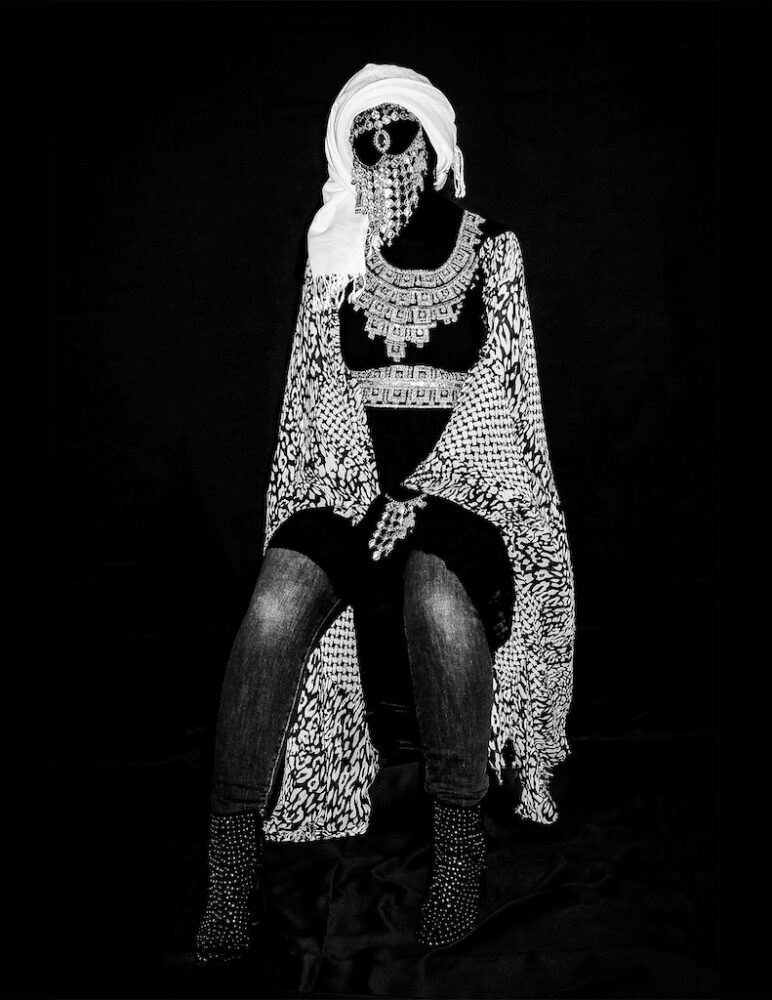

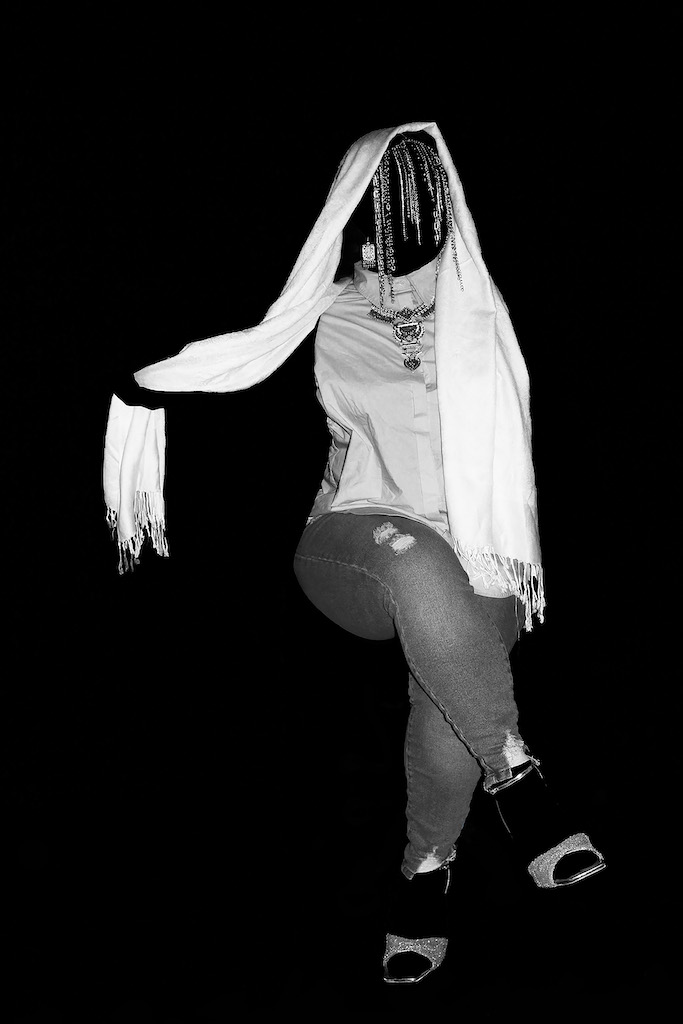

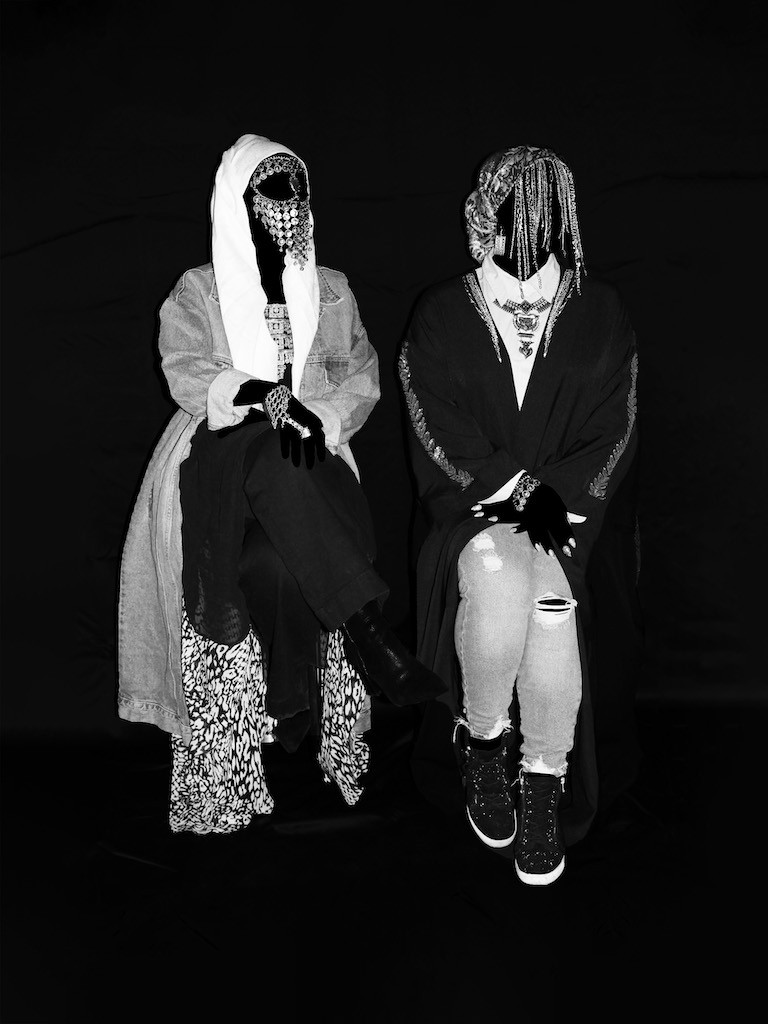

Anysa Saleh’s photography challenges established methods around portraiture, but her practice is based largely around Yemeni cultural traditions, where it is taboo for women to be depicted photographically. In the bold black and white photographic series titled The Daughters of Yemen | بنات اليمن, Saleh explores a variety of profound dualities faced by Yemeni-Muslim women living in the United States.

“In front of the camera I am fully myself—the daughter my mom and dad raised me to be,” says Saleh, sitting comfortably yet poised, with her head high and shoulders back. That posture epitomizes the aspects of every woman she seeks to capture in her photographs.

Returning to her art practice after a five-year break, Saleh is positioning herself (and others) in front of her camera in order to confront the contradictions she experiences as a Yemeni-Muslim woman living in the United States, but also to harness the power of portraiture to capture a sitter’s essence without their actual visage.