Kerr Houston reviews History Doesn’t Laugh at Goodman Gallery

When Hank Willis Thomas first showed his work at the BMA in 2009 (in conjunction with a residency at Johns Hopkins), the museum called him “a rising star in the art world, with works shown at numerous exhibitions at national and international venues.” Well, amen to that: five years later, Thomas has assumed a clear place in the artistic firmament, with recent solo shows in Cleveland, Berlin and, last month, Johannesburg and Cape Town, at the sister branches of the influential Goodman Gallery. But of course such global success can present challenges – especially for an artist such as Thomas, whose work has traditionally relied in part upon sensitive archival research and acute deconstructions of the intersections of race, gender, and commodity. How to maintain or extend, in other words, the sharp edginess and provocative specificity that characterized his early practice, as he jets between three continents?

Let’s begin by acknowledging – vigorously – his right to create, on his own terms, in South Africa. Sure, you can hear the whispers if you choose to: what exactly allows a 38-year-old American to work with the complex and contested visual culture of apartheid? And yet such concerns are relatively easily brushed aside. After all, Ernest Cole (now one of the most celebrated apartheid-era photographers) left South Africa for the United States in 1966, and sought out evidence of institutional racism in the American south. Surely the same formula can work, more or less, in reverse. Then, too, there’s the fact that Thomas created a new body of work for his show at Goodman – a fact not lost on the South African critic Michael Smith, who applauded Thomas for producing a tailor-made show, instead of merely shipping a few works across the ocean. Thomas, in other words, was actually in South Africa, researching, developing, and installing his show, and even finding time to speak with a group of MICA students in Cape Town for the summer. This was not work made remotely.

But what, then, of the work? Thomas’ show, History Doesn’t Laugh, is emphatically historical in nature: the 24 objects, prints, and installations shown in Cape Town, for instance, are motivated by (and often openly appropriated) classified ads, political logos, magazine graphics and photographs made in South Africa before the openly democratic elections of 1994. In a general sense, then, Thomas’ work can be seen as yet another example of a lively post-apartheid artistic interest in memory and reflection. On a more specific level, though, Thomas’ recent work seems centrally interested in two more particular themes: in the construction of black South African identities in mass visual culture, and in the intersections of radical politics and 1960s artistic strategies. Fair enough – and the end result is certainly coherent and occasionally beguiling. But it also feels, at times, willfully tidy or limiting. South African history, here, is arguably simplified: richly salient icons of South African visual culture are stripped of much of their complexity, and removed from layered contexts. They are pressed into specific duties, and are efficiently commodified. Even as Thomas draws attention to his sources, in other words, he also flattens them.

We might turn first to An injury to one is an injury to all, a nearly meter-wide magnified political button (complete with an unwieldy pin on its back) emblazoned with the logo of COSATU, the South African trade union congress that played a major role in the dismantling of apartheid. Or, at least, something very close to the logo – for in fact Thomas has removed the organization’s slogan from its usual location on the pictured wheel and converted it into a title for his work. That displacement is notable, for the artist now assumes the role of speaker; the pictured workers, by contrast, toil and gesture in an empty verbal field. At the same time, the object’s scale removes it from the realm of the utilitarian, converting a sign of personal political affiliation into a monument. And, of course, into an artwork.

Indeed, the meticulously clean surfaces of Thomas’ piece, which is made of fiberglass and aluminum, recall the synthetic resins and glossy sheens of finish fetish artists in 1960s Venice Beach. Think, for instance, of John McCracken’s planks, which were at once paintings and objects – and were rooted, like Thomas’ button, in sign culture. Brightly immaculate, devoid of the signs of facture, and celebratory in size, Thomas’ button will never be donned, or nicked. Instead, it is destined to play a more lapidary role: the call to arms, here, has been muted and coolly converted into a saleable object.

Not that Thomas is insensitive to the logic of commodification. To the contrary: some of his early works offered acidly effective commentaries on the position of black American athletes (in his 2006 Branded series, for instance, he digitally burned the Nike logo onto the body of a black male model, evoking a fraught convergence of slavery, profit, and entertainment). And in South Africa, as well, he soon encountered a band of visual evidence linked to the marketing of black body images: small advertisements, that is, that ran in True Love magazine decades ago and that hawked Afro-American mail order products such as stretch mark cream and weighted wristbands. In Cape Town, Thomas enlarged fourteen of these, presenting them as prints in a hanging that loosely recalled the dense layout of the back pages of a magazine. Collectively, then, the pieces thus suggest the insistent vapidity of crass capitalism: in a South Africa riven by racial difference and violence, was there really ever a pressing need for invisible body wraps? And yet, several of the images quietly allude at the same time to cultures of conflict and racial aspiration: inserts for Protect-O-Sticks and fake pistols point to a sensed need for security that is still visible throughout the country, and an ad for hair conditioner (“Have you always wanted thick healthy shining hair?”) acquires an almost tragic poignancy, given the history of hair tests in the racial classification systems of apartheid.

It’s worth noting, though, that Thomas has severed the advertisements from their original context in several senses. Hung in a gallery, the ads are no longer mere allusions to products, but have become products themselves: they are, in a sense, the items for sale. Furthermore, on the walls of a white cube, they no longer have to compete with the spicy features and photographs of True Love (in whose pages the ad for a varicose vein prevention would have made an entirely different sense). Thomas, in other words, seems uninterested in the jarring juxtapositions of content and advertisements that can characterize magazine and newspaper layout (and that was once analyzed by David Levi-Strauss, in his 1987 essay “Photography and Propaganda”). Such juxtapositions, though, have a distinct place in the history of apartheid-era imagery. Take, for example, Jürgen Schadeberg’s 1952 photograph of a young Nelson Mandela seeking news of the Defiance Campaign Trial in the paper – and flatly ignoring the classified ads that line the left page. Or, if you’re feeling bold, have a look at Peter Magubane’s image of dead bodies felled in Soweto in 1976, and covered with newspaper. “The end of nervous tension,” an advertisement in the paper promises, as an inert hand rests nearby. Such photographs remind us that while ads may have constituted a constant presence in the visual landscape of apartheid, they were also granted particular meanings (or rendered particularly banal) by a range of contexts.

Perhaps the most memorable pieces in Thomas’ Cape Town show, though, were three sculptural works based on famous apartheid-era photographs. The basic idea here – converting a portion of the content of a photograph into a three dimensional installation – is relatively unusual, but hardly unprecedented. Think, for instance, of the Marine Corps War Memorial, which was based on the iconic photograph of flag-raising by Joe Rosenthal. Indeed, there is now even a small class of South African instances of the genre, ranging from a bronze realization of Sam Nzima’s photo of a dying Hector Pieterson (at a mall in Soweto) to a monumental conversion of Bob Gosani’s photo of Mandela boxing (in Johannesburg). In any event, Thomas chose images by three different photographers – Ernest Cole, Eli Weinberg, and Catherine Ross – and then effected three-dimensional renderings (in various materials, including bronze, copper shim, and aluminum) of figural details in each.

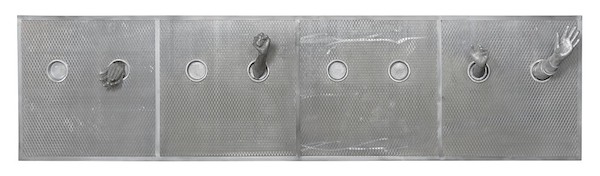

Certainly, the resulting sculptures are potent. In Raise Up, Thomas gives us the heads and arms of ten of the thirteen black miners pictured by Cole as they undergo a humiliating medical examination, in the nude. In Die Dompas Moes Brand! (The Passbook must Burn!), the hands of protestors boldly consigning personal papers to the flames protrude from the gallery walls – and stand above an actual pile of ashes on the gallery floor. And in A Luta Continua (the title is a pan-African slogan, and refers to ongoing struggle), we see the hands of demonstrators poking out of the portholes of a police van as they are driven away from the South African Supreme Court during a 1992 protest. In the process, then, revealing moments in South African history – and celebrated entries in the photographic record of apartheid – are given solid form. John Berger once counseled viewers of a collection of South African struggle photographs to “go close. Imprudently close.” Here, Thomas’ sculptures seem to propose something similar: indeed, it’s tempting to reach out and to grasp the hand of one of the detainees in the police van.

That said, however, it’s also vital to realize that Thomas is once again working selectively; he is both editing and imposing his own interpretations. His decision to focus on gestures apparently led him to jettison much of the rest of the original photographs – and the resulting loss is considerable. Cole’s photograph of the miners, for instance, pictures a row of papers that stand behind each man – and that implicitly complete their dehumanization, converting them into mere data in the larger ledger of labor. Similarly, Weinberg’s photo of the pass burning includes a stirring juxtaposition of shod and bare feet, suggesting that the gesture of protest transcended social class. The hands in Thomas’ sculpture, by contrast, are anonymous, and dully metallic. But if Thomas’ work thus omits details, he is also actively managing the imagery. Consider Raise Up: for one thing, the title represents a radical reworking of the clinical but clearly aggrieved caption that accompanied Cole’s image when it was first published (“During group medical examination the nude men are herded through a string of doctor’s offices”). Paired, by contrast, with Thomas’ title, the outstretched arms of Cole’s miners cease to become signs of industry’s power to control the body of the worker. Rather, they are converted into a sign of insurgence; they are given covert agency. A debasing procedure yields to an exhortation to rebellion.

Is that fair? Certainly, such a retitling is suggestive. But it also suggests a willingness to view the past loosely that belies Thomas’ own stated views about archival materials. “Archival images,” he told Okay Africa in a recent interview, “are like time capsules. They do function as windows into the past.” In sculptures such as Raise Up, however, the image is treated more aggressively: it is a ground for a revisionist reading, and offers the possibility of active modification. And yet, such an approach can be problematic. After all, as Darren Newbury has argued in Defiant Images (a history of apartheid photography), “photographs are not simply raw materials for creating histories…; they bring with them their own histories.” Indeed: and not only photos. I think, too, of the cast-iron bootjack included in Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum. A figure of a black woman with her legs splayed, the bootjack embodies a violently racist iconography – but it also retains, associatively, the dirt of every shoe that scraped across it. Part of the force of Wilson’s presentation lay in the realization that he didn’t have to edit or retitle the historical object: simply presenting it was an indictment, in its own right. If historical objects are windows into the past, then, they are often smudged or sullied apertures. They are, in a word, used. And while Thomas’ appropriation of Cole’s photograph now forms a part of its use, as well, it seems to do so almost unreflectively. The conceptual artist is the last to join the game, for the archival object is never, in fact, pristine.

In an essay on reproductions of photographs by Timothy O’Sullivan, Rosalind Krauss once argued that the original works and the derivative photolithographs “belong to two separate domains of culture, they assume different expectations in the user of the image, they convey two distinct kinds of knowledge. In a more recent vocabulary, one would say that they operate as representations within two distinct discursive spaces, as members of two different discourses.” Such an analysis offers a useful means of thinking about Thomas’ photo-based sculptures, as well. They are, for instance, works of art, where their sources were often conceived primarily as evidence of unjust practices. Relatedly, Thomas’ works are retrospective, rather than documentary; they depend, that is, upon a past, instead of trying to convey a present. In the process, too, they advance a thesis about that past: they accent, in their emphasis upon united gestures and their repression of narrative detail, a strain of unified political resistance. And, finally, they are undeniably theatrical. They grant tangible form to a script that is otherwise resolutely two-dimensional.

That’s theatrical, then, in a melodramatic sense, rather than in the phenomenological sense in which the term was used by Michael Fried in 1967. And yet, there are ways in which Thomas’ sculptures do evoke artistic conversations of the 1960s. The framed hands in A Luta Continua, for instance, distinctly recall the eerie disembodied heads and feet in some of Jasper Johns’ early target paintings. And the side of the police truck itself, cast here as a slab (rather than viewed from an angle, as in Ross’ original photograph), quietly evoke the work of early Minimalists. We intuit, as with certain works by Robert Morris, the form’s gestalt without seeing all sides at once. Combine those aspects with the evocations of McCracken’s work and the Pop-like magnification of advertisements and comic panels, and we seem prompted to think in terms of Sixties discourses.

But why, it’s worth asking, that decade in particular? In South Africa, after all, the Sixties represented a relatively dark time, from the point of view of the liberation movement. The leaders of the African National Congress were largely behind bars, and the national economy was thriving. Artists such as Cole consequently felt little optimism about the future – a point clearly evident in his 1967 book House of Bondage, which ended with an image of a tribal leader asleep, a Bible on his face, and a bleak caption referring to the dispossession of Africans (“When the Europeans came, they had the bible and we had the land. Now we have the bible and they have our land”). But of course 1967 meant something very different in the States: among other things, an active and largely empowered civil rights movement. Thinking about South African visual sources from the period in terms of parallel American idioms, then, allows Thomas to recast the struggle against apartheid. That fight becomes, here, part of a global conversation. And the resulting source images are changed, through a variety of alterations, into emblems of uplift, rather than degradation.

Again, Thomas is far from the first person to reflect on South Africa’s past in this, the twentieth year after the election of Nelson Mandela. And images, to be sure, have an important role to play in this process. Indeed, that’s one of the assumptions underlying the blockbuster photography show Rise and Fall of Apartheid, which was curated by Okwui Enwezor and Rory Bester and which recently arrived in Johannesburg. But in this context we might also recall the photographer Omar Badsha’s claim that “Images of defiance, images of struggle… or past struggles, became a way of reviving the memory of people and the movement, and talking about the movement and its history and its role.” Thomas seems in turn to agree: in speaking of his South African show, he argued that “There are works of commemoration, but there are also works about moving forward, or at least rethinking the past.” Okay. But can you sense the slight hesitation, or qualification, in his assertion? These may or may not, he seems to realize, ultimately be works about moving forward – but they are certainly concerned with the past.

In Defiant Images, Darren Newbury tells a humbling story about the course of his research. In 2004, he traveled to the township of Mamelodi to interview Geoff Mphakati, who had been a close friend of Cole’s in the 1960s. As the two men discussed House of Bondage, Mphakati asked Newbury what he had seen when he entered Mamelodi, or in other townships in South Africa. “This reversal,” Newbury later recalled, “caught me by surprise, and my stuttered response, that I saw people living in difficult circumstances, seemed to both of us completely inadequate.” Hank Willis Thomas’ show is certainly not, in any sense, inadequate: rather, it’s a nuanced and visually impressive response to a range of historical materials. But, as Michael Smith has argued, it’s slightly toothless. “What seems to be missing,” wrote Smith, “is a sense of wit, of incisive critique around the way these images operated and are still deployed.” The show has little to say, in short, about the present. Instead we’re left, again, thinking about history.

To be sure, you could argue that when we look at photographs we’re always thinking about history. As Susan Sontag observed in On Photography, photographs “turn the past into a consumable object.” But as Thomas converts photographs, in turn, into consumable objects, it’s also worth keeping a further observation of Sontag’s in mind. Photography, she contended, “does not simply reproduce the real, it recycles it – a key procedure of a modern society.” And if that’s true, then we need to think about the specific contours of such a process. How we recycle, in other words, matters.

History Doesn’t Laugh is Hank Willis Thomas’s first solo exhibition at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. The exhibition ended on June 28, 2014.

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.