A deluge of aquatic imagery from a fish pond and the rush of wet sounds submerge the viewer, immediately upon entering the gallery. It’s a shimmering environment, where videos ripple across the massive, undulating surface of a river of paper casts of single-use plastics that cascades dramatically down the wall into the viewer’s space. Moving further in, you encounter stalking sharks and island seascapes, as well as the repeated and disconcerting presence of the forgotten little paper ghosts of all the plastic objects that flood our daily lives.

Washington, DC-based artist Rachel Schmidt’s videos and the ethereal aural elements composed by Baltimore musician om.era.kev in All My Children Sleep in the Sea, on display at the University Gallery at Salisbury University through December 7, effectively convey a sense of the permanent damage humans inflict on the aqueous world around them. The multi-sensory environments in the exhibition are a prescient examination of the problems facing the delicate balance of our aquatic ecosystems—something that literally hits close to home on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and the larger Chesapeake Bay area.

Schmidt’s installations build on the aesthetic dialogue with our natural environment that began with the earliest landscape paintings and grew to encompass the expanded field of Earth Art in the 1970s. However, Schmidt doesn’t just portray the sublime threat and beauty of nature, or make her mark by digging into the environment the way Earth artists did. Instead, through the combination of temporary video imagery, the forgotten permanence of discarded plastics, and the balance of sounds and silence, Schmidt demonstrates how humans recently inverted the sublimity of the landscape, threatening and harming the awe-inspiring beauty that surrounds us.

Rachel Schmidt, All My Children Sleep in the Sea at the University Gallery at Salisbury University

Earth artists such as Robert Smithson made their marks in the midst of the nascent environmental movement (Richard Nixon founded the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970). However, Smithson cared more about the durational passage of time and the entropic forces of nature marked on the surface of the permanent basalt spiral in Utah’s Great Salt Lake, than the impact his work had on its surrounding ecosystem. By contrast, Schmidt’s environments are poignantly juxtaposed with an ominously glowing cairn, built from stacks of paper-cast remnants of consumer culture—part of the artist’s commentary on the visible consequences of recent laws that rollback prior protections and endorse the mass consumption of single-use plastics.

Schmidt sculpts with light, a natural extension of her formal training as a sculptor. She projects time-based video imagery onto built environments constructed with paper ghosts of the plastic soda bottles, yogurt cups, and take-out containers that flood contemporary life, as well as onto more traditional painted two-dimensional works in her projection drawings. Schmidt and om.era.kev’s environments submerge the viewer into an all-encompassing world where the numerous human-made threats that face all waterways become palpable.

Schmidt demonstrates how humans recently inverted the sublimity of the landscape, threatening and harming the awe-inspiring beauty that surrounds us.

In the eponymous work, “All My Children Sleep in the Sea” (2019), Schmidt recorded videos of sharks swimming amidst schools of fish at the National Aquarium in Baltimore. The predators and prey ominously glide across various scrims of transparent fabric that surround the viewer as they walk into the work. Moving through the work, amidst the projected sea life and hand-painted ruins of vessels that sink into shimmering, watery depths, one hears the strains of a poem that Schmidt wrote from the perspective of nature and aquatic life, disrupted by wooden echoes of a marimba that float across the gallery from “Breach” (2019). The buoyant tones of the marimba and the soft pauses in the poem punctuate the simultaneous feelings of uneasiness and amazement elicited by the circling predators and the looped, abstract fears and anxieties of nature, which emphasize the precarious reality of the oceanic world.

The sharks allude to both the traditional sublime in the potential threat of their awe-inspiring power, as well as the inverted sublime, as their primeval perspective reflects the reaction of the marine world to the seismic shifts caused by humanity’s relatively recent interventions in the environment. While the sublime traditionally signals a form of exalted experience in nature, Schmidt’s imagery inverts the lofty exhilaration of the sublime to reveal the base reality of the indelible marks made in the natural world through our common consumption of a disposable culture, the reverberations of which will persist for generations.

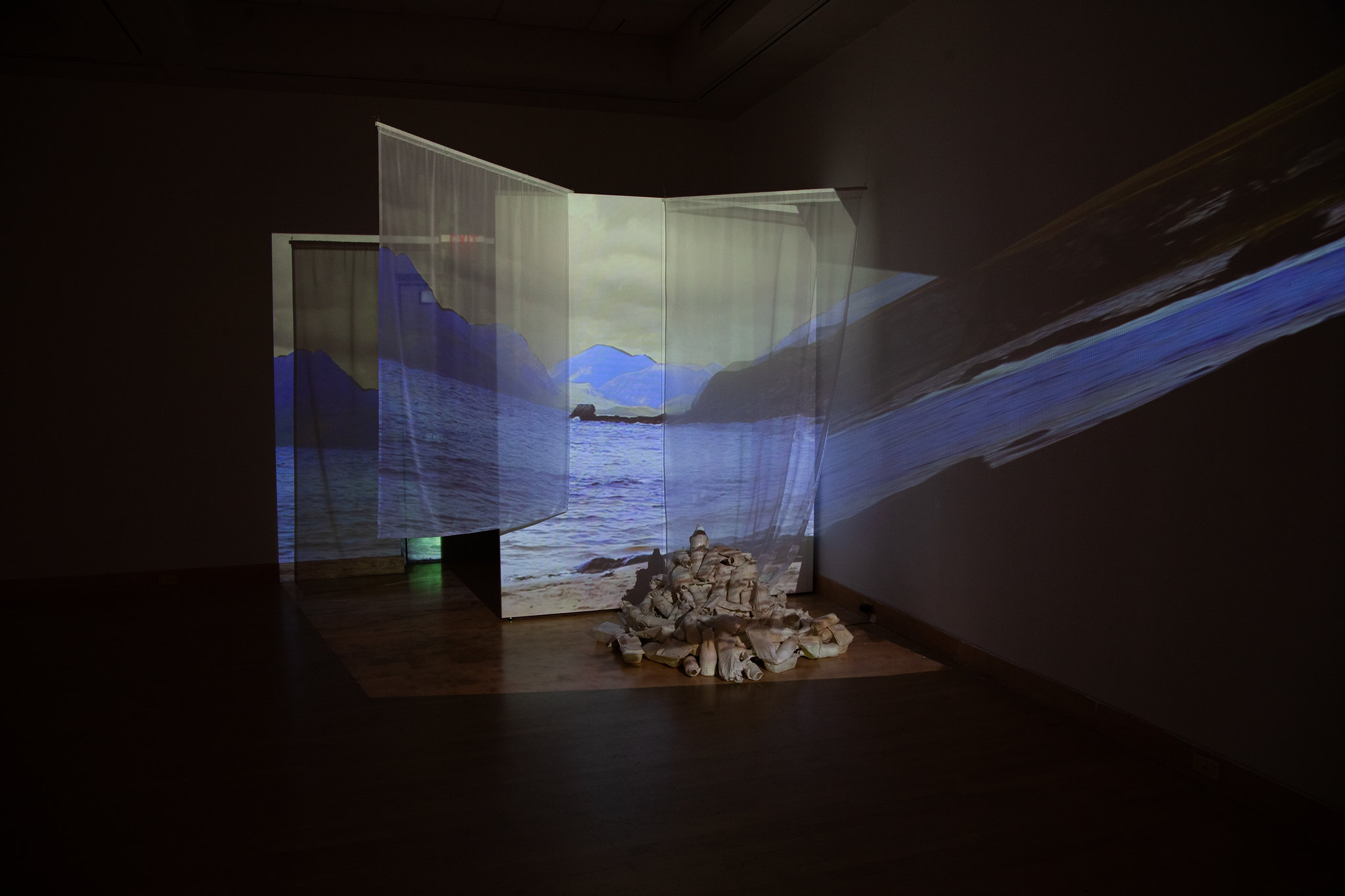

Other works that suspend the viewer in a contemplative, aqueous meditation are “Trash Cairn” (2019) and “Drowning” (2017). In “Trash Cairn,” Schmidt responds to her experience on the Scottish Isle of Skye with a looped video of land- and seascapes projected at a raking angle on the walls and sheer voile fabric that hangs from the ceiling. An illuminated cairn sits amid the projected images of the isolated island, surrounded by the sounds of water running across the surfaces of mass-produced stainless-steel sinks and drains, as well as om.era.kev’s hands and pot-lids. As Schmidt noted in an artist talk, cairns are inherent parts of the remote landscape of the Isle of Skye as landmarks and funerary barrows, but she replaced the typical stones of these monuments with recycled paper casts of plastic refuse to highlight the permanence of the forgotten, single-use objects cast into an unseen trash heap.

In “Drowning,” Schmidt reflects on her experiences in the Taipei Artist Village in Taiwan and the aggressive recycling tactics the small island embraces to combat the environmental damage from accumulating trash. Her river of recycled paper ghosts of plastic trash, and the shifting images of a fish pond projected across its surface, create a tangible anxiety, reminiscent of what Schmidt felt after returning to the US from Taiwan; although she found her experiences in Taipei heartening, she realized that the rest of the world is still drowning in plastic.

Rachel Schmidt, All My Children Sleep in the Sea at the University Gallery at Salisbury University

Schmidt also projects imagery that she recorded in Taiwan onto the gleaming vinyl triangles of the projection drawing, “Out of Balance” (2019). Looped footage from Taiwan blinks across the reflective surface of a central, isosceles triangle, flanked by two other chrome vinyl triangles. The left triangle bears a bundle of plastic bottles in its center, painted with scenes of a protected forest/ A pyramidal cairn stands at the base of the triangle on the right, stacked from paper casts from the stones in Schmidt’s garden. The geometric forms underscore the typically algebraic over-simplification of the truly complex network of actions required to actually balance the environment.

In another projection drawing, “Breach,” footage of flood zones of the Great Plains of her home state, Kansas, floats across the painted surface of a landscape in which boats stranded in a grassland creates a jarring disconnect between the reality of today and a potential future, in which these regions that once occupied the bottom of a prehistoric ocean might recede beneath the waters again. Om.era.kev accentuates this disjuncture between the painting’s and video’s imagery, confronting the viewer with the soft rustling of burning paper, instead of rippling water, punctuated by the tones of the wooden marimba. The arrangement of sound, video, and painted imagery are subtly reminiscent of the larger impact that our individual, daily actions have on our planet.

As viewers stand in the midst of the voile scrims in All My Children Sleep in the Sea and sharks stalk the waters projected around them, the transparent fabric allows one to peer out onto the other recorded landscapes and plastic rivers that haunt the environment in a poignant visual dialogue. The overlapping of objects, imagery, and sounds in the exhibition create multi-sensory, meditative environments that bear the signs of our fragile world. The simultaneous visual and aural clash that Schmidt creates between the flickering images of the seemingly eternal landscape that once threatened humanity, and the indelible marks of humanity that now endanger the environments around us, remind the viewer of the multifarious ways we continue to invert the sublimity of nature.

Rachel Schmidt, All My Children Sleep in the Sea at the University Gallery at Salisbury University

All My Children Sleep in the Sea is on display at the University Gallery at Salisbury University through December 7. For more info, visit the gallery’s page.

Photos by Mehves Lelic, courtesy of Salisbury University

Jennifer Kruglinski earned her BA in Art History from Rutgers University, and her MA and PhD in Art History from Stony Brook University. She is an Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History at Salisbury University on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Prior to joining SU, Jennifer taught art history at CUNY, Bergen Community College, Rutgers University, and Stony Brook University. Jennifer also worked for the Parrish Art Museum in Bridgehampton, NY, and wrote several essays for their East End stories website. She also wrote and edited several articles for the Art Story Foundation’s website. Jennifer’s research focuses on feminism in Modern and Contemporary Art History.