Morels, chanterelles, chicken of the woods, lion’s mane, hen of the woods, fiddlehead ferns, ramps, black walnut tree sap, trifoliolate orange, paw paw, salt—the edible landscape of Maryland stretches throughout the seasons for forager and Chef Chris Amendola. It takes a heroic effort to seek and gather edibles from our forests—a task in which the Foraged Eatery owner takes great pleasure.

Nearly all of the forest along the eastern coastline of North America were razed for fuel, lumber, and farmland by European colonists. Today, deforestation has been identified as the second leading cause of climate change, second only to burning fossil fuels, and accounts for 20% of greenhouse gas emissions. Forests are leveled, burned, and cleared to make space for large-scale agriculture, destroying natural carbon sequestration in exchange for soy farms or cattle grazing. Yet, canopies of trees reemerge and arc and bend in resilient forests.

If deforestation has an opposite, foraging might be it. To forage food in the natural landscape of a forest, or to crystalize salt from the waters of the Chesapeake Bay, is simply a chore, but to serve it on a plate in a restaurant centered around the mission—is narrative art.

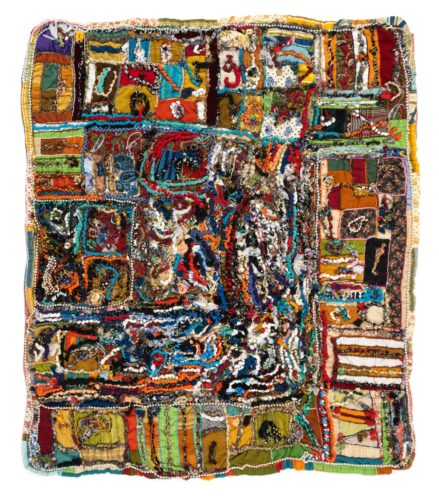

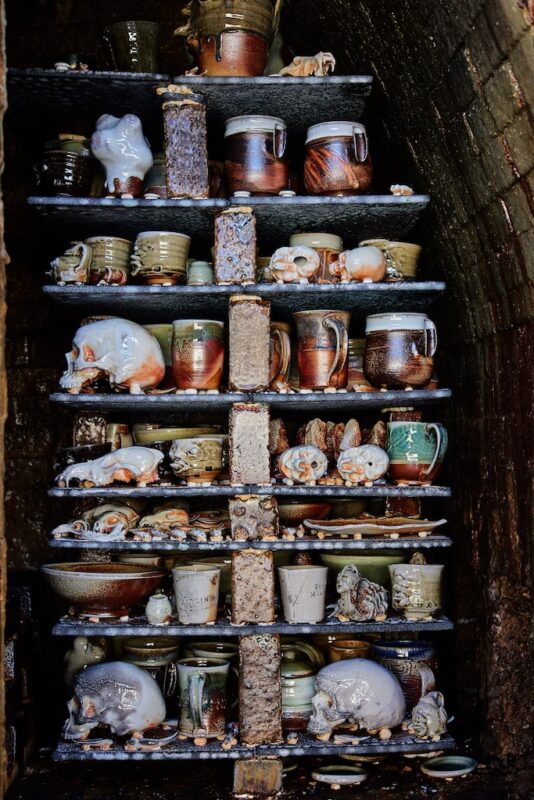

The flesh of an orange and white fruiting mushroom, plucked carefully from the bark of a 200-year-old tree, mixed with locally grown and milled grains, tossed in fragrant seasoning, pan-fried, and served on a hand-crafted ceramic plate made by a Baltimore artisan—the presentation and the food become a vessel for storytelling. A transient tale of life, death, abundance, and loss. The story of our region, our city, and the nation that it lies within.