On one of the first hot days of the summer, I approached K-Town studios from an alley paralleling Howard Street. It led past a soup kitchen, deserted parking lots, a used-car concern, and some battered municipal buildings. The building itself was unremarkable: standard brick façade, plain windows, tangle of transformer boxes and power lines snaking off the telephone poles in back.

Mina Cheon, a painter, new media artist, and MICA professor, met me on the third floor. She shares the space with her husband, Gabriel Kroiz, a practicing architect and the Program Director of the undergraduate architecture program at Morgan State University. They bought the space in March after a short search for a new studio for Cheon.

“I looked on the web. This came up. Asked our friend and realtor Ben Middleman showing us houses to show us this one too. We never made it to [the houses.]”, Kroiz told me, laughing. A little under 5,000 square feet, on three floors, the building had most recently been commercial offices, housing social services and medical practices.

Located on 22nd Street, K-Town Studios takes its name from the surrounding Korean community. Comprising a little over six square blocks, Korea Town sits along Maryland and Howard Streets, just north of North Avenue. Wedged between Remington, Charles Village, and the Station North Arts District, the neighborhood has rental apartments, a handful of Korean restaurants, and a bundle of social service providers. Close enough to bike to MICA, and near a cluster of hip bars, the area has been attracting young artists on the hunt for low rent.

“There seems to be an ability for this neighborhood to serve different communities,” says Kroiz. “Artists don’t take offense to [clinics]. Heavy social services usage is in the morning in the neighborhood, and the heavy entertainment use is in the evening.”

Cheon is a Korean-born American resident. Each summer, she returns to teach in Seoul. “I came to Baltimore in 1997 to study with Grace Hartigan,” she told me. “Then I met Gabe, got married, had children, started teaching at MICA, and stayed.”

Living in Fells Point at the time, Cheon eventually earned three graduate degrees over a ten-year period, while Kroiz built a solo practice that focused on residential work, restaurant interiors, cultural spaces, and even artist studios. In search of more space for their young family, they moved to Bolton Hill. In 2008, Kroiz started full time at Morgan, and Cheon needed some space to work outside their home. “I started by working at a friend’s space where Gabe put in the electricity, put in the lights.” The studio was rough around the edges but enabled a new period of productivity.

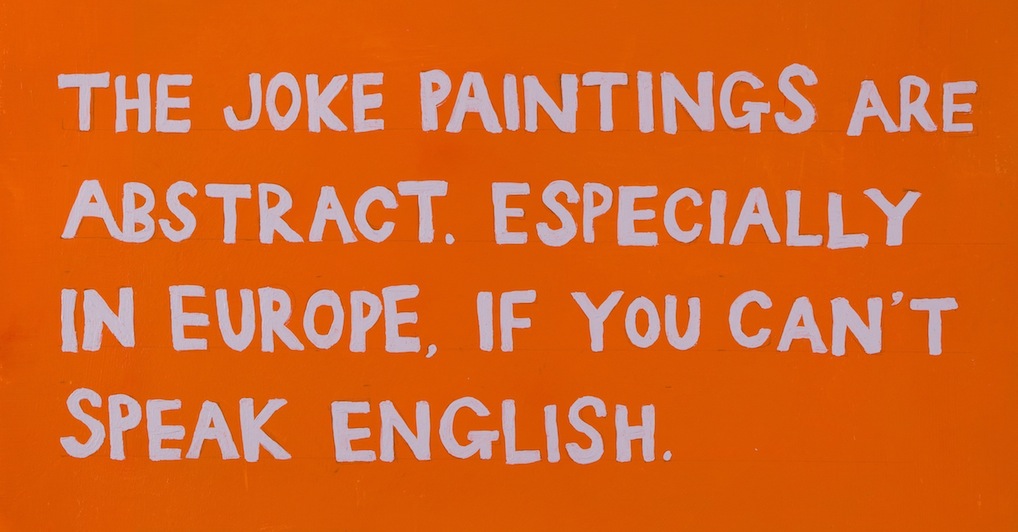

Her work, which she calls “Polipop,” short for political pop art, inverts propaganda tropes, commercial imagery, and political advertising in response to contested geopolitical sites. Of special interest to her is the DMZ between North and South Korea and contested islands in Asia.

“The way North Korea is viewed in America is totally skewed and there’s no sympathy,” Cheon says. “But as a South Korean I believe we’re still the same people.” One of her recent pieces revolved around Choco·Pies, which are the most heavily-smuggled item across the China-North Korea border. The manufacturer Orion donated hundreds of boxes, which were stacked all over the studio. Visitors to the gallery were encouraged to taste one, mapping the conflicting senses of sweetness, loss, and isolation that animate the Korean conflict.

For Kroiz, the Korean connection has had an expansive effect on his work. “As an architect, it’s been totally eye-opening to have that much access to a culture and a different way of looking at things,” he says. Over the summers, he also lives in Seoul part-time, co-teaching with Cheon and working in collaboration with local architects. In some ways, his status as a cultural outsider has contributed to the success of his Korean projects.

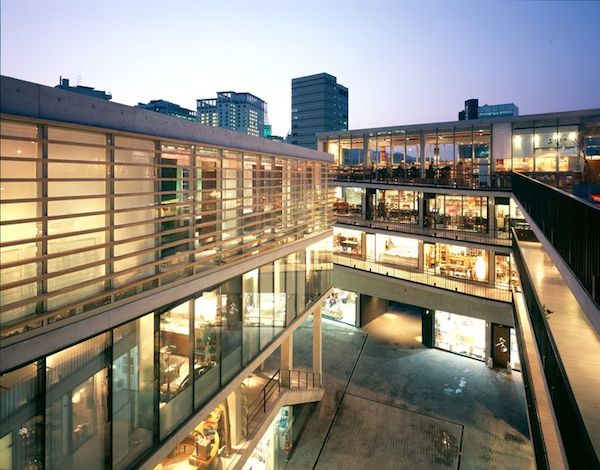

“I guess if you’re a foreigner, you’re not into the trends. He’s just looking at the site and responding,” says Cheon. For the Ssamziegil Shopping Center, completed in 2004, Kroiz recreated the traditional winding, shop-lined alleys of old Seoul within a spiraling vertical structure. Since there are no separate floor plates, hierarchies (and rents) are flattened out while still maintaining a vibrant density. Shoppers end their journey on the roof of the building, with an expansive view of the mountains north of the city.

The couple’s personal cultural exchange cuts both ways. “I’ve converted. I’m engaging in Baltimore in the Jewish community that Gabe [grew up in],” says Cheon. “And I’m a better Korean cook than she is,” added Kroiz, laughing. Together, they’ve taken that multi-modal approach to cultivating community within K-Town Studios. Most of the spaces are occupied by recent art-school grads, with a collective slated to move in to the larger first floor space as soon as some repairs are complete.

“As educators, we’ve always surrounded ourselves with students, so this just feels like an extension of that in a way,” Cheon says of their tenants. “We’d like it to be a cultural hub. So when people come to Baltimore, curators coming in from outside, this is a stop to make.”

A tour of the building revealed a broad cross-section of emerging art in Baltimore. Lee Boot, a professor at UMBC and multimedia artist, anchors the second floor. Dave Eassa, Colin Foster, Travis Levasseur, and Pete Razon round out the smaller individual studios. On the first floor, Katie Duffy and Ali Seradge will work in a collective studio and gallery space. Cheon and Kroiz are relentless cheerleaders for their tenants, mentioning upcoming solo shows and publications as we poked our heads in the studios. They are excited about the possibilities of studio open houses, group shows, and talks.

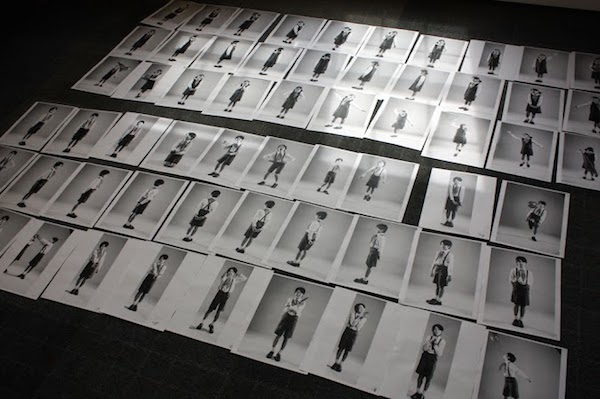

Cheon is taking advantage of the new space to pursue a new line of work for a new summer show at the Trunk Gallery in Seoul, Korea. “I returned to painting as a North Korean artistic persona the last several years. Her name is Kim Il Soon, she’s a social realist,” Cheon said. Worked out from photographs of herself and her children, the paintings are densely detailed, with a refined surface. Each one takes more than 100 hours to produce, a process that echoes and meditates on North Korean labor practices.

Kroiz works in the next room, surrounded by boxed blueprints. “In general it’s in fair shape. The electric is coming together, the roof needs to be coated, we need heating in by winter,” he says, sketching out the next round of improvements to the studios. They are planning a grand opening and show in September, when renovations and summer travels are finished.

Cheon and Kroiz haven’t thought much further into the future than the fall. After the studio tour, they walked me back out into the muggy afternoon, pointing out other landmarks up and down the street. Around the corner, across the alley from the back corner of the building, was a small weedy lot boxed in with chain-link. “Maybe next year,” they told me, “we could wedge in a small urban farm.” As I headed back up the alley, wet from a brief rain, I could almost see it.

Author Will Holman grew up in Towson and studied architecture at Virginia Tech. Since then he has poured concrete, built cabinets, studied low-income housing, taught carpentry, and worked as a studio assistant. He recently returned to Baltimore to work as a Fellow for the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation. Find him on Twitter @objectguerilla. Views expressed in this article are his own.