A Visit to Kyle Bauer’s Studio by Dwayne Butcher

Kyle Bauer has just finished a three-year residency Baltimore Clayworks. He moved to Baltimore after receiving his MFA from Louisiana State University. Bauer’s work is an exploration of both traditional and alternative ceramic processes that are realized within the context of mixed-media sculpture. He has had recent exhibitions at School 33 Art Center, The Walters Art Museum, Arlington Art Center, and Maryland Art Place.

I visited his new studio in Greektown where we talked about ceramics, what it takes to be a real artist, beer, living in the South, the Mississippi River and the I-55 corridor. Here is part of that conversation.

Dwayne Butcher: You recently finished up a three-year residency at Baltimore Clayworks. How did you end up there?

Kyle Bauer: During my final year of graduate school, I decided that I was not ready to go right back into academia. I wanted to be a teacher who can provide real world experience on what it takes to be an “Artist.” I didn’t want to be another professor whose studio working life exists in only academia, so I did some research and applied to five different residency programs: one in Montana, one in Philly, one in NY state, another in Houston, and finally here in Baltimore. I chose these places because of their reputation for representing top talent and opportunities both during and after the residency period. I received one rejection letter after another, and I was beginning to think nothing was going to pan out. Baltimore Clayworks called the next week, and the rest is history as they say!

DB: What did you do while you were there? Were there any requirements from Clayworks?

KB: The first six months were slow; it took some time to get a rhythm going again. I had a new studio with new rules and a new job as a security guard at the BMA, it just took time to figure out how to get it going again. I never stopped making, but I just didn’t make anything worth saving. I spent a lot of time compiling images, drawing, building my website, rewriting my artist statement, editing my exhibition proposal packet, and applying to everything under the sun. I had to flush out the bad to get down to the good. My thesis year of grad school really took a lot out of me. There were the highs of finishing, the low of having my written thesis rejected, followed by a complete rewrite and a 1200 mile move. Needless to say, I was fried!

I was busy during my residency, but I went in with the mindset that I was going to use my time as wisely and productively as possible. I worked hard. I played hard! To me, this residency was a step towards my ultimate goal, a time sensitive opportunity, very much like graduate school minus the grades. This time, I set the due dates; I gave the grades. I applied to everything: every fellowship, every juried exhibition, and every grant because I wanted the exposure, and the money to make things happen! I failed, got rejected, over committed and underperformed, but out of that, I have built one hell of a resource pool that I constantly refer back to.

One of my proudest accomplishments during the residency was learning how to write a successful exhibition proposal and packet. This has lead to having my work featured in over two-dozen regional, nation, and international exhibitions and being a Sondheim Artscape Prize Finalist. Spending forty hours a week at work and forty hours a week in the studio has been challenging, but it has led to some great things.

DB: When did your interest in ceramics begin? How do you deal with the “craft” issues, the lack of respect, dealing with the medium?

KB: I became really interested in ceramics during my junior year of undergrad. I was in a Ceramics II class and during the classes’ first assignment my professor, Ron Kovatch, pointed to some molds on a shelf and said “get to work!” I place full blame on Ron for putting this “Alice” down the “Rabbit Hole.” During that semester, he introduced me to slip casting, which further grabbed my attention.

I have been questioned by my professors about using ceramics since day one. Some artists retract from the material like it is diseased. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been asked: “Don’t you know that clay is a ‘craft’ material?” I always got a kick out of those discussions during my critiques because it went from a simple question to an all out debate between my professors, who were trying to clarify their stance on “Art vs Craft.” Personally, I think that horse died a long time ago, and if that’s your only criticism of my work, then so be it.

I like the challenge that using ceramic material poses to me. It can be your best friend, it can be your worst enemy, but I can’t help but be fascinated with both a material and a process that has been around for millennia. I respect the past, the tradition of “ceramics,” but I cannot let that dictate the conversation I’m having when making my work. It is important to understand the history of your materials and processes, but if that’s all you focus on, the work becomes a “craft” and not an original idea.

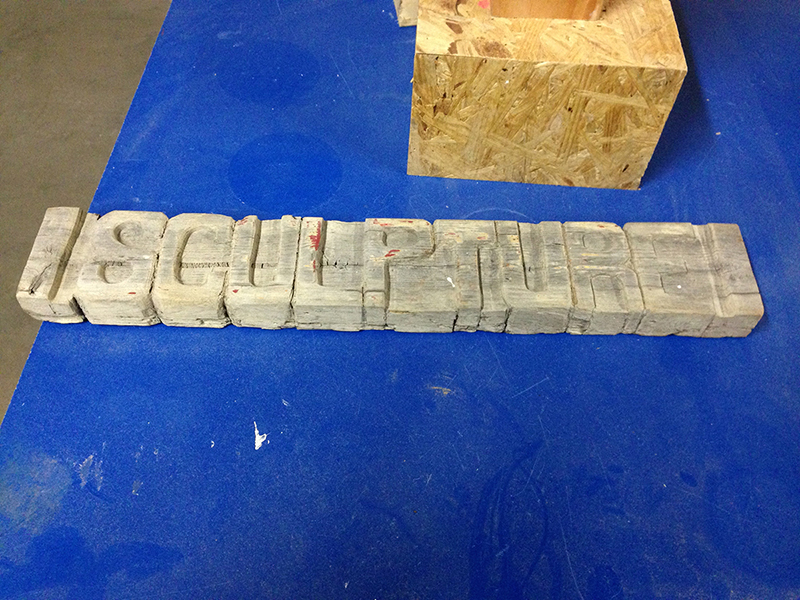

DB: Why do you use porcelain?

KB: The very simple answer is that I use porcelain because I know its limitations. I’ve exhaustively tested what I can and cannot do with the material. I love how strong it is, and having used all types of castibles, I know that nothing beats the strength. Plaster is too soft, resins are way too expensive, and rubbers or urethanes are too unstable. Porcelain pieces will be around until the next great civilization! Also, you can’t beat the endless diversity of surface options. If I want a coarse texture, I use a rough surface and imprint it into the wet cast surface. If I want a smooth metallic surface, I bust out the drywall sand paper, sponge and a bucket of water and get to polishing.

I have been asked this question a lot, defended it more than I care to admit, but I will continue until I am blue in the face. I understand this answer doesn’t always satisfy everyone, but in turn, why does anyone use their materials? At the root of it, I believe it is because they like what comes from using them. No one ever used a material because it made their aesthetic look worse, even when someone is making art with feces.

DB: Coming from the land of excesses, as you describe it, of Southern Louisiana, and being interested in the outdoors, how does this influence your work?

KB: I had the pleasure of going to grad school in South Louisiana, and I couldn’t help but indulge in all that it had to offer. Mardi Gras was a given, the food was to die for, and the lifestyle really agreed with me. I have to say that my favorite though was those legendary LSU football game tailgates, and to top it off, student section season tickets were only $92. There truly is nothing like Saturday night in Death Valley! I digress, but there is a certain type of swagger and decoration that is engrained in the Southern lifestyle. I like that. It really interests me, and I couldn’t help but get caught up in it. It is loud, boisterous and unafraid, but yet still amazingly refined. This complexity was something that I wasn’t immediately comfortable with, but I eventually learned to embrace my southern soul.

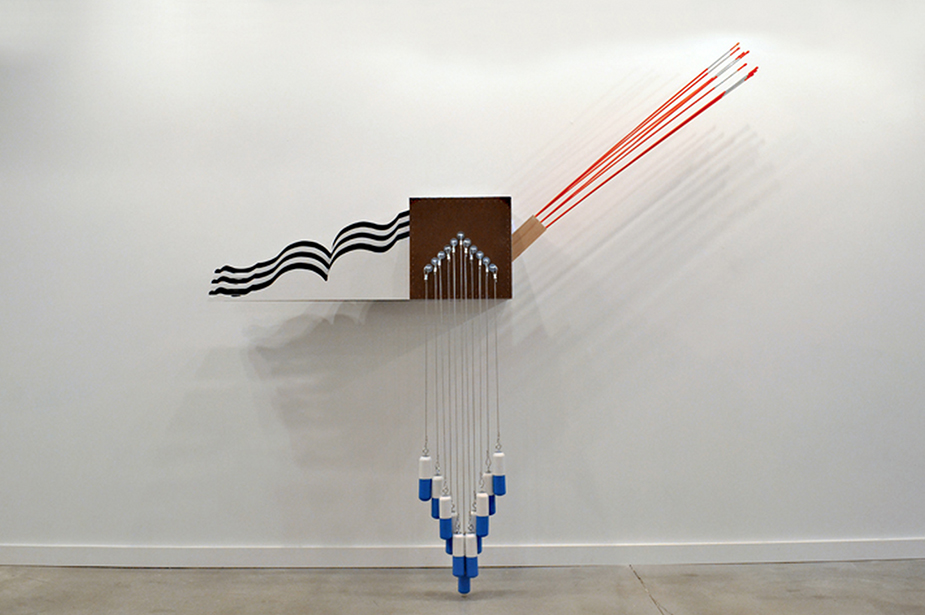

When I needed some quiet time, a notion that came to mind more often than I care to admit, I would ride my bike over to the levee. It was best at night because there were no distractions. I would watch as huge big oil tankers would come up the Mississippi river from the gulf to off load at the Exxon plant in North Baton Rouge. These slow lumbering giants would navigate precisely up the twisting river each and every time in complete darkness. Sometimes I got to see them do the “Texas Chicken,” an avoidance maneuver my merchant marine neighbor told me about. My best explanation is when two large ships occupy a narrow channel of water; they actually steer into one another. They do this not as a challenge, but instead so they can stay within the designated channel. Driving toward one another displaces each boat safely within the channel as opposed to avoiding one another and being displaced onto a sandbar or on the shore. This is what initially inspired me to investigate further into the so call “rules of the road” for navigable channels or bodies of water.

DB: You have a very specific aesthetic and working methodology. What kind of experimentation can come from working like this and keeping within your want to make smart, well-crafted objects?

KB: My clean and very polished aesthetic comes from my love of finishes: finishes like those from the hot rod scene of southern California, and also home décor, minimalism, nature, graphic signs, billboards, designs or advertising. I experiment with surfaces because they contribute to unexpected and interesting compositions. I often collect objects for brainstorming, and transform them by arranging, stacking and piling. I call these my three-dimensional drawings; I then document them either with my phone or in my sketchbook. Even though my final sculptures are aesthetically clean and tight, they are conceived though fluid experimentation. I believe that working intuitively leaves the door open for innovation.

DB: With you being in Baltimore for a little over three years now, how is it been navigating the scene here?

KB: Constantly make work, good or bad. Introduce yourself to everyone you meet; shake hands, kiss babies and do your best to get noticed (in a good way). Apply to everything, and if you get rejected, don’t place the blame on the juror. Take ownership and apply again. KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE; research the panels, read the prospectus or guidelines carefully. Don’t try and tell people they should see a donkey when actually they see giraffe. Another rule I live by is being honest: honest with the work, honest with people, honest with your schedule, and honest about living up to your own standards.

The final bit of advice I can offer is to always be open to critique. Critique your own work of course, but also focus on your writing, your speech, and your presence. I am not the strongest writer, which is why I have two to three people review any statements, proposals, or interviews before they get submitted, including this one! Just because I understand what it is I am trying to say, doesn’t mean that anyone else will. Ask for help! Have you ever emailed the gallery, juror or panel about why you didn’t get accepted? Try it; you’ll learn stuff they don’t teach you in art school!

DB: Being a formalist, concerned with the technical, how do you navigate and deal with an art world that seems to be consumed with derivative masturbation?

KB: I think it’s really easy to fall into the trap of doing what’s hot. I did a couple of times, but you won’t ever see any of that stuff. Well, I guess you could if you want to go to the dump in the places I’ve lived. Grab a shovel and get to digging!

In order to avoid this pitfall, I always ask myself: What is that the message I am trying to convey to my audience? DO I REALLY WANT TO TALK ABOUT THAT? I’m not trying to be “too cool for school.” That’s why I went to school in the first place. I take my career and myself very seriously, and I like art and artists who do the same. I have fun, trust me. But there is no need to be a smart ass or try and pull a fast one on people. I want to be taken seriously, and I can only do that when I’m honest.

DB: You were a finalist for last years Sondheim prize. Can you talk about that experience?

KB: Sondheim was a whirlwind of an experience. Once the semi-finalists are announced, you have around 2 weeks to put together a 30-image portfolio, bio, and a statement of how you would use the $25k prize. The finalists are announced about six weeks later, and from there you have only 8 weeks to design, redesign, build and edit a large exhibition. This entails meeting with the host institution staff, ordering materials, writing statements, submitting images and information for press, and emailing invitations. Finally, on the day of the award announcement, each finalist has a 30-minute interview with the jurors in the gallery space amongst their work. To say I was nervous was an understatement because I knew that a $25k prize was riding on just 30 minutes.

Spring and summer of 2014 was a crazy time in my life. Needless to say, if I wasn’t at work, I was at my studio. I remember being up for about 20 hours a day for 4 straight months because while I was applying for Sondheim, I was also building my solo show for Arlington Art Center’s Spring Solos. The madness only continued when I was selected as a finalist for Sondheim. So when it was all said and done, I drank a beer, made a killer dinner, smoked a cigar, and slept. But I wouldn’t have it any other way!

DB: What do you have coming up?

KB: It terms of exhibiting, I was just selected as a Sondheim Semifinalist this year, so I am currently preparing new work for one of the Artscape exhibitions this summer. I also just found out that I was awarded a Maryland State Arts Council Individual Artist Grant and confirmed my solo exhibition dates for the Rice Gallery at McDaniel College this coming August.

Dwayne Butcher is an artist, writer, curator and chicken wing connoisseur living in Baltimore, MD. Butcher moved here from Memphis in the summer of 2013. In that time he has continued to have international exhibitions, published articles in local, regional and national publications, and curated an exhibition of Baltimore-area artists titled “Bawlmer” at Crosstown Arts in Memphis, TN. To see his work and curatorial projects, visit his website and follow him on twitter @dwaynebutcher.