DC-Based Artist Brian Dailey Confronts the Overlaps Between Art and Politics With a Career in Government and International Negotiations by Juliana Biondo

Brian Dailey’s artistic trajectory is as fascinating as it is curious. He started out not unlike many artists, with an MFA earned in 1975 from Otis Art Institute and then several years as a practicing artist in Los Angeles. However, his career took an intriguing turn when he decided to pursue a PhD in the fields of diplomatic history and weapons politics, completed at the University of Southern California in 1987.

Dailey went on to work in the Pentagon’s office of chemical warfare negotiations, to teach as an Adjunct Professor of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School, then work as a Professional Staff Member of Senate Armed Services Committee. He then served as Executive Secretary of the National Space Council in the White House before moving to the private sector as a Senior Vice President and Corporate Officer of Lockheed Martin.

“Many people tell me that I should have stayed in art,” says Dailey. “Yet what I observed and learned during this experience was unique, especially for an artist. I saw geopolitics from the inside and experienced it on the playing field. I consider that period, in arms control, in the government, even in the corporate world, my greatest performance piece.”

In 2008, Dailey made an equally radical decision: he returned to his artistic practice, actively leveraging what he gained from his study into international affairs to inform his creative practice. Now, a decade later the artist works in film, media, painting, installation, and photography, weaving together narratives of his individual experiences with investigations into the construction of national and supranational identities. As an artist, Dailey gives us a window into how the power of the visual arts can be harnessed to understand the more nuanced facets of tectonic shifts in global power dynamics, making his work as timely as ever.

Currently touring his latest and ever-growing body of work, “WORDS,” which features a video piece capturing individuals from all over the world reacting, in single words, to thirteen different concepts (ie. democracy, happiness, capitalism, etc.) – and showing his piece “Lamentations” – a sculpture which meditates on nuclear theology and its implications in our atomic age – in the Foggy Bottom Biennial. Dailey is between international trips and sat down to share more on his artistic upbringing, his inclination for the political, and his lived experiences in over one hundred countries.

WORDS

WORDS

Where did this intensity came from, to work as an artist at this time?

I found what I wanted to do in life. Art is my passion, my religion so to speak. I consider museums to be my church, my temple, my mosque – I am at home there. The creative process is what fuels my curiosity. It takes me from curiosity to explorer to discoverer. In the end, discovery is what makes me happy in life.

When did your interest in international relations arrive? I know one of your first major series after you graduated started to explore politics.

It’s a good question. My parents divorced when I was three years old. My mother took my sister and me back to New Zealand, which was her home. In those days, you had to travel the ocean by island hopping, which sometimes meant ships and prop planes. Things didn’t work out for her in New Zealand, due to family issues. Being from a British Commonwealth country, she decided to take us to England. I found that while you travel at that young age you’re not cognizant of every detail or at least you don’t remember it. That said, I believe that experience permeates you. I think that is what innately inspired my passion for global issues.

In my youth, I loved geography, looking at globes, and reading about foreign places. When I was fifteen and deciding whether to become a photographer, I also considered joining the Peace Corps. So that was my early crossroads in life: photography or Peace Corps. While I was eager to explore the world, I decided to pursue photography, which ultimately lead to other forms of visual arts.

What about the politics in your work?

My early work quickly incorporated contemporary political and social issues. For example, works such as the 1975 installation, “Closely Watched,” focused on U.S. government surveillance of American citizens. To some extent, I believe the catalyst for this direction or theme came from my concomitant travel to Europe while in art school. Every monetary scholarship I received went to pay for trips to Europe to see museums and attend the Venice Biennale.

During these trips, I also visited East Berlin and Poland. I became intrigued by the communist system. Later in 1976, I took the Trans-Siberian Express from Helsinki to Japan where I hoped to study with the film maker Akira Kurosawa. That travel across the Soviet Union resulted in meeting artists and writers that were all exiled to Siberia. We talked about artistic freedom and politics. These fascinating people were terribly mistreated. That inspired me to give a lot of thought to the question of artistic freedom and government control.

How did that line of inquiry evolve?

With that as background, I started to study arms control and nuclear weapons. At that time, the tensions were high between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Things looked dangerous with the competitive global dynamics of the Cold War. At the same time, So often I was sitting around the table with other artists in L.A., having a drink and talking about the global conspiracy of the Council of Foreign Relations, the Trilateral Commission, and the “Seven Sisters” oil companies – and I wondered whether I could ever get inside the “conspiracy,” to penetrate it and find out if there was in fact one.

It was my excessive curiosity that took me in that direction. Maybe I shouldn’t have taken this diversion. Many people tell me that I should have stayed in art. Yet what I observed and learned during this experience was unique, especially for an artist. I saw geopolitics from the inside and experienced it on the playing field. I consider that period, in arms control, in the government, even in the corporate world, my greatest performance piece.

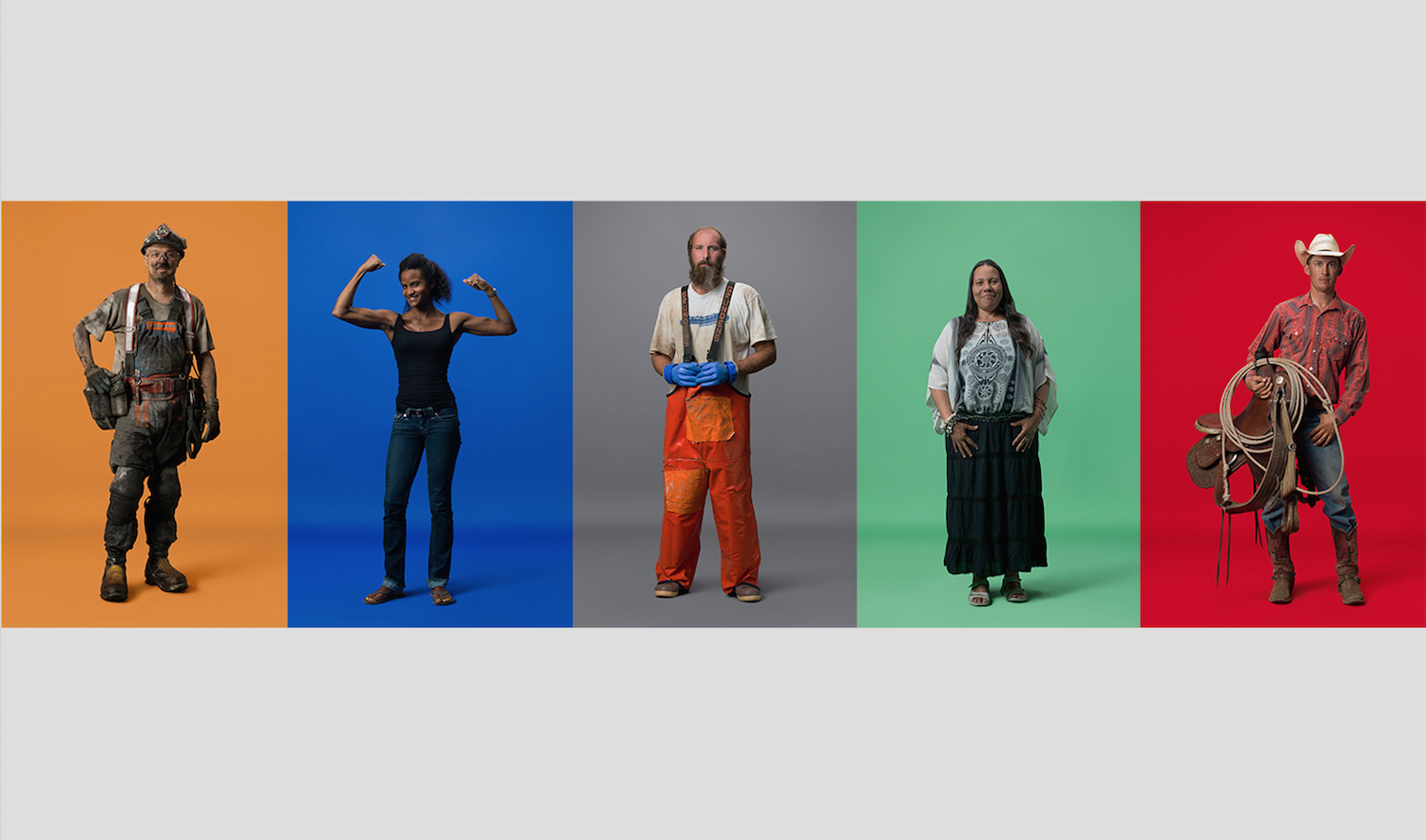

America in Color

America in Color

After you made this shift did you miss art making? How did you deal with that?

Yes, I did. But at the same time, I found that coming up with solutions to enhance stability and peace required creative thinking, which I believe my art training provided me. In the end, that is what made me successful in international relations and even business. I do regret that I didn’t take photos of or document the many unique situations I found myself in. I was involved in some fascinating and important inside historic events. I was the proverbial fly on the wall. But in the end a camera would be unacceptable for people in these situations. If only I had a cell phone camera at that time.

Is there any one moment that sticks in your mind as a particular instance that you wished you would have photographed?

My extensive travels through the Soviet Union and Russia are the times I most regret not having had a camera to document those experiences. With the more than fifty trips to Russia, I saw many breathtaking things during a time of great upheaval and change. At Lockheed, for example, I was hired to run their Russian cooperation programs or joint ventures, which the U.S. government encouraged them to pursue. The concern, of course, with the end of the Soviet Union they would sell the nuclear or chemical technology to rogue countries or regimes.

By engaging business relationships with their aerospace industries, we hoped to head off such transfers of technology or people. Thus, these many trips I took during my government and private sector career allowed me the opportunity to see formerly secret cities and facilities as well as witness such historic moments during the transition of Russia from a communist system to a democracy, not to mention the bringing down of the Berlin Wall. In the 1990s, Russia was taking on the character and dynamics of the “wild west”. It was both fascinating and dangerous.

I am curious to hear more about your insight because I think it was you who said – it was in your bio –that “international affairs and visual art are seemingly diametrically opposed professional fields.” Seemingly is the key word here. Do you feel like that “seemingly” came out after your experience in government, or did you feel like going into your experiences with government you were thinking they were already connected as professional fields?

No, I thought they were completely different.

Did you really? You didn’t expect to see connection points?

No – but I did think that I had to satisfy my curiosity about who and what ran the world.

So your decision to go into government wasn’t an artistically driven decision, it was a curiosity one. And then you were able to connect it back?

Yes. But, I always knew that I would go back into art.

There was no doubt?

No doubt. When the Cold War ended in 1991, my intention was to return to art. But I didn’t want to return without resources. So that’s when I decided to take up the offer from Lockheed to manage their Russian joint ventures. Doing this for a few years would generate enough resources to allow me to return to art without ever having to worry about making a sale or having a second or third job, like I did when I started in art.

When I was looking at your work – those from before your time in government and those after – I see some connections, but I also see differences. What I saw is a kind of shift from a focus on the larger-than-life systems that impose onto the individual, but then in pieces like “WORDS” it becomes more about the individuals, and how they project out what they want. Do you agree with that?

Your point about “WORDS” is important. My current work is centered around people; and the different faces of people, their different cultures, their different languages. I have long been passionate about domestic and global diversity, a direction first reflected in “America in Color,” which was on view in the Stephan Stoyanov gallery in New York in 2012.

After that exhibition, I went on a trip around the world, and I thought about what would be interesting to take on as my next art endeavor. That’s when I decided to embark on the “WORDS” project, which has been ongoing now for over the last six years and traveling across more than 100 countries. The question I asked in starting that project was: how has globalization affected language and culture? But in making this a video project, I didn’t want it to be about people discussing their thoughts on War, Peace, Government, etc., in an interview format. In other words, I didn’t want long detailed answers. I was trying to draw out an emotive imagery by asking them to respond to the thirteen different nouns with a single word. In short, capture their emotion associated with that word.

Many people in the art world believe that all art is political. I disagree. I believe art is basically autobiographical. For some, that means making a compelling beautiful work whether it be abstract or representational. I like to make work pulled from experiences, from our discoveries but most importantly, focus it about an issue of our time – usually social or political. I guess you could say I am more conceptual than process or media driven.

Switching gears a bit – do you have any favorite contemporary artists working on similar ideas?

Rather than comment on any particular living artist, I would prefer to address what I find exciting in contemporary artistic practice. The history of art is also the history of technology. In that context, much of the work of greatest interest to me is being done with new technologies that have provided new vehicles enabling artists to experiment creatively in innovative ways. Just as the advent of oil paints in tubes or photography freed up artists to explore new dimensions in painting, portraiture, and art making in general, new technologies have opened up new paths for artistic activities.

We see today remarkable art being done in video, artificial intelligence, social media, digital photographic processes, virtual reality, to name a few. I find this exciting. Adding to the effect of the rapid pace of technology and society in general is the fact that the artist today does not necessarily need to be limited to a certain genre of work explored to the nth degree. Artists today have so many tools with which to express themselves that they are not shackled to one medium for most of their career. It is an exciting period.

Do you have a favorite non-living artist?

Francisco Goya would have to be at the top of my list. Without a doubt, he is one of the great political artists. Painters back then played a role similar to that of photographers today as documentarians. They were court painters who documented royalty or some form of the government. But Goya was one of those artist who, on the side, explored many very interesting aspects of his time. I am thinking about series such as The Disasters of War, The Caprices, and the Black Paintings. These works are powerful, meaningful, and an inspiration.

Do you feel that art is at its most powerful when it is revealing something about humanity? Or, about the underbelly of humanity?

I do. But the irony is that I don’t think most people like looking at art of their moment or certainly not political art. What I was told very early on was disheartening: don’t do any political work because it’s not going to get a lot of buyers. I think this is truer in the United States than in Europe. That said, in the last few years, I’ve seen many more emerging artists taking on social and political themes in their work. It is both promising and refreshing.

Polemos

Polemos

I have a question specific to your piece, “Polemos.” How did you write the script for that?

I hear many people tell me that they are tolerant, and/or that they don’t like intolerance. Yet, we can’t seem to find a way to get everyone to sit around a table and have a basic conversation. The Polemos video, completed in 2012, was inspired by this challenge and how to address it. At the time, Occupy Wall Street was an emerging movement and the Tea Party was becoming a powerful political force. Yet few people, if any, were talking across these political barriers. Many said they wanted to; but then they were just yelling and screaming at each other. The same could be said of the traditional political parties.

I wanted to do a piece that explored this timely issue. I went to the websites and copied writings that captured basic ideas of the Democrats, Republicans, Tea Party prescribers, and the Occupy Wall Street movement. I put that into a script titled “Polemos,” an ancient Greek work for “war-cry”. I wanted to portray this crescendo of people starting to listen, intending to listen, but then deteriorating into unconstrained debate with nobody listening. In the end, they walk away effectively not hearing a word of each other’s point of view.

I hired four actors to participate. After learning which viewpoint most closely aligned with their own, I assigned them each instead a script taking the opposite position. The woman who said she leaned Republican was given the part of the Democrat. The woman who identified with the Occupy Wall Street movement was asked to represent the Tea Party role. They were thus moving out of their bubble and act an opposing part. At the end, what was interesting is that they all said they learned a lot about the various points of view.

That said, an intrinsic aspect of the work was the cacophony of opinions. As you are watching it, you are getting angry and frustrated, you are becoming impatient…This is a key aspect of my installation and performance work – get the viewer really engaged and make them think and participant in the work.

Where can people see your work now, and what is next for you?

In Washington, DC, I encourage your readers to visit the Foggy Bottom Biennial which runs until October 28. In the Biennial is a sculpture work from a recent series called Lamentations. If readers are interested they can find out more about this series by reading my interview about the works in “Project Muse” by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Upcoming exhibitions of the “Words” project and other works will be first shown at the Baahng Gallery in New York City in November of 2018 and two exhibitions of “Words” and other works will open in January at the Schlesinger Art Center and the Visual Arts Gallery in Alexandria. More information on those exhibitions are available on my website. For the more adventurous folks I have an exhibition of “Words” in Kampala, Uganda opening this Spring at the Makerere University Art Galllery.

Portrait of the Artist

Portrait of the Artist

Links:

Lamentations Interview by Project Muse Link

In downtown Chicago at “One Dearborn” you can view the American in Color series which is on exhibition until October 19, 2019.

To find out more on Dailey’s works, and upcoming tour locations for “WORDS” visit his website.