Absence makes the heart grow fonder. We all know this, but when you’re experiencing a traumatic loss it’s difficult not to place it on a pedestal or polish it into a gleaming fantasy. If you are a 2020 graduate, you have a right to mourn this rite of passage, this pinnacle of excellence, this moment of triumph, taken from you by a viral pandemic and a country that didn’t make much effort to avert it, but you should also know that the collective graduation ceremony is a symbolic event; as an actual experience it never quite lives up to the hype.

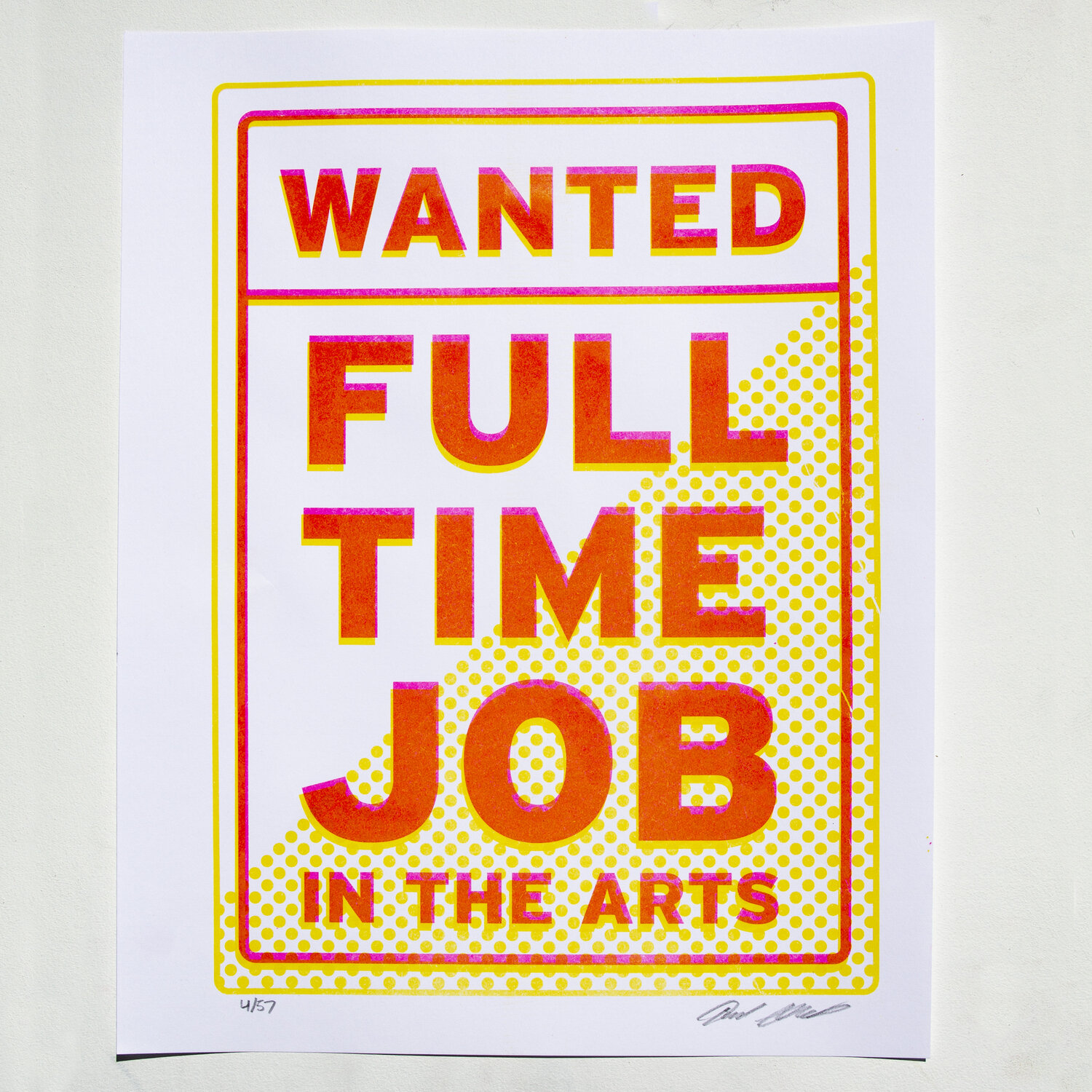

This is (clearly) not an official graduation speech. I am not writing this for any particular age group or grade level, a specific program or genre of study, although I am an academically trained artist and feel an affinity for art school and liberal arts graduates. Whether you are a newly minted chemical engineer, MBA, lawyer, or English major, this advice is uniformly applicable: 2020’s non-graduation is a symbol of what you have lost, but it should be the least of your worries.

After decades in education and teaching, I have acquired a respectable amount of graduation experience. I have taught college students, graduate students, art majors, non-art majors, and spent seven years teaching art to high school students in Maryland public schools. I have graduated at least four times myself that I can remember: high school, college, graduate school, and then graduate school again. I am not an expert on the subject, but I have learned through personal experience that graduation ceremonies are designed to be tolerated and photographed, but rarely enjoyed.

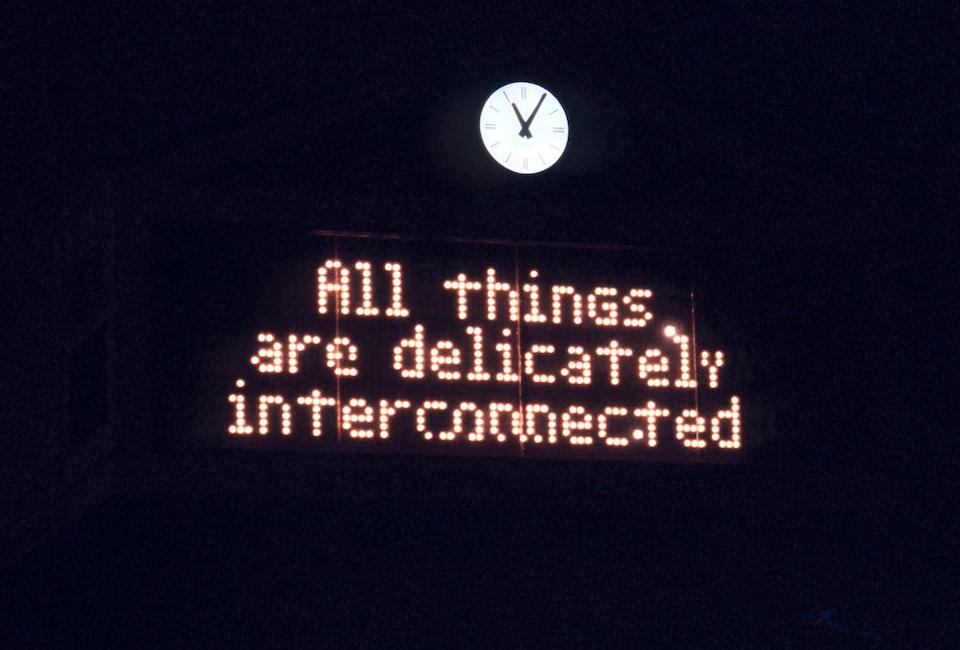

I have heard my share of rambling graduation speeches full of non-specific platitudes, but I also know when a speaker has nailed it. (Strange coincidence: Sam Gilliam was the keynote speaker at both my undergraduate and MFA ceremonies.) When there is cheering, unsolicited clapping, knowing smiles, and tears, a graduation speech has done its job. Or has it? Is a graduation speech (and ceremony) a mission-accomplished placeholder of a moment designed to make students and parents feel good about themselves in a generic and mass produced way, or can it actually teach us something valuable?

I graduated in a high school class of 433 students. That ceremony taught me that alphabetical order seldom produces close friendships and listening to names being read for three hours is boring as hell. In college, I recall winning some sort of award at graduation and the art department chair pronouncing my name incorrectly as I crossed the stage. So much for making an impression in those four years, huh? The main thing I remember is the nightmare-level terror of almost missing the ceremony—in a carpool with my fellow art majors, driving around cluelessly in circles in the neighborhood surrounding the college I had just attended for four years, completely lost before the driver admitted he was stoned. Learning opportunity: getting high before graduation might make the speeches more interesting, but wait until you have arrived safely at your destination.

Fast forward to graduate school. I was twenty-three the first time. I don’t remember much about this one, except it was a degree in education from my dad’s alma mater where he was a career professor. My greatest treasure from that experience is not my diploma, but a photo of me and my dad wearing funny hats and robes. It was a beautiful spring day and my dad’s smile is playful and proud.

As a high school art teacher, I was required to attend graduation in academic robes and sit on the end of a row of students to keep them quiet. I was in my twenties, barely older than my students, and I remembered one great lesson from my college graduation: I met up with several other teachers at a bar before the ceremony, and then we walked to graduation in a pleasant haze. This actually made the experience more interesting, and the keynote graduation speaker, typically a favorite teacher with decent oratory skills and good sense of humor, even more fantastic. I remember one beloved physics teacher making the entire senior class repeat two words of wisdom out loud as a group: “compound interest.” I wonder how that has resonated with this group, now in their mid-30s?

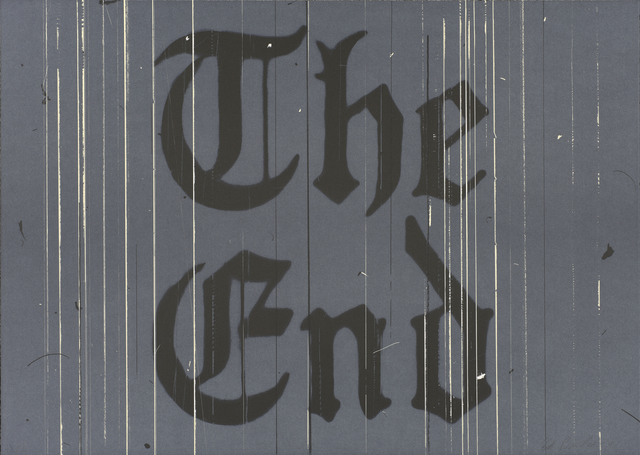

My last graduation ceremony was in 2005 for an MFA from MICA. I attended a low-residency program over four summers, so graduation occurred a year after I had completed my studies and felt like an afterthought. This was a comparatively sober, mature graduation, and I remember sitting in parking lot traffic and group photos on the hill in front of the Station Building and Sam Gilliam, yet again my graduation speaker. My main memory from that day is that it rained and my black graduation gown bled a weird purpley color on my cute white pants that never came out, my one souvenir besides a diploma.