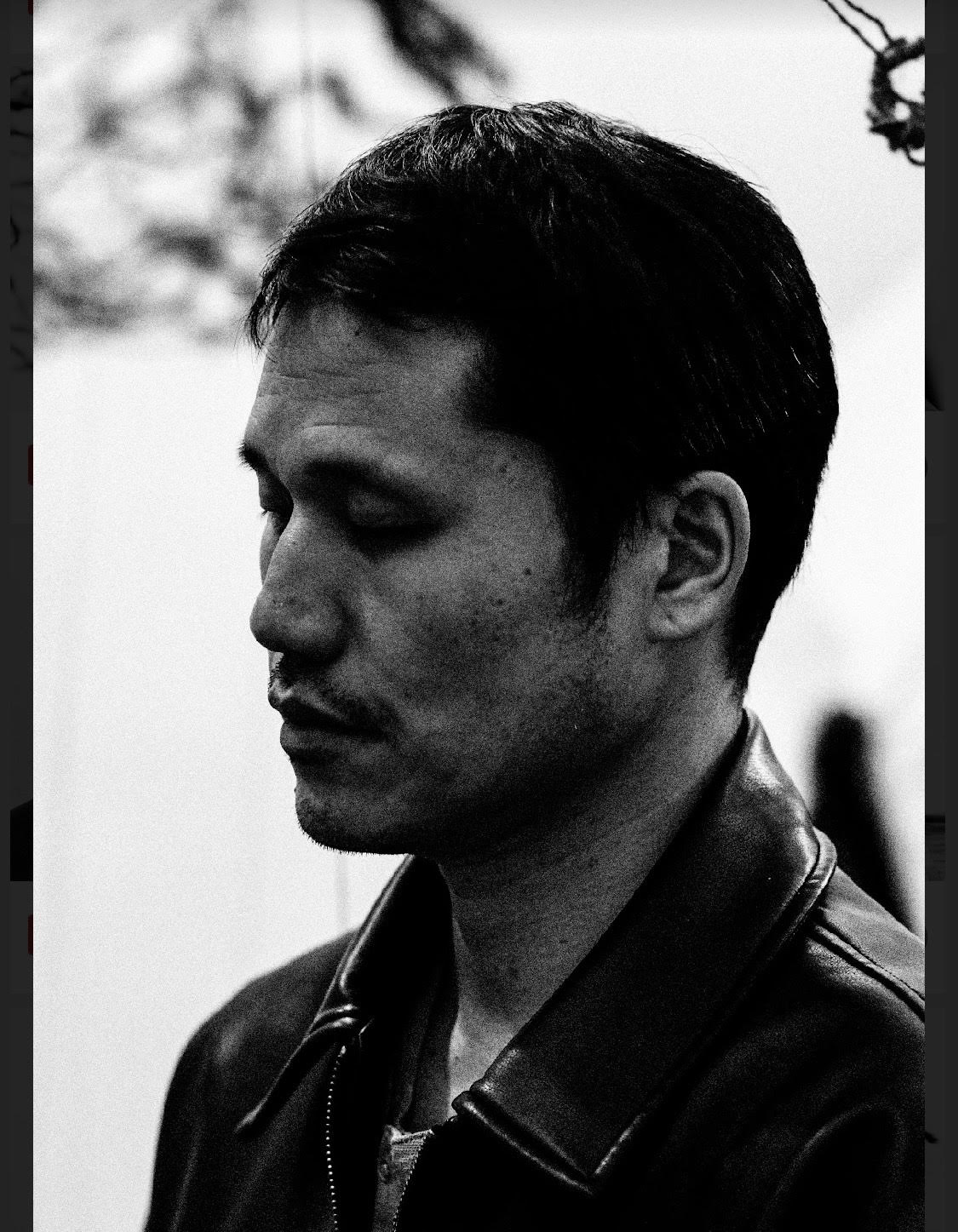

Music as eerie as dark night and the morning dew: the first time I really got to know Dirty Beaches was their show at The Wall, a venue in Taipei, April 2014. The broken, gloomy, noirish, and low-fi aesthetic somehow sounded cold, with extremely fierce vocals from the performer on the stage. Holding the microphone tightly, he sang and shook his body most intuitively as if trying to pour out all the emotions of the music and penetrate into every last cell of the audience members.

Dirty Beaches was the alias of Alex Zhang Hungtai (who has also worked under his first stage name Wrong Karweis, as well as Last Lizard). Born in Taipei, Taiwan, in the 1980s Hungtai immigrated to Canada as a child. He used to work in a video store in high school, immersing himself in a world of movies daily, and thus came upon the films of Wong Kar-wai and Hou Hsiao-Hsien.

The artistic background accumulated in his youth has shaped his music with a unique and strong visual texture. Most of his life has been in a state of drifting and moving. The meaning of “home” is like a collage of fragmented landscapes in his music. Because of this, there is always a strong sense of diaspora and nostalgia in the Dirty Beaches period—with montage and cinematic soundscape expressing the beauty and sadness of things flowing in time.

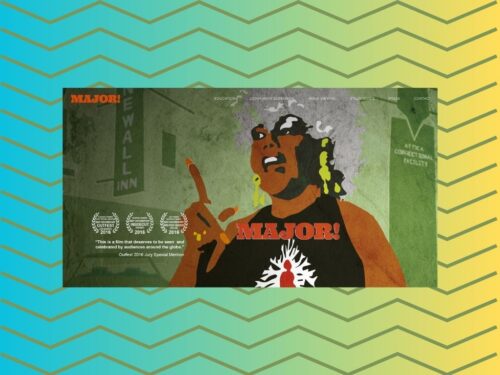

Although Dirty Beaches was disbanded in 2014, he continued to make music under his name, Alex Zhang Hungtai, which gradually transformed into different sound forms. Most of the long-format pieces he released are akin to running through a kind of sound swirling like an infinite continuation and loop. He also participated in the scoring of the film “August At Akiko’s” and “Mountain Woman,” and made a guest appearance in season three of “Twin Peaks” with the trio Trouble, alongside Dean Hurley and Riley Lynch.

The way that Hungtai approaches music seems to constantly explore the meaning of existence in this world. Now most of the pieces of nostalgia in his music are gone, but he has integrated his own cultural and traditional heritage into his body and continues to apply his musical language, expressing subtle feelings about being in different lands and the ever-changing world.

As Ryuichi Sakamoto wrote in the anti-biographical experiment book Skmt, who is Ryuichi Sakamoto: “Moving in a new land. Be alert. Language, color, habit, and smell. Alone in a world where everything changes. Nerves and body, no matter how small things are, pay attention to them, not to be missed, little voices, etc., sensitive to small changes in the outside world.“