The essentials of the artist statement are as following:

1. Materials and Media

In an age where art is usually experienced first online, you need to explain to the viewer what the work is. It can be impossible to tell whether we are looking at a film still, a site specific installation, or a painting. Don’t assume your viewer knows what and how you do it. Be generous with them! Always include an explanation of your media and process, and how material culture enhances the meaning of your work. What materials and tools do you use? How do you create your work? Be as specific as you can about what makes your work unique and how your materials reinforce your ideas.

2. Concept and Subject Matter

Your subject and concept are not necessarily the same thing. Your subject is the actual stuff you depict or reference. Your concept is the reason for doing so, the idea underneath it all. For example, an artist paints figurative portraits of individuals in natural settings in order to explore identity politics or expand the art historical cannon. Their subject is the people depicted, but their concept goes deeper and offers their reason for making the work in the first place.

3. How these two aspects – material and content – reinforce or contradict one another? What does your work DO? What sets your work apart from other work being made that appears to be similar?

Sometimes one’s material and concept work together within a longstanding tradition. For example, if you’re an oil painter of pastoral landscapes, you are working to expand an established tradition. Even if there is a contemporary or environmental aspect to your work and you are painting strip mines or disasters caused by global warming, your work benefits from the historical constructs set forth by artists who came before you.

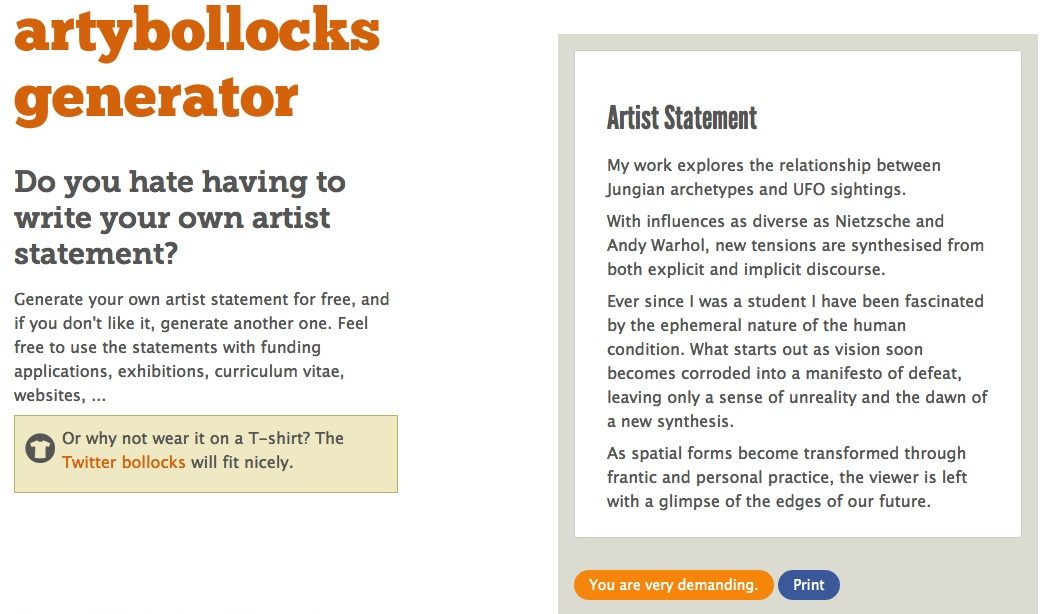

Usually, and especially with contemporary art, work tends to buck or subvert established art historical traditions and this is what gives it meaning. If you are a fiber artist working within the tradition of colonial lace-making, but you’re depicting pornographic images in a doily, you’re subverting the tradition and challenging expectations of your medium.

Use active words — like explore, analyze, question, test, search, devise, discover, balance, connect, experiment, challenge, or construct.

Additional, optional aspects:

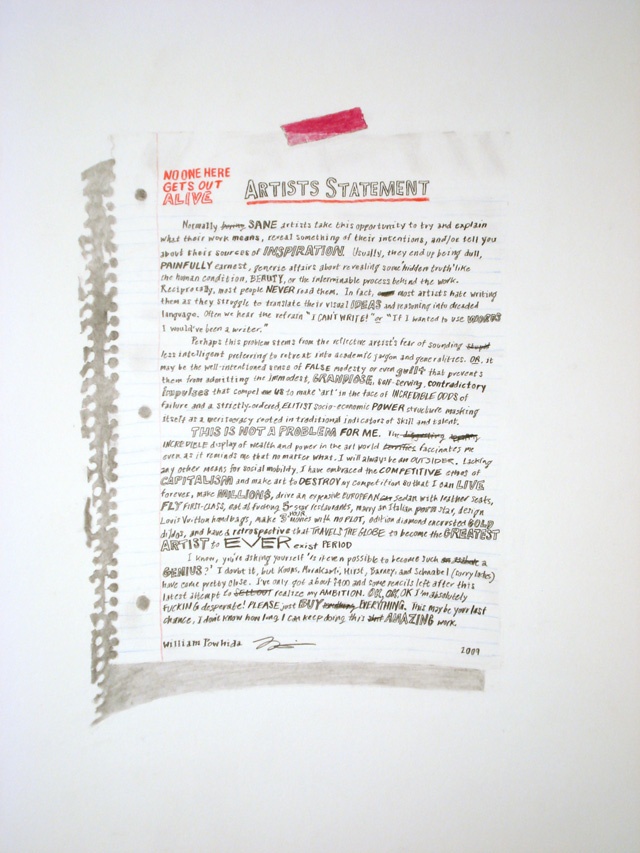

4. A short and specific personal narrative that relates directly to your art making. Autobiography has been a highly powerful tool for successful artists since the beginning of time. All art is, in some way, autobiographical and this story, told clearly, functions as a great first sentence or lede used to “hook” the reader. If you are making art for personal reasons, explain them because it deepens the meaning of your work and presents you as a unique individual.

5. An historical context explaining one or two influences on the work places it into a historical continuum. This shows that you understand what you are doing and why. It also may invite smart comparisons to your work.

6. NOTHING ELSE – save your feelings for your diary! The artist statement is a tool and cannot encapsulate the complexity of your work.

Other suggestions:

1. Do a studio visit with a colleague, artist, or critic and have them answer questions 1-5 for you and take notes. Let someone more objective than you put your visual work into words.

2. Read artist statements by artists who do work similar to yours. If they did a good job, write something similar.

3. Use a thesaurus – not for verbosity, but to make sure you don’t use the same word twice.