What exactly are those casts of classical Greek masterpieces thinking, as they gaze down from the balcony of the Hall of Sculpture in the Carnegie Museum of Art at Pedro Reyes’ noisy Disarm? In the dignified quiet of the century-old hall (which was modeled on the Parthenon’s inner sanctuary), Reyes’ contribution to the 2013 Carnegie International initially feels out of place. An orchestra of computer-controlled musical instruments forged out of hundreds of confiscated Mexican weapons, it is both rough and raw, and materially divorced from its environment. The converted barrel supports and magazines are dark steel shadows in a world of graceful white marble; they’re heavy traces of violence in a realm of light and balance. Moreover, the brief staccato fragments of music that they spit out evoke the unpredictable rattle of street gunfire. What, we wonder, can Juárez have in common with the Parthenon?

Even as it’s asked, though, the question begins to answer itself. We suddenly recall that the sculptural program of the Parthenon was in fact a dense combination of ideal forms and raw violence: ivory Athena, heavily armed, aggressively looming over the cella. And then we notice, too, that Reyes’ work is not merely blunt, but also redemptive. Yes, museumgoers wheel from instrument to instrument as they come alive in turn, loosely evoking the flighty motions of a panicked crowd at a scene of violence. But as they do so, they smile in wonder and bemusement. Indeed, these instruments disarm in several senses: blunt instruments of violence are converted into percussive works of art, and onlookers find themselves peering curiously into the transformed barrel of a pistol. Rather like the Parthenon, then, the work transforms: it alters coarse weaponry, our sense of the inevitability of violence, and the very space in which it stands.

In that sense, Disarm might be seen as typical of this edition of the International, the oldest regular North American exhibition of global art. Curated by Daniel Baumann, Dan Byers, and Tina Kukielski, the show features the work of 35 artists from 19 countries, and displays a consistent interest in juxtaposition, repurposing, and dialogue. Granted, it is in some ways typical of recent trends in biennial design: co-curating has been modish for more than a decade now, and the International’s foregrounding of several outsider artists recalls the affirmative inclusiveness of this year’s Venice Biennale. Nonetheless, the International is rewarding. Tight in focus and relentlessly self-aware, it offers variations on the central theme of relationality while also turning its light on itself by interrogating the physical form of the Carnegie Museum and the history of the International as an institution.

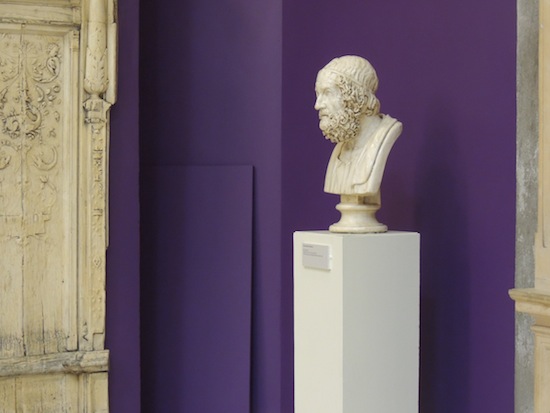

Several of the pieces, for instance, challenge and rethink the museum space. Gabriel Sierra, a thirty-something Colombian, tackles the Hall of Architecture and its celebrated collection of casts by repainting its frosty sage green surfaces a rich Byzantine purple and by introducing sculptural elements – a plywood plane; a boxlike frame – into the cluttered space. The subtle revisions quietly alter the effect of the room: familiar details suddenly read more dramatically against the regal backdrop, and the unexplained insertions prompt us to think about the casts in relation to both the conditions of display and a larger history of sculpture. Or consider Phyllida Barlow’s massive TIP, a sprawling forest of colorful wrapped wooden poles that extend dozens of feet into the air and that form a sort of jumbled barrier that zags through the museum’s entrance plaza. Chaotic but jubilant, the piece dwarfs Richard Serra’s adjacent Carnegie – no small feat – but also alters the mood of the plaza, which now reads as less sober, and more open to chance and play. And that’s almost certainly by design: nearby, on softer terrain, the curators have installed a bright yellow Lozziwurm, a pierced hollow piece of playground equipment designed in 1972 by Yvan Pestalozzi. Baumann has spoken of his desire to give the Carnegie’s exterior a less austere and more inviting aspect, and the twisting form accomplishes that. But even as the Lozziwurm softens the museum’s stone visage, the museum setting inflects the Lozziwurm – which we are now encouraged to read in art historical terms, as well.

This interest in reimagining the museum is a consistent theme in the International. You can see it, too, in the contribution of Transformazium, a Pennsylvania collective whose project involves a partnership with the Braddock Carnegie Library Association. Working with the library, the collective designed an Art Lending Collection: a corpus of about 100 artworks donated by a range of artists (including a number who participated in this year’s International). This display will be continued indefinitely, so any borrower with an active library card will be able to check out works or borrow a pass to the Carnegie Museum of Art. The museum, in theory, thus attracts a more diverse audience, while residents of the mill town of Braddock – the site of the first local library underwritten by Andrew Carnegie – enjoy an unprecedented access to formerly remote works of art. In short, the project pairs two institutions affiliated with Carnegie’s philanthropic activity, while also furthering his stated mission as a collector of art (“we shall do our best,” he once proclaimed, “to bring the rarest of those objects to them at home”). Home, in Carnegie’s logic, meant Pittsburgh; in this project, his phrasing assumes a more literal meaning.

This spirit of open self-redefinition also characterizes the curators’ reinstallation of the Carnegie’s modern and contemporary wings. Throughout those rooms, works shown in part Internationals and then acquired by the Carnegie are prominently identified with bold yellow placards. The result is a compelling, if abridged, demonstration of the considerable accomplishments of the International since its inception in 1896; it also offers an intriguing alternative history of modern art. As we come across old friends such as Rouault’s The Old King (shown in the 1939 International) or Fischli and Weiss’ The Way Things Go (shown in 1988), we’re prompted to think about their place in those past exhibitions, as well as in more standard historical trajectories. Indeed, the curators then develop this sense of historical self-reflectiveness explicitly in a newly designed gallery that offers an overarching history of the International. The materials quickly kindle further diachronic thinking: as we review images of the sprawling pieces that occupied the Hall of Sculpture in past years, Pedro Reyes’ work begins to feel surprisingly humble in scale, or notably devoid of a grandiose theatricality.

But the curators aren’t quite finished yet. Throughout the rehung galleries, we also find newly realized work: contributions to this year’s International that are placed in openly provocative juxtapositions with pieces in the permanent collection. The idea here, again, is not novel: fans of the Walters might recall a rather similar installation of works by Louise Bourgeois, in which her eerie, ambiguous sculptures unsettled comfortably pat readings of nearby ancient pieces. At the Carnegie, though, the curatorial decisions seem more pointed or even prescriptive. Lara Favaretto’s steel road plates, laid flat over soft layers of colored silk, are shown in a gallery of Impressionist paintings, and we nod – for the contrast between feathery delicacy and heavy industry is central to the works by Monet and Pisarro that stand nearby. That said, though, there are also fainter and more nuanced ripples that emanate from such a juxtaposition. The steel plates recall Pittsburgh’s industrial past, even as the silks point to the sleek wall surfaces of galleries erected in centuries past – and once more, we thus find ourselves thinking about forces of change over time.

Ultimately, then, this interest in confronted or juxtaposed histories is arguably the central trope of the International. A number of the included works are meditations on past moments or motifs, and the curators seem to enjoy extending the frictions, fault lines, and new meanings that result. A monumental photograph by Rodney Graham openly cites iconic images of Jean Cocteau and Asger Jorn. An intentionally sloppy, irreverent figure in plaster by Nicole Eisenmann reclines lazily against a pedestal, beneath a cast of a classical Amazon. But perhaps most typical, in this sense, is Summer Camp, a 2007 video by the Israeli artist Yael Bartana. The video pairs footage of the reconstruction, by nonsectarian volunteers, of a demolished Palestinian house with an abridged version of a 1935 Zionist propaganda film. History, our gallery guide informs us, thus begins to feel circular. But the curators have gone a step further: Bartana’s video is screened in a temporary space set up directly below a series of frescoes of local labor executed by John White in the early 1900s for the opening of the Carnegie Museum. Once more, we’re being nudged: to what extent, the curators ask, is labor ideological? And in what ways are building and permanence related?

Such questions, of course, can never be fully answered. But two other works in the International allow us to begin to develop a position, in response. The first is a misstep – an example, we might say, of a callow answer. I’m thinking of Wade Guyton’s repurposing of the museum’s coat checkroom, whose cabinets have been removed to yield a cursory lounge. Interventions involving such spaces are not new; three years ago, Janine Antoni slyly slipped fragments of an ethereal letter into the pockets of checked garments. And of course the idea of opening up spaces restricted gallery spaces associated with maintenance or labor has been familiar since Michael Asher removed an office wall in the Claire Copley Gallery in 1974. In this case, though, Guyton seems less interested in revealing a hidden logic than in making a nominally sociable gesture: a few scattered chairs seem intended to offer the possibility of rest. And yet the gesture is limited, or even violent and cynical: the scarred, ghostly space hardly supports restful meditation, and, given the poverty of the environment, we soon realize that Guyton has turned us into a captive audience for four of his own works, which hang on the walls. This is, finally, neither a true lounge nor a fruitful investigation of labor relations; rather, it’s a convenient conversion of museum space, by Guyton, into a vehicle of self-promotion.

Much more affecting, and more emblematic of the show as a whole, is a series of c-prints by Joel Sternfeld that hangs in the Hall of Sculpture, ringing Reyes’ work. Entitled Sweet Earth, the suite offers 29 views of diverse American experimental utopias: that is, of planned communities designed to yield a better social order. The structures are remarkably various; they range from urban to remote, and from ambitious to eremitic. In many cases, the buildings show their age. A geodesic dome slowly succumbs to the elements; a bus, in the woods, now feels like a monolith. To be sure, not all of the pictures are meditations on loss; in one memorable photograph, an evangelical builder smiles out at us with a remarkably serene confidence. Viewed cumulatively, though, the archive offers a moving testimony to the apparent fragility of optimism. The dreams of past dreamers are now often overgrown, or redeveloped, or dilapidated.

Or, at least, they can seem that way until we turn away from the images. As we do, we find ourselves face to face once more with Reyes’ converted weapons and their sporadic melodies. His project, too, is idealistic – and, in its faith that the materials of this world can be fashioned into something nobler, shares important ground with the classical figures who stand, above. Indeed, if we think about it, we realize that Carnegie’s museum also epitomizes this basic belief that the world can be bettered, and our lives improved, through effort. The process, admittedly, is never without friction, and the curators of this year’s International have worked hard to interrogate the purposes and potentials of their museum setting and of institutional logic. In the process, though, they have given us a show that creates numerous meaningful dialogues, and that inflects the very arena in which those dialogues take place. Sanctuary walls host images of decaying utopias near which refashioned machine guns play provisional melodies. Nothing, this show insists, exists in isolation – a point that even the Olympian figures above us have to acknowledge, as they look down upon us.

*Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.