Be Our Guest: Houseguests, an artist-in-residency program at Evergreen Museum and Library, provides a meaningful way for artists to reinvigorate their practice. by Cara Ober

According to Benjamin Franklin, “Guests, like fish, begin to smell after three days.” While some of us enjoy a more extended stay, it is widely acknowledged that house guests can be both a blessing and a curse, and the success of a visit depends largely on the accommodations available and the graciousness of one’s host.

In the early 19th century, the Garrett family, of Baltimore’s historical railroad wealth, possessed ideal accommodations and an inclination toward entertaining. It wasn’t enough for the Garretts to collect fine and decorative arts and rare books and manuscripts—they wanted their home to inspire and nurture a new generation of artists. Their Gilded Age mansion, complete with a theater, carriage house, and library set on 26 acres of Italian-style gardens, was a comfortable and charming environment, so they started one of the earliest artist-in-residency programs in the country. The Garretts opened their doors to original artist projects, musical performances, theatrical productions, and experimental choreography and they converted their servants’ rooms into a “genius wing” of the house, for the artists to stay in.

Today the Garretts’ home is still full of the family’s extraordinary collections, including paintings by Modigliani and Degas and original glassworks by Louis Comfort Tiffany, but it is now known as the Evergreen Museum and Library , after it was donated in 1942 to Johns Hopkins University. The Garretts’ artist-in-residency program, known as Houseguests, still exists, and its unusually accommodating and mutable conditions continue to inspire, challenge, and support all types of contemporary artists.

This year’s residency was awarded to Tai Hwa Goh, a Korean-born printmaker who currently resides in New Jersey. Her installation, titled Lullaby, on view in the Evergreen Museum through May 27, is a testament to the organization’s willingness to allow total freedom to the artist, especially in a space filled with rare objects of antiquity. “The Evergreen Museum’s program was perfect for me to get myself motivated by their nature, architecture, and library collections to do experiments with my installation work,” Goh says.

Although the residency has no formal application process, contemporary artists are encouraged to submit a proposal and one artist, musician, or performing artist is selected each year. The program can include housing on the property, a stipend, access to all the collections, library, and support staff, and the opportunity to be inspired by the unique environment. Past projects have explored the Garrett family legacy, specific works of art in the collection, and the architecture and grounds, and include a wide variety of products.

“We don’t want to select someone who will be lost in the complexity of this place,” says James Abbott, the director and curator at Evergreen. “We want someone who can break away from their past practice, who is not too rigid, so that this residency is a chance to redefine their practice.”

Abbott says that ensuring an artist has “creative freedom” is paramount in the residency program: “The real success of this program is whether artists are reborn, and can reinvent selves and the space.” This year guest curator Cathy Barbehenn, a longtime museum member, selected Goh’s work from more than fifty applications from all over the world. Next year’s artist-in-residence is a choreographer (yet to be officially announced).

“Goh had been exploring handmade papers, contrasting the fragility of paper with the harshness of architecture, in modern, white-cube galleries,” says Abbott. “We thought her work would gain a whole different approach because of the historical architecture here. I think it works quite well, especially because it is more non-traditional than our typical art collection.”

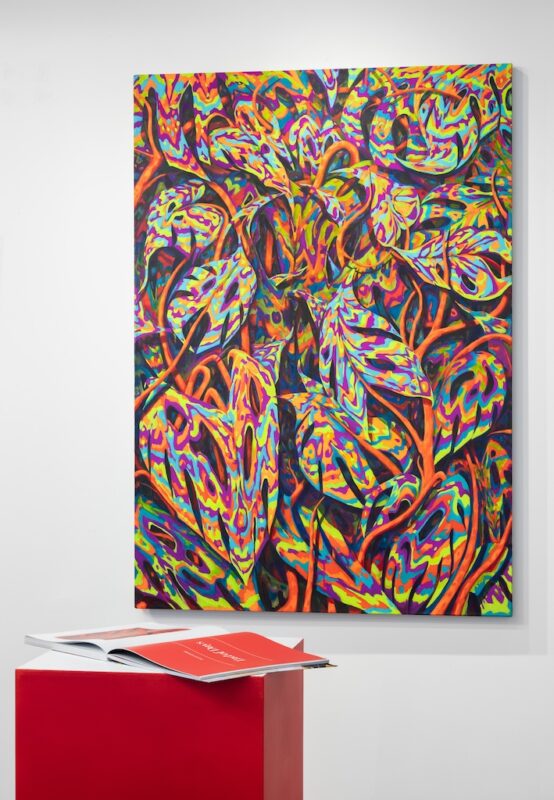

Once Goh had been selected, she had one year to complete her installation. To begin her research, she visited the library and collections. Then she stayed on the property for two weeks during the summer to continue her research and finalize her plan. “My work was inspired by the botanical images of the museum’s collection,” she says. “I was impressed by Aldrovandi’s Monstrorum Historia and Medical Botany. Those books gave me the chance to think about contrasts between vulnerability and curability, wound and heal, and anxious and lull, etc.” Goh took botanical images from the books back to her studio and used traditional printmaking techniques, like woodcut, etching, and silkscreen, on lightweight Korean mulberry paper. After printing, Goh hand-waxed the paper to make it pliable and translucent, and also folded, cut, flipped, and overlapped the prints in order to prepare them to be three-dimensional in their final form.

Goh decided to install a cascading, waterfall composition of the handmade papers on the main staircase of the house. A tall vertical, the staircase serves as a channel between the formal downstairs and the upstairs, private space. She titled the installation Lullaby because she intended her artwork to be a soothing transition. “As we ascend the stairs, we move from a formal, social space, which is filled with conflicts and interactions with others, to a private, quiet space, which comforts and smoothes the wounds. I intend to express the emotional changes through the space,” says Goh.

Experiencing Goh’s Lullaby is like “walking into a dream,” says Abbott. “I think the balusters, plaster cast cornices, [and] elaborate wainscoting can be intimidating to arts and artists, but I think she has done quite well in this environment. There is an interesting dialogue between her work and the architecture, and the historical references in the paper is so subtle, you have to look closely.”

Although many people visit the Evergreen property for parties and events, especially in the Carriage House, the museum is a still an under-utilized resource in Baltimore. “We are constantly expanding our offerings, and anyone who is interested in getting involved here can make a proposal,” Abbott says. “We work with students, curators, authors, performers, and contemporary artists.”

Just like Tai Hwa Goh’s cascading Lullaby, the Evergreen Museum strives to create opportunities for public and private dialogues between people, meaningful objects, and place. Unlike most historical museums, Evergreen strives to be inclusive, creating numerous invitations for people to experience it as their own.