The cabinet of curiosities, from the German wunderkammer, was a 16th-century proto-museum. Usually a room in one’s home rather than a piece of furniture, the cabinet of curiosities was often stacked to the rafters with all types of objects: bones and other wonders of the natural world, relics, antiquities, works of art, and so on. These rooms served as a status symbol and an entertainment space for nobles, aristocrats, and members of the burgeoning mercantile class. The rarer the object, the more value it held for the collector seeking to solidify their status as a learned person in the eyes of their guests. While many of these spaces evolved into natural history museums, they were primarily—as the name suggests—places of wonder and imagination: What does the world outside of one’s local 16th-century travel radius look like? What magic lies therein?

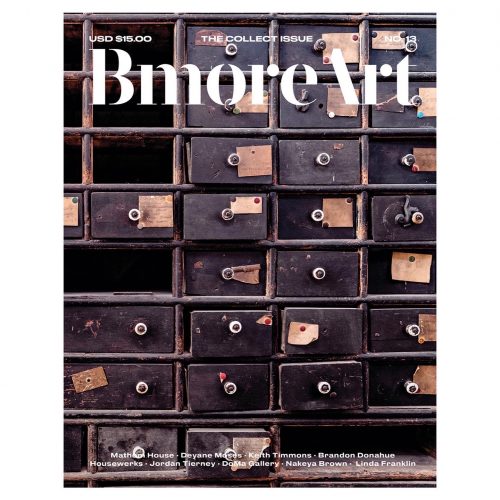

Entering the wood-floored room, lined with brightly lit display cabinets and collages of old photographs, on the third floor of Benjamin Kelley and Morgan Kempthorn’s Baltimore home feels a bit like walking into a cabinet of curiosities from centuries past. The room is darkened: the windows are curtained for preservation purposes, the floors are covered with rugs, and there is a velvet rocking chair, all of which creates an almost theatrical sense of intimacy.

“We have a very specific aesthetic for the space,” Kempthorn says. “There’s something really lovely about the moment when you open the door from downstairs and it feels detached from the house, disassociated from everything else. It feels like a portal that you walk through.”