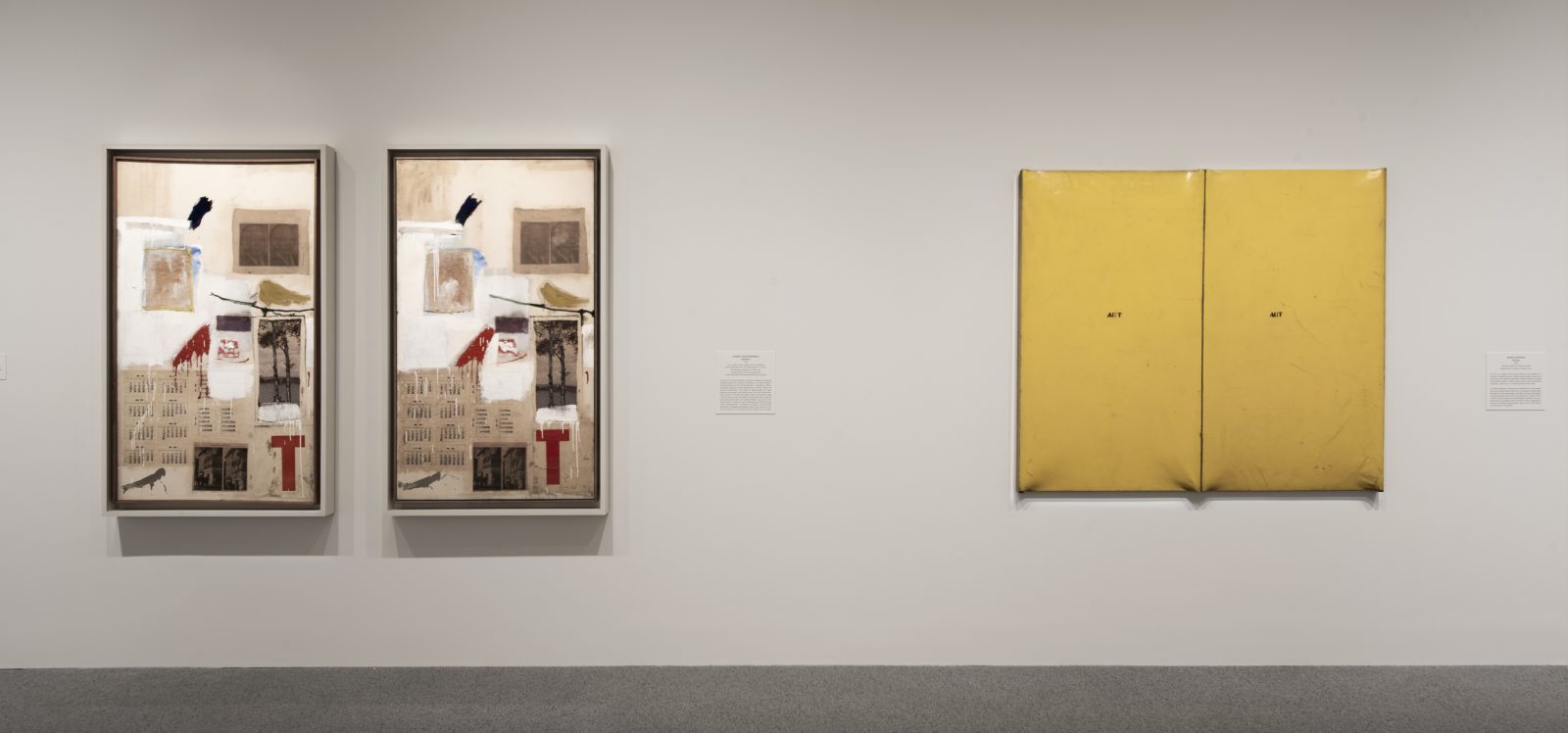

In corresponding locations on each of Robert Rauschenberg’s paintings Factum I and Factum II are two printed photographs of a burning building, a snapshot of two trees, two faded images of Eisenhower, and a print calendar for every month. Each element is a copy of a copy, contained within a composition that is itself a double, but there is no genealogy that can be traced to locate an “original.”

Currently shown together in The Double: Identity and Difference in Art Since 1900 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the two paintings were executed simultaneously in 1957. The artist moved back and forth between each painting, attempting to replicate his own gestural brushstrokes down to the drips of paint running down the canvases. But because the two canvases were painted at the same time, it is impossible to determine which drips came first. They are no less artificial than the print reproductions strategically adhered to the canvases. Celebrated by abstract expressionists during the same decade, the artistic ideals of spontaneity and authenticity collapse in the Factums.

Almost. Close looking reveals failures in Rauschenberg’s attempted transcription of each mark to the opposite canvas: one brushstroke is more curved than its twin, or the placement of another seems a bit off. The paintings are marked by similar asymmetries—or dissimilar symmetries. There’s a certain satisfaction in spotting these variations; a reassurance that singularity of expression is real and meaningful (and commodifiable: “one of a kind”).