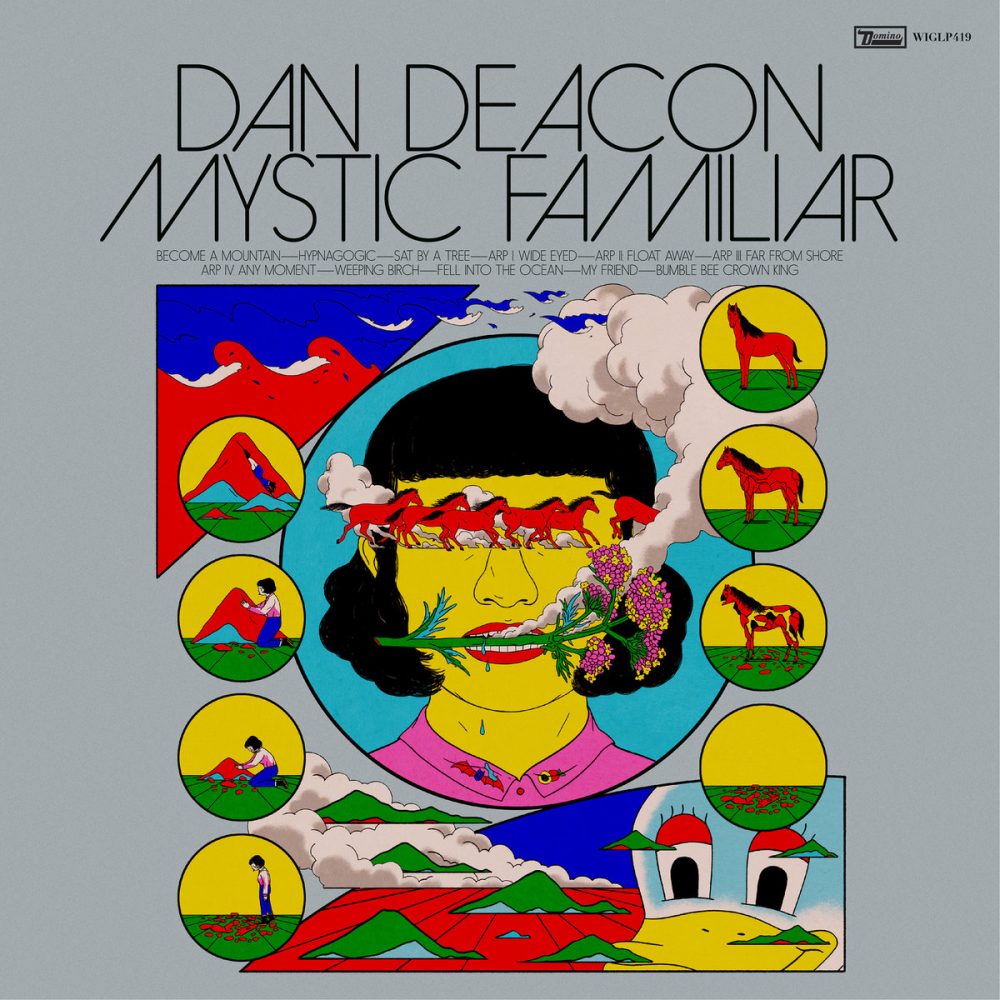

From the gallop of rhythm, the noise of experimentation, and the pleasure of listening, music is a boundless form. Every Friday night on Baltimore’s radio station WTMD (89.7 FM), Dan Deacon shares two hours of music that allows the listener to meditate, placing them into a healing trance. The program, Distorting Time, broadcasts mainly long-form music pieces, many of which have a unique experimental spirit. Since Distorting Time debuted in February, shows have included artists as various as Steve Reich, Herbie Hancock, Philip Glass, Meredith Monk, Sly and The Family Stone, CAN, and Fela Kuti, among many others.

A music alchemist rooted in Baltimore, Deacon has worked with many local musicians, including Matmos and Future Islands, on his own music for years. His earliest albums, including Goose On The Loose, Meetle Mice, and Silly Hat Vs. Egale Hat, came out when he was still a student in the Conservatory of Music at SUNY Purchase. These early works function as creative trial periods for personal exploration and actuating the idea of how to interact with music. They are experimental, blaring urchin-like vaulting beats and abstract noise.

With 2007’s Spiderman of the Rings, released a few years after Deacon moved to Baltimore, the artist combined his academic composition background with the noise aesthetics of avant-garde electronic music, mounting vivid and playful rhythms and ecstatic pulses. Subsequent albums, such as Bromst (2009), reflect Deacon’s participation in local DIY music and art communities like Wham City, Whartscape music festival, and the Baltimore Round Robin Tour. America (2012) is forged from Deacon’s experience of touring and performing around the country, but it’s also layered with personal indignation towards war and the eschatological anxiety of capitalist supremacy. His next release, Gliss Riffer (2015), minimized some of the ornate sound and noise that characterized his previous albums and returned to arrangements that emit his musical energy more intuitively. In the following years, he composed film scores for the documentaries Rat Film, Time Trial, and Well Groomed.