American Photographer Garry Winogrand at the National Gallery of Art by Kerr Houston

Most of them raise their heads and look up, up into the morning sky. Rather like Sumerian votive figurines, they stare into the heavens, at something that we can’t perceive: indeed, all that we can discern are a few gentle clouds and puffs of smoke. Only the clear, confident lettering on a dais gives us a sense of what we’re missing: the Apollo 11 rocket, rumbling into space and toward the moon. And yet, one woman seems to show no interest in the monumental launch. Instead, she coolly plants her feet in a solid stance and trains her camera at us – even as we view her, in turn, through a lens. Sandaled, graceful, aggressive, she is a modern day Artemis, and we, distracted from the purported central narrative, are her quarry.

The photograph is just one of more than 150 black-and-white images that comprise the American Photographer Garry Winogrand Retrospective, a rewarding show currently at the National Gallery of Art (through June 8), but it embodies several of the photographer’s most consistent interests: over the course of eight rooms, we repeatedly encounter images that offer variations on the themes of transience, peripheral detail, and confrontation. And yet, this show – the first major retrospective dedicated to the work of Winogrand (who died in 1984) since a 1988 MoMA exhibition – is not merely interested in reiterating familiar motifs in his work. Organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the National Gallery of Art, and curated by Leo Rubinfien, it’s more ambitious than that: rather, in the words of the hefty 464-page accompanying catalogue, it aims “to recapture the broad sweep of the photographs Winogrand made from the early 1950s through the early 1980s and to reveal for the first time the full reach of the picture of America that he created.”

That’s hardly a small task. For, while his career was not unusually long, Winogrand shot – especially toward the end of his life – at a remarkable pace, sometimes taking image after image from his moving car. And he was never a tidy archivist. Indeed, when he died – suddenly, of untreatable cancer – he left thousands of uncatalogued prints and undated contact sheets. As a result, any attempt to measure his career’s output is immediately confronted with a vexing question: what to do with that deluge of material?

Some historians have largely ignored it; for instance, John Szarkowski, an important early advocate of Winogrand’s, argued that much of the late work embodied a decline in quality. Rubinfien, however, takes a different tack by including a number of works never published or exhibited during Winogrand’s lifetime; indeed, more than sixty images in this show were printed for the first time. Those works, interestingly, are printed on a slightly larger scale than the images developed by Winogrand himself, and the result is arresting. Several of the new prints are deeply engaging, and the clever mode of display allows us to consider Winogrand’s output in a novel light, nudging us to compare his more canonical photographs with an alternative sampling of his work. As Sandra Phillips puts it, in the catalogue, “There is a new story to tell here, and new pictures to see.”

Or, to put it differently, we can begin to think closely about the artistic portrait that is being offered to us. For there’s no doubt: Rubinfien does offer arguments in this show. That’s most evident in the opening wall text, which casts Winogrand as a heroic figure in clichéd terms that evoke early frontiersmen (he roams; he takes sweeping portraits; his career is epic), and argues that he was able to give form, in his work, to the elusive Zeitgeist (his best work “exposes some deep current in American culture”). But it’s also visible, in more muted forms, in the show’s layout.

The coy juxtaposition of photographs of women and of animals in zoos, for instance, feels like a nod to longstanding complaints about Winogrand’s attitudes toward women. At the same time, though, a fascinating 15-minute video of a 1977 question-and-answer session allows the artist to speak for himself, and Winogrand’s irreverent, earthy candor is immediately evident. Additionally, several vitrines of accompanying materials explore connections between his family life (he was married three times) and his work. And then there’s the catalogue, whose accessible essays position him as an important observer of changes in the American social and physical landscapes (we can trace, for instance, the emergence of suburban culture and an erosion of faith in American political integrity).

Ultimately, though, other, quieter patterns emerge as well. Like many photographers, Winogrand was fascinated by the consequences of framing and cropping. In his earliest work, done for a variety of magazines, his compositions are often relatively conventional. With time, though, he became more interested in the way in which a print can propose, merely through inclusion and exclusion, alternative priorities. Or, as he put it, “When you put four edges around some facts, you change those facts.”

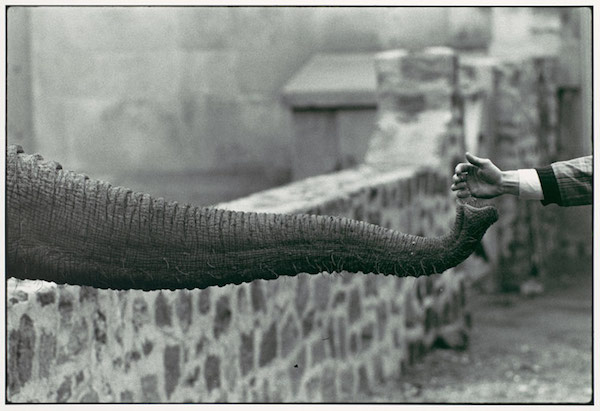

Take, for instance, his well-known Hand Feeding Elephant Trunk, Zoo, a 1963 work from a series of photographs taken in zoos: here, the careful cropping turns a playful, offhanded moment into an implicitly epic encounter: the image acquires the gravitas of Michelangelo’s Sistine Creation of Adam. Similarly, a 1968 photograph of a white hand extended toward an African-American beggar suggests, as a placard observes, an anonymous coldness: charity, in such a work, is faceless and almost mechanical.

By cropping, Winogrand often also positioned us, as viewers, in an ambiguous or frustrating position in relation to a seeming narrative center. Again and again, we don’t see the subject at which pictured subjects gaze; we can’t completely reconstruct the storyline, or we don’t get the joke. In a 1965 photograph, a crowd surges toward us, restrained by a flimsy police barricade. Are we in trouble? Are we in the immediate presence of a celebrity? It’s not clear – just as it’s not clear, in a 1960 photograph, what happened to the man who lies on the sidewalk, near a pool of coagulating blood. Such photographs offer us facts, yes, but only part of the whole picture; in a word, they abstract, and they remind us in the process that narratives too are constructions that depend on a certain process of framing and editing.

There is a tension, then, in many of these photographs between what happened and what we see. Clearly, too, this tension intrigued Winogrand, who often referred to it in speaking on his work. In the video, for instance, he asks, rhetorically, “Is the photograph more dramatic than what was photographed?” But his use of the term dramatic is also interesting, as it points to a longstanding interest in theatricality, and in the accompanying ideas of performance and artifice. Winogrand was often drawn to subjects and sites that are naturally theatrical: to press conferences, for instance, and airport waiting lounges, and football fields and even strip club stages. “The world is a place,” he once claimed, “I bought a ticket to. It’s a big show for me, and it wouldn’t happen if I wasn’t there with a camera.” And so his camera becomes a means of effecting, as well as recording, the ongoing performance.

The resulting images can be celebratory, or even comic, but they can also be heart-wrenching and pathetic. As Rubinfien told the New York Times, in speaking of the poles encompassed by Winogrand’s work, “One side is a great exuberant warmth, a love of the plebeian energy of American life, and the other side is a persistent despair, that it’s all out of control and that it will end up badly.”

Generally, Rubinfien argues that Winogrand’s later images embody that sense of despair more consistently, but I’m not quite convinced: even in the earlier photographs, New York City often reads as an essentially hostile environment, in which small moments of grace offer a brief respite from cold architecture and bleached light. Several of the protagonists in these photographs, too, have suffered serious injuries. Winogrand, you might thus say, was always alert to the fragility of human existence: after all, the play always ends, and the curtain always falls. Thus, a cowboy strolling through Dallas in 1964 looks more like a puppet than a gunfighter; his limbs feel wooden, and his outfit almost ludicrously out of place in the acres of surrounding concrete.

Then, too, there are those teeth. Has any visual artist ever featured bared teeth so regularly and prominently? As we stroll through the show, we see teeth revealed in wide grins and in ungainly guffaws; we see them clearly in impolite shrieks and in buoyant shouts. A bear’s teeth gnaw at the sign that is affixed to the bars of its cage. And, slowly, we begin to sense a more ominous overtone: teeth, revealed, imply a hint of hostility, or a cessation of niceties. Lips pulled back imply a dissolution of carefully constructed facades. Thus, even a woman laughing joyfully and freely acquires, when photographed by Winogrand, a certain danger: for, as an accompanying placard points out, her spirited smile is juxtaposed with a headless mannequin and a partly devoured ice cream cone. Teeth can suggest release, but they can also tear, and dissect.

In this sense, Winogrand was never simply a figural photographer. No doubt, people fascinated him, and a mere six of the works in this show eschew human subjects entirely. And yet, it would be hard to call many of the works optimistic. More often, Winogrand’s subjects seem frail, vain, and ultimately isolated. They try, to be sure, to connect, and enjoy slivers of transcendence, but are often undermined by the larger context. An appealingly goofy man bearing a thoughtful welcome sign in an airport lobby is dwarfed by the sleek architectural supports that gracefully rise above him. Three Californian beauties who glide, like the Three Graces, along a Los Angeles sidewalk in divine light, suddenly seem like naïve innocents in a vanitas painting when we notice the slumped man in a handicap to their right.

Such photographs are closer in tone, you might say, to Hopper and Francis Bacon than to Rockwell and Henry Moore. Indeed, some of them feel almost like Calvinist rejoinders than exercises in empathy, and in fact Winogrand generally declined to forge connections with those whom he photographed. Such an approach is bluntly implicit in some of his works, as in a 1968 photograph of a young woman in an elevator: trapped in the tight space with Winogrand’s lens, she has the look of the hunted. His interest in her as a potential image, rather than as a person (Winogrand often said that he photographed to see what subjects that interested him would look like as photos), is palpable. Or, as he put it, in 1977, “I don’t get to know people when I’m photographing. When I make a shot, I’m gone.”

And now Winogrand has been gone for 30 years. This notable show, though, does a good deal to restore our sense of his importance, and potential relevance. Clearly, photography has evolved radically since his death, and in several ways Winogrand seems to belong to another era. Indeed, part of the pleasure of the show depends upon its rich evocation of that time: from the car fins and cafeterias that populate his images to his typed Guggenheim fellowship application, these are images rooted in a past that no longer exists. Or, at least, that exists in altered form – for in fact his alertness to the manufactured aspects of media events could be called prescient, and his interest in the weird marriage of awkwardness and grace that characterize much of life feels simply true.

Things change, then, but not entirely. In a terrific passage in a 1988 essay, Szarkowski wrote that Winogrand “would keep shooting and moving, revising the framing and the vantage point, and re-editing the component parts of his subject matter, hoping for an instant of stasis – a resolution so gently provisional that it would scarcely seem to halt the efflorescence of change.” Provisional stasis, then, or an epic, unresolved quality: you can choose the curatorial term that you prefer. Regardless, it’s clear that Garry Winogrand continues to deserve and reward interest and attention, across the decades.

The American Photographer Garry Winogrand Retrospective is up at the National Gallery of Art through June 8, 2014.

* Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.