For most of a year, I stayed indoors. When I could not leave home, listening, reading, learning, and talking felt like active things I could do to engage my senses and relationship with the world around me. Not being able to participate in the world in a palpably meaningful way compelled me to pay closer attention to how I’d been listening and what I’d been hearing, and this heightened awareness has altered the way I record memories.

The past year has broken down huge chunks of my life into plainer compounds. Senses are stimulated, heightened, then dulled in waves. On a late summer day, I stayed outside in the warmth and listened to the audio version of a long essay by Alexander Provan, which functions as the intro text for Triple Canopy’s Two Ears, One Mouth issue that explores the valences of speaking and hearing. Near the end, Provan considers the limitations of listening during a time of intense solitude:

“To me, the convenience of experiencing the world from home—the ease of broadcasting and consuming voices, logging on and off—is also a reminder of how much I can say and hear without changing myself or others, without having any revelations or provoking any doubts. In other words, I sense the media working on my thoughts, my being; I feel like an avatar of a strangely dualistic notion of communication, which insists that I speak or listen, act as a free agent or an obedient receptacle.”

Those lines made me want to consider the pandemic’s effects on my senses, particularly what I was hearing and listening to. I’d been absorbing media urgently, frantically, and passively, even when I was already saturated. And I’d been using that desire for knowledge as a coping mechanism: If I can try to understand where we are and why, I’ll gain some kind of control over it.

Paying attention to how I’m listening reminded me that despite how it often feels, the world is still way bigger than the small life the pandemic had circumscribed for me. Even just the ordinary sounds that interpolate my day—church bells from Greenmount, a rush of cars down the street, the cat’s meow, the neighbor’s whistle, the domestic tedium—became a little more special. Going out for a walk, overhearing conversations and music blaring from car windows, seeing little kids trying to ride their bikes up the sidewalk—these moments expanded the smallness. But only when I let myself notice them.

Those are the ambient sounds. What about the sounds I’ve intentionally sought out? Aside from the informative distraction of so many podcasts, there’s the music that gives me comfort, the old staples, and the jazz records my boyfriend’s getting into. My music listening has slowly wound down over the past couple of years but especially so last year, with fewer occasions to really listen. No trips, fewer walks, no bus rides, and even less psychic space. But I think that’s made the music that I have sought out more memorable. Despite my gerbil-sized attention span, there have been several albums by Baltimore artists, released since the pandemic’s start last March, that have blessed me with twenty or forty minutes or an hour of something else to sit with. Some of these records inevitably confront themes that are pertinent to our present circumstances and upheavals, some take the listener to places subterranean or extraterrestrial, and many others pull off an inventive combination of all the above.

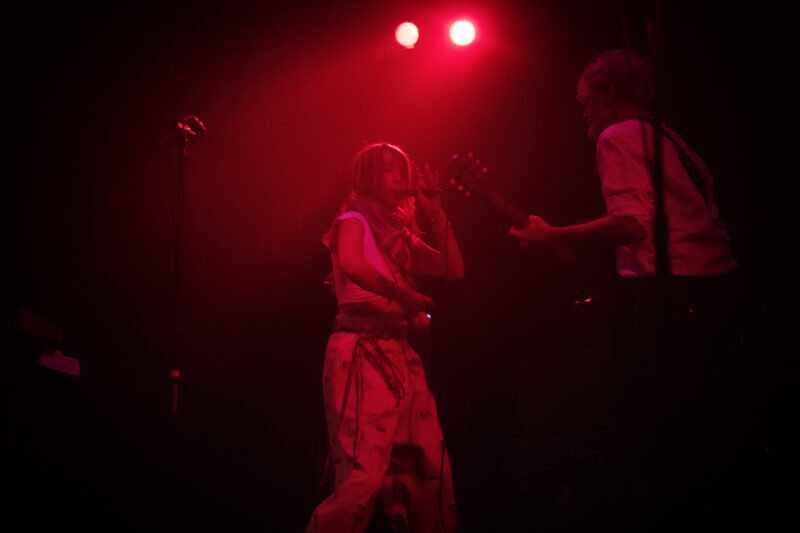

Listening to the following albums, I think about a few minuscule but memorable aspects of going to shows (aside from temporary hearing loss) that have little to do with the music: the awkward run-ins with people you sorta know, the way a spilled beer makes your shoe stick to the floor, and the foreign/familiar scent of someone else’s sweat. These things mean nothing and everything, and I guess right now I’m seeking any and all reminders of how we used to live, thinking about what we’ll leave behind when we can re-emerge. Parts of the before-times are intangible right now, but their memories do ring through when listening to the sounds of this city.