work together more. Now, I feel like that could be lost, that the communities that need attention aren’t getting it, and that Baltimore is seen as hip and cheap. And I think about the evolution of the city. Now, you can live anywhere—what does that do to the idea of a city?”

Like poetry, experimental film/video is an intimate media where the political is the personal is the metaphysical, articulated through idiosyncratic vocabularies that deliver an intoxicating poignancy. In works such as Memory of August, a six-minute black-and-white cinematic portrait of her grandmother, or Der Spaziergang, a three-minute cinematic collage of walking around Berlin, Rorison layers footage to create a palpable sense of a person and a place. Experimental film’s emotive possibilities allow Rorison to explore her subjects through the imagery and ideas to which she’s long been attracted: landscape, memory, and language.

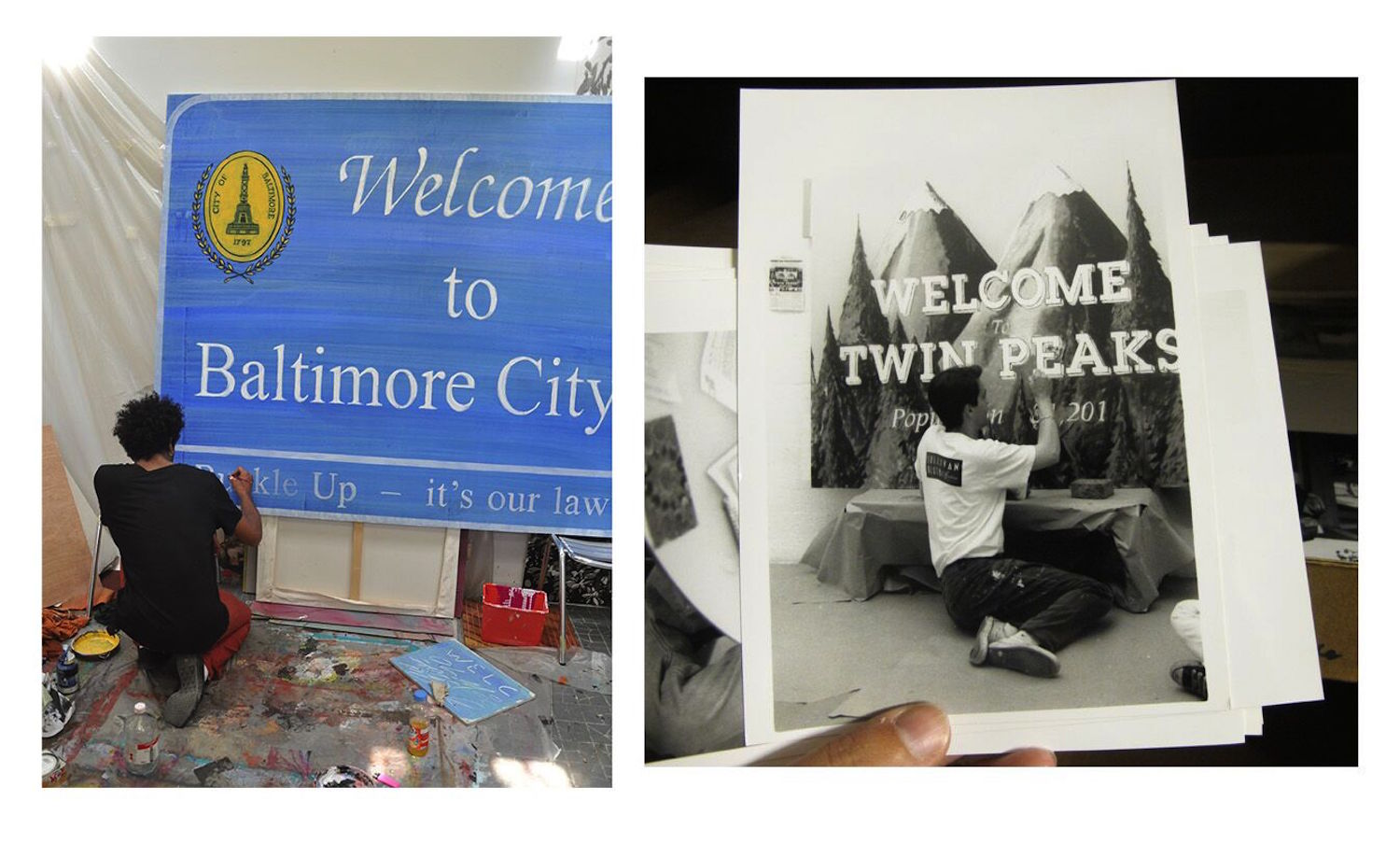

Her current project, Restoration of a Memory, is her most first color film in four years and explores Baltimore’s architecture and landscape. “Baltimore is changing and a lot of beautiful buildings are being demolished,” Rorison says. She mentions an old church on Fulton Avenue she would often pass in West Baltimore. The building’s roof had caved in, there was a bus stop out front, and neighborhood people would wait for public transportation back-grounded by the house of worship’s ghost. Visually, “it was an intense shot,” Rorison says. She planned to film it, but when she went back, the church was demolished.

She realizes she’s treading in potentially dodgy terrain of visually romanticizing urban blight. “I don’t want to film decay and I don’t want to be a voyeur,” she says, and brings up the landscape paintings of Richard Diebenkorn as a point of reference. She mentions how in her filming of the city—such as Reservoir Hill homes, a former creamery in East Baltimore that’s being converted into lofts, the longest unbroken chain of rowhouses on Wilkins Avenue—she’s been focusing on architectural texture, color, and form, noticing urban landscape’s layers. She’s drawn to the tensions, juxtapositions, and contradictions found when ordinary actions and events—waiting for a bus, street advertising, new development—is overlaid on the architectural past.

Rorison touches on ideas similar to what visual theorist Griselda Pollock explores in her “The Homeland of Pictures” essay about the role of place and memory in Van Gogh’s paintings. In that piece, Pollock notes a conventional art history narrative that landscape evolves over the 19th century as the first generation of artists move from country to cities, confronting questions of not just what to paint but where. Countryside nostalgia might echo sentiments for lost childhood in such landscapes but artists like Van Gogh also began injecting psychological subjectivity into landscape, turning it into a creative space to negotiate how the self fits into place.

Echoing Pollock, Rorison notes that contemporary artists navigating that self-and-place negotiation are confronting a burdened history. Urban landscapes are reminders of the previous occupants, evidence of past lives, and are reservoirs of other people’s memories. Using urban landscape as a cinematic subject necessarily involves respecting those past lives and memories.

“Memory is so powerful and also selective,” Rorison says, adding that as a filmmaker she’s invested in the stories already in a place instead of trying to orchestrate a narrative as a director. Stories already exist in the world, and she’s trying to tap into those non-narrative emotional experiences.

“I feel like it would be very difficult for me to write a convincing fictional piece,” she says. “I love learning about the history of people and place, and I feel like it’s easier for me to work with history or memory, something or somebody that’s emotive about a personal story. There’s a lot of creative freedom to work inside that. Working off of life is more natural for me.”

Photos by Rachel Rock at The Parkway Theater.