Way back when, Vito Acconci was something of a bad boy. He bit himself and produced ink prints of the deep wounds. He scorched his own body hair in a nominal effort to obliterate his masculinity. He sat across a table from a video camera and spun a rambling, awkward erotic narrative. He followed random New Yorkers until they entered a taxi, or a hotel room, or an apartment. And in an infamous 1972 piece called Seedbed, he lay and writhed under an artificial ramp in Sonnabend gallery, masturbating and vocally fantasizing about the viewers who strode above him for eight hours a day in a grim routine that spanned two entire weeks.

But time matters; it mellows and distorts. And the Vito Acconci who offered a sweeping overview of his career to a crowd of about a hundred at MICA on April 28 seemed a markedly different man. Now 75, he is noticeably stooped, and speaks in a husky tone that barely surpasses a whisper and is punctuated by a habitual stutter.

As the head of Acconci Studio, he remains productive – but his work has evolved, too, as the virile, combative aspect of his earlier years has given way to an architectural practice that is often sociable in intention, and occasionally even gently nurturing. Consequently, one of the most striking aspects of his talk was the way in which the past was inflected by the present. As Acconci offered concise summaries of dozens of his works, canonical pieces appeared in a new light and the commonly narrated arc of his career was subtly revised.

That’s not to say that his lecture was emphatically revisionist. For the most part, in fact, Acconci eschewed open interpretation, preferring brief, matter-of-fact descriptions to analysis or reflection. As he showed some of his typewritten poems from the 1960s, for instance, he explained that “I started writing because at one point I thought I was a writer. But then I started to do stuff in real space.” But of course even neutral accounts can constitute a sort of interpretation. In turning to Seedbed, for instance, he offered a crisp summary of his experience: “I’m underneath the ramp for a number of days, and I’m trying to constantly masturbate, and in order to do so, I use footsteps.” An inflammatory and baldly unnerving piece was thus distilled into a tidy declarative sentence; described by Acconci, the piece felt something like a water-worn pebble, its edges smoothed.

Through his selection of works, too, Acconci seemed to be proposing a slightly softer vision of his own career. For the most part, his presentation was chronological and comprehensive: Acconci is a speaker who prefers to err on the side of inclusiveness. Given that, it was telling to see him skip over his well-known video works from the 1970s: the works, that is, that prompted Rosalind Krauss to suggest (in a widely read 1976 essay) that narcissism was a quality endemic to video art. Similarly, Acconci omitted mention of a 1983 piece called Way Station I (Study Chamber) that was installed on the campus of Middlebury College – and that sparked wide resentment before it was eventually firebombed by vandals. Speaking as portions of Baltimore still smoldered in the wake of the previous night’s riots, Acconci steered away from an overt engagement with larger contexts and controversies; this was a retrospective free of any explicitly polemical bent.

Still, as he led his listeners through four decades of work, certain themes did emerge. Consistently, for instance, Acconci has returned to the relationship between exteriors and interiors, and public and private space – often frustrating or blurring any easy distinction between such opposites. In a 1976 installation called Where We Are Now (Who Are We Anyway?), a 60-foot plank outfitted with stools resembled a meeting table, but ran straight through the gallery window, projecting into open space well above the city street below. By the 1980s, this interest in dissolving traditional spatial distinctions had grown more ambitious, and Acconci began to develop an active architectural practice. In his earliest experiments, he repeatedly used pivoting elements: portions of walls, for instance, that could be rotated until they served as tables. Positive forms thus gave way to voids, and blunt barriers became something useful.

And usefulness and interactivity, to be sure, have long interested Acconci. “I wanted,” he said at MICA, “people to do something with the pieces.” The formal experimentalism of his early poetry and the aggressive aspect of his performances thus yielded, it seems, to a more social and utilitarian impetus. Benches, for instance, recur in his 1980s designs. So do tables, and the ominous, voyeuristic quality of some of his early works was replaced by an emphasis upon communion. In the process, too, Acconci often explored the theme of shelter. In 1980’s Instant House, for example, viewers were invited to sit upon a swing that was connected, by a system of pulleys, to four thin wooden walls that lay on the gallery floor: the weight of any viewer who used the swing lifted the walls so that they formed a rudimentary surround: a sudden abode.

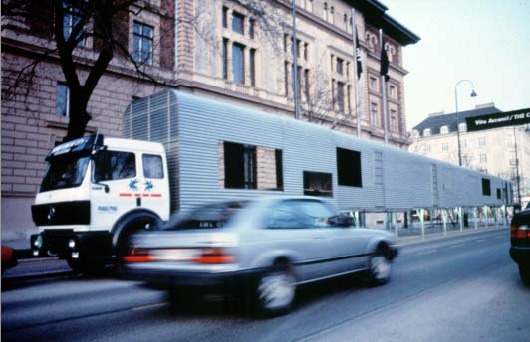

Acconci’s work, then, gradually became more literally supportive – but his artistic career has long been informed by an interest in involving the viewer. (As Robert Smith observed, in a 1988 review, “the core of Mr. Acconci’s vision has remained consistent: it is the desire to generate an encounter in which the viewer becomes a witness, voyeur or participant, whose presence is integral to the work.”) That vision, moreover, is frequently leavened with a wry humor. A 1991 piece entitled Mobile Linear City, for instance, was a seemingly conventional tractor trailer: when parked, however, six telescoping rooms made of corrugated steel could be pulled out, creating a working, functional house. The result is jarringly clever, or humorously simple: indeed, the essential conceit of the piece was embodied in its functional toilet, which was built out of a section of wall that could be pulled down. “You can use the toilet,” Acconci noted with a sly smile, “but your ass is exposed to the outside world.”

In this lecture, however, that wry humor seemed interestingly offset by a hint of wistfulness, or a sense of loss. To be sure, the coincidence of humor and melancholy is a notable aspect of some of his work: take, for example, 1992’s Personal Island, in which two rowboats are half buried, at the edge of a body of water. They seem useless, until we realize that one is in fact surrounded by a floating, detachable island – and that it can thus sail away from land, in a motion that is at once liberating and distancing. The piece evokes, to me, one of the fundamental moments in the history of art history: Winckelmann, all too aware of his ineradicable distance from ancient Greece, comparing himself to a maiden on a shore, watching her beloved sail towards the horizon. Perhaps it’s an unfair comparison, but Acconci, too, seemed pensively regretful, and the result was affecting, as it suggested a new way in which much of his work might be read.

Here’s what I mean. At least half a dozen times, Acconci remarked – sometimes with a slight shake of the head, or an openly nostalgic tone – on the fact that many of his architectural designs have never been realized.

“This is one of those projects,” he said of a proposed staircase in São Paulo, “I thought could have been built – but I’m often wrong.” And again, a few minutes later, on another structure: “If I could have one of our unbuilt buildings built, I think it would be this one.” And, slightly later, in speaking about an unbuilt playground: “The thing about competitions is that mostly nobody wins.” Such comments created a tinge of pathos, and a modest acknowledgement of the limits of what can be accomplished in the face of cold reality.

That tone was only reinforced, in turn, by Acconci’s physical frailty. Emphasizing an artist’s age may seem unfair, or impolite – but, as Philip Lindsay Sohm showed in his 2007 book The Artist Grows Old, there is in fact a dense and meaningful history of such references (think of Vasari, chastising an aged Titian for continuing to paint and thus degrading his own legacy, or of Michelangelo, increasingly reliant on touch as his eyesight faltered).

During his talk, Acconci struggled to read, on the computer screen before him, some of the poetry that he had composed a half century earlier. And yet, such moments were more stirring than embarrassing, as they granted a new life to some of the projected works. One poem, for instance, that was centered around reading – “Do not read this. ‘Do not read this,’ I say” – suddenly seemed as much a comment on the inevitable loss of authorial control as it did a study in willful, ironic exertions of power. And when Acconci strained to make out lines in a second example (“I am here. You are here now.”), the lecture almost felt like a vanitas painting. “I once was,” reads the Latin text in Masaccio’s most famous altarpiece, “what now you are, and what I am, you shall yet be.” You are here now, Acconci answers – but only, we understand, for now.

Viewed thus, Acconci’s entire body of work appeared in a new light. Seedbed, again, is usually read in terms of voyeurism, a grueling physicality, and an erosion of any genteel division between private and public. But on Tuesday, it seemed as well to be a meditation on absence and distance: his autoerotic fantasies, after all, were based on nothing but footfalls and imaginings. Similarly, Following Piece now seemed as elegiac as it did aggressive, for Acconci’s quarry, we now realized, always disappeared in the end. The elderly artist, then, may regret pieces that were never realized. But perhaps that sense of regret, in fact, is nothing new. Perhaps, indeed, it’s always been a meaningful part of his practice.

And in that sense, perhaps we should see his work not in terms of narcissism but rather in terms of something more exterior, more social, and more relational. In a chapter dedicated to the theme of the aging Narcissus, Sohm quotes Baldassare Castiglione, the Renaissance courtier. Arguing that the judgment of the aged is often clouded and erratic, Castiglione contended that the very old resemble “people who, as they sail out of the port, keep their eyes fixed upon the shore and think that their ship is standing still and that the shore is receding, although it is the other way around…” But no: not here, at least. For in a piece such as Private Island, Acconci allows us rather to sail or to sit on shore – to choose from either of the two rowboats, and to realize in the process that staying and leaving behind are inextricable related.

I am here. I follow you. The inside becomes the outside. Your ass is exposed. And what was once easy to read becomes more challenging.

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.