An Introduction by Kerr Houston and Jennifer Watson

It is futile, perhaps, to try to identify the precise moment at which Western art criticism came into being. Was Plato the first art critic? Was Giorgio Vasari? Was Roger de Piles, who attempted to systematize the process of artistic judgment in the 1600s? Or should we point instead to Jonathan Richardson, who was apparently, in the 1720s, the first writer to refer to art criticism in print? Each figure, arguably, has a claim.

Perhaps it makes more sense, then, to simply note that each of these figures played a role in the gradual evolution of the genre that we now know as art criticism. At the same time, however, it does seem true that art criticism began to take shape as a coherent, self-conscious genre in the first half of the 18th century. Richardson, certainly, played a role in this process. But so too did a number of French observers who commented upon the Parisian Salon, a regular exhibition of works by members of the Royal Academy that took shape in 1737, and that persisted as an important venue well into the 1800s.

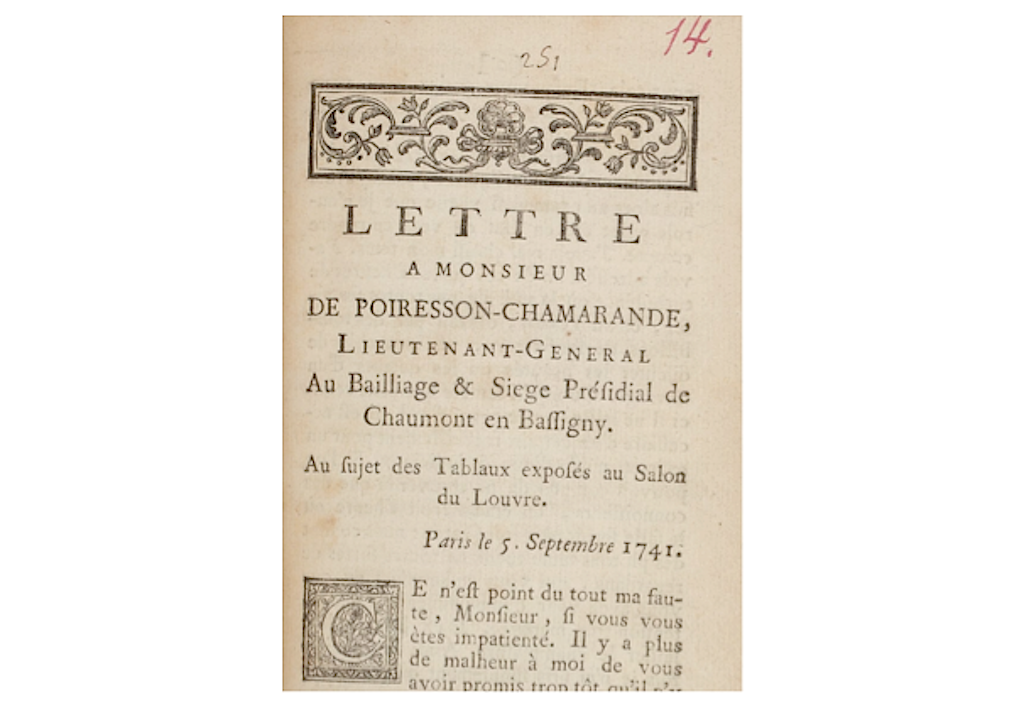

In this light, a printed text in the Bibliothèque nationale de France assumes a certain importance – for, as Thomas Crow noted in his excellent 1985 book Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris, it is “the earliest sustained commentary on the Salon that we possess.” Admittedly, there had been a few tentative responses to earlier Salons (including an acidic poem composed in 1737, by J.B.L. Gresset), and it is entirely possible that other comparably early written reactions simply do not survive. Nevertheless, the 1741 pamphlet, in which an anonymous author fills 37 pages with a varied commentary on that year’s Salon, assumes a certain primacy simply through its scale and level of ambition. Consequently, this “early art-critical preamble” (as Crow termed it) is in a sense an important ancestor of all subsequent art critics – of Diderot and Baudelaire, to be sure, but of Saltz and Smith, as well.

And yet, it has never been translated fully into English. Certainly, it has been republished in French, and Crow, in his book, translated portions of it. But he did so selectively, rendering only a few excerpts into English and even then omitting brief passages. Importantly, he did draw the attention of English-language scholars to the text, and it has since been discussed in passing by several writers, including Melissa Hyde and Paula Radisich. Clearly, then, the text holds a certain contemporary appeal, in addition to a clear historical significance. Which is precisely why we happily offer, here, the first full translation of the text.

A few further words of explanation might be helpful. The text takes the form of an epistle to a regional official from his affiliate in Paris – a conceit that allows the author to describe the Salon and its contents in helpful detail. In a basic way, the text’s structure reflects the organization of the exhibition; that is, the author moves sequentially though the rooms of the Salon, commenting on those works that catch his eye. And yet, his commentary is never limited to the art alone. Indeed, the author often remarks on the placement of specific works, even as he also conveys a marked enthusiasm for works that arrest the viewer, or cause him to momentarily ignore his surroundings. Moreover, the text opens with an extended set piece that focuses on the arrival of three self-important aristocrats who learn, to their deep surprise, that the doors of the Salon open early for no one. As a result, the pamphlet can usefully be seen as a piece of social, political, and institutional commentary, as well as a remarkably early example of a genre that was arguably in its infancy.

In translating the text, we have made a few changes that are worth noting. We have used modern rules of capitalization, and we have converted the original text’s many ampersands into more current phrasings. At the same time, though, we have retained the text’s frequent use of italics, which serve to draw the reader’s attention to particular works, artists, and motifs. Along the way, we have relied upon a range of resources. Especially helpful, though, have been Thomas Crow’s book, Louis Chambaud’s 1779 Grammar of the French Tongue, and various editions of Abel Boyer’s Royal Dictionary and French Dictionary. Finally, the authors would also like to thank Lisa Folda, for her assistance with several passages, and Cara Ober, for publishing our translation.

** Please note: This is Part 1 in a Series titled “Near the Origins of Art Criticism: An Original Translation of a Review of the 1741 Salon.” To read part 2, the actual translation, click here. To read part 3 click here.

* Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.

* Author Jennifer Watson is a PhD candidate in the history of art at Johns Hopkins University. She specializes in modern art and is currently completing her dissertation on Arman.