Smokey the Bear—the stoic-faced, brown-eyed, shovel-bearing icon of fire safety—features as an unexpected introduction to Animal Tales, an exhibition of illustrated manuscripts dating between the 13th and 17th centuries that opened this May at the Walters Art Museum.

“It seemed silly at first,” says Dr. Lynley Herbert, Assistant Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts. “It seemed like it wouldn’t necessarily connect, but I did a tour of the show last week for a group of young teenagers. And I walked in and pointed at him and said, ‘Does anyone know who this is?’ Everyone knew it.”

People of all generations, at least in this country, recognize the image and what it signifies. “Everyone here knows what Smokey the Bear stands for, and I bet there’s another popular animal like him in other cultures that everyone can identify visually and associate with morally,” adds Nicole Berlin, co-curator and Zanvyl Krieger Curatorial Fellow at the museum. I find myself thinking of the various wise animals populating the folk tales of my childhood in India—the Panchatantra, dating to a Sanskrit-speaking subcontinent in 200 BCE, and the Jataka tales, Buddhist fables from the third century, both of which thrive in oral and visual storytelling traditions to the present day. It seems to be a common thing across cultures, the tendency to attribute similar kinds of intelligence to animals based on their behavior. A crow is clever, and an owl is wise, but a fox is always either shrewd or cunning. Snakes? Duplicitous. Monkeys? Mischievous. Lions? Kingly, imperious, noble. The animal mascots of our contemporary times carry that trend forward—a furry or feathery friend that represents the values of a brand, but is also often viewed as a personality to imbibe and learn from.

Nicole Berlin and Dr. Lynley Herbert, curators of Animal Tales (Photo by Priyanka Kumar)

“The way people read images is fascinating,” Berlin continues. “We do it in the present day with emojis, for instance. We do it all day! You look at this image and know what it means because you’re of a certain generation, or you’re born or live in a certain place where it means something specific. Images are part of cultures everywhere, and people understand them in certain ways based on cultural knowledge.” In the context of Animal Tales, Smokey the Bear suddenly seems like the perfect headway into understanding animals and their connection to symbolism in earlier times, thematically connecting past and present. It might be surprising that an example like this can encapsulate very complicated ideas about visual literacy and what a timeless phenomenon it is, but wouldn’t you rather have a bear than Barthes telling it to you?

For an exhibition that is relatively small—12 manuscripts presented in a dimly lit room in simple, elegant, climate-controlled cases—Animal Tales took nearly a year to plan and produce. Originally tasked with creating an exhibition on children’s books, Herbert and Berlin dove into the manuscript collection, looking for anything and everything that might have resonated with an audience of readers under the age of 12. What they discovered along the way prompted a hasty redo.

“We realized that the concept of childhood as we know it wasn’t invented until the Victorian era,” says Berlin. While Confucian philosophy places importance upon the idea of play, and Islamic thought approaches childhood as a time to learn and be protected, Western philosophy and culture didn’t arrive upon the idea of childhood as a distinct developmental period between infancy and teenage until the 17th and 18th centuries. “They were just considered not-yet-adults instead of complete human beings. So having books specifically geared towards children wasn’t a thing until much later in history,” Berlin continues. “We started looking up fables and fairy tales that you associate with childhood instead. And what we were thinking of were the fables of Aesop.”

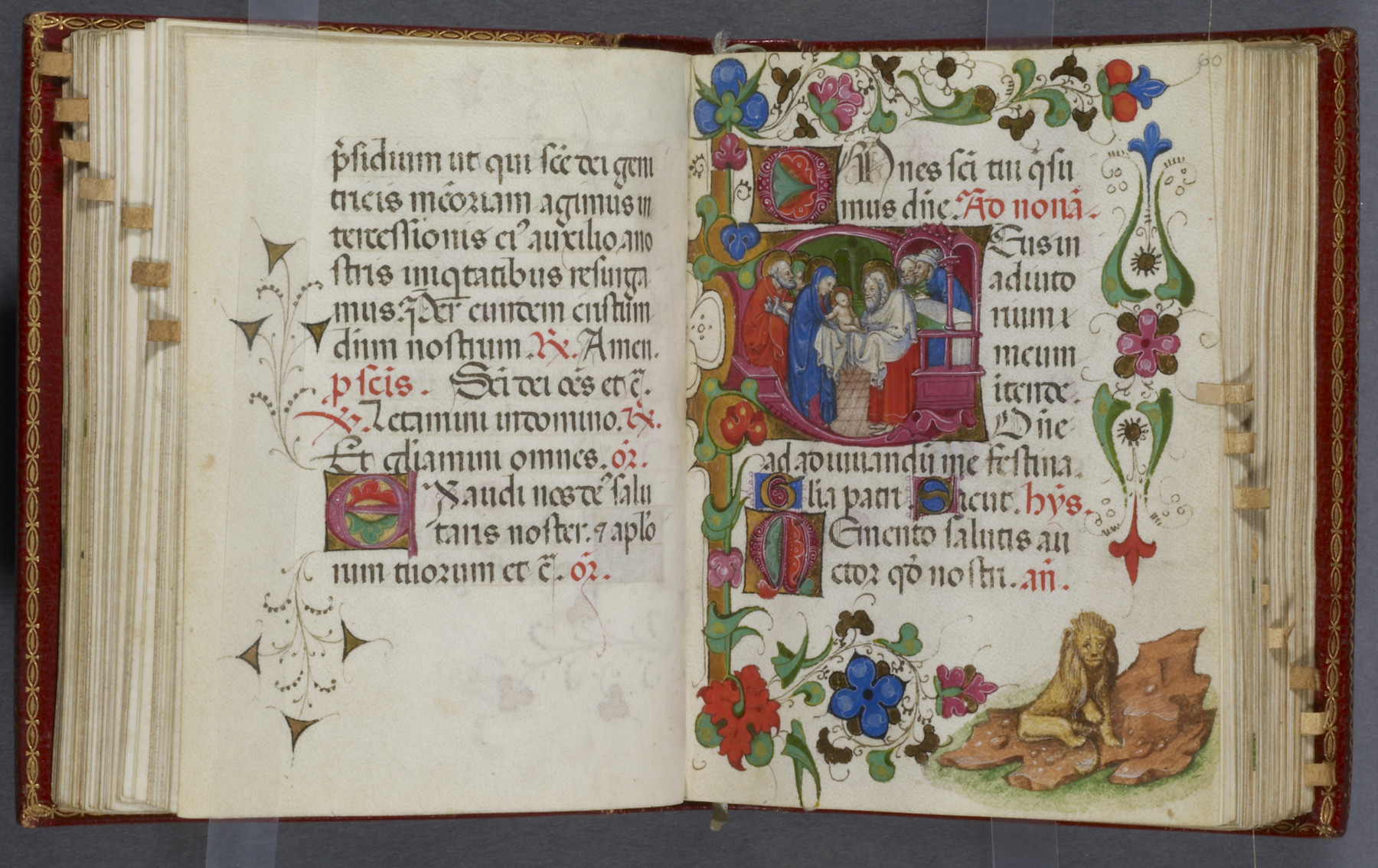

Aesop, the 6th-century BCE Greek fabulist whose stories have been transmitted across canons and cultures through the ages, begins the exhibition’s journey. The first case displays three medieval manuscripts where animals from Aesop’s fables decorate the margins, with delicate gilding and a primary color palette to offset the elaborate calligraphy. Readers of the time would have been able to recognize individual fables from the animals illustrated, highlighting Aesop’s popularity during medieval Europe, but also the time-transcending popularity of morality-based lessons told through the lives of animals.

Animal Tales (photo by Priyanka Kumar)

The second box, also from the Medieval era, features an arresting image: a tiny hedgehog that has used its quills to catch grapes. Originally described by Pliny the Elder as a way for hedgehogs to collect food for the winter, this tendency to trap fruit with its quills carries the animal into medieval bestiaries—illustrated manuscripts that blended ancient scientific knowledge about animals with moral lessons. The image has Christian undertones by this time in history—the hedgehog is now stealing the grapes, a direct reference to the devil, who plunders the spiritual fruits of mankind. The hedgehog is also tied up in the most fascinating way to Victorian England’s sternest art critic, John Ruskin—but I’ll let you go see that for yourself.

To traverse these 12 books is an intimate but rewarding journey. Lions, foxes, and even a unicorn appear as symbols, warnings and portents in these beautifully preserved manuscripts, hearkening back to a time when books were lovingly and meticulously crafted. Creatures—and their attributes—travel and morph through the centuries in this cozy museum space, aided by insightful wall text.

My biggest takeaway from the exhibition, however, is how much we take books for granted nowadays. “In this day and age, books are produced so inexpensively and so quickly, and not only do we have them physically, we have electronic versions,” says Berlin. “The fact is that the majority of the books in this show are ones that were being produced for the upper echelons of society.”

Being able to read was distinctive in and of itself in the Medieval-era, but the books from the period at the beginning of the show are the standouts of the show for other reasons. “Those are the ones that would have taken years to produce, using really expensive materials like parchment, gold leaf, expensive pigments,” Berlin explains.

“Hand-lettered, hand-drawn, hand-illuminated, hand-bound,” adds Herbert. “They’re not just books, they’re status symbols. They’re evidence of conspicuous consumption. They’re an emblem of wealth and status in society. So much of what we have in the manuscript collection was made for wealthy people—kings!—to look at in private, but it’s important to also remember that Henry Walters died and left the collection to the city of Baltimore. So as curators, our job is to build on this philosophy of telling an engaging story that people can see and connect to.”

To Agree Like Cat and Dog, ink on paper (ca. 1490)

Which brings us back to visual culture, and picture books, which everyone loves.

The simplest illustration in the exhibition is from a book of proverbs: a line drawing of the pen-and-ink variety, showing a dog and cat in a meadow. The dog seems to be snarling at the cat, which in turn stares angrily out at the viewer. The phrase is familiar—fighting like cats and dogs. “It’s not like everyone could read by 1490, when it was produced, but it’s being produced on paper, it’s being produced more quickly, the art is simpler, the book has now become a form of entertainment.” Herbert says.

And there it is, a tiny lesson in the history of book production encapsulated in a small but powerful exhibition: The closer we move toward our present time, consuming and engaging with books turns into an inexpensive, quick, and popular form. The earlier tomes on display here—expensive, private, liturgical, devotional texts—are more sparsely illustrated, but with color, calligraphy, and gold foil.

Herbert drives this curatorial decision home with a few words: “We only have about two hundred words (on the labels) to get across what’s happening, but through this exhibition you can trace the trajectory of the illustrated book across three centuries while also looking at the way stories about animals travel and transform across cultures.” With two complementary but different narratives, Animal Tales certainly encourages one to think of books not as objects, but as living entities.

(Photo by Priyanka Kumar)

Animal Tales is on view at the Walters Art Museum through August 11.

Images courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, except where otherwise noted.