by Nicole Ringel

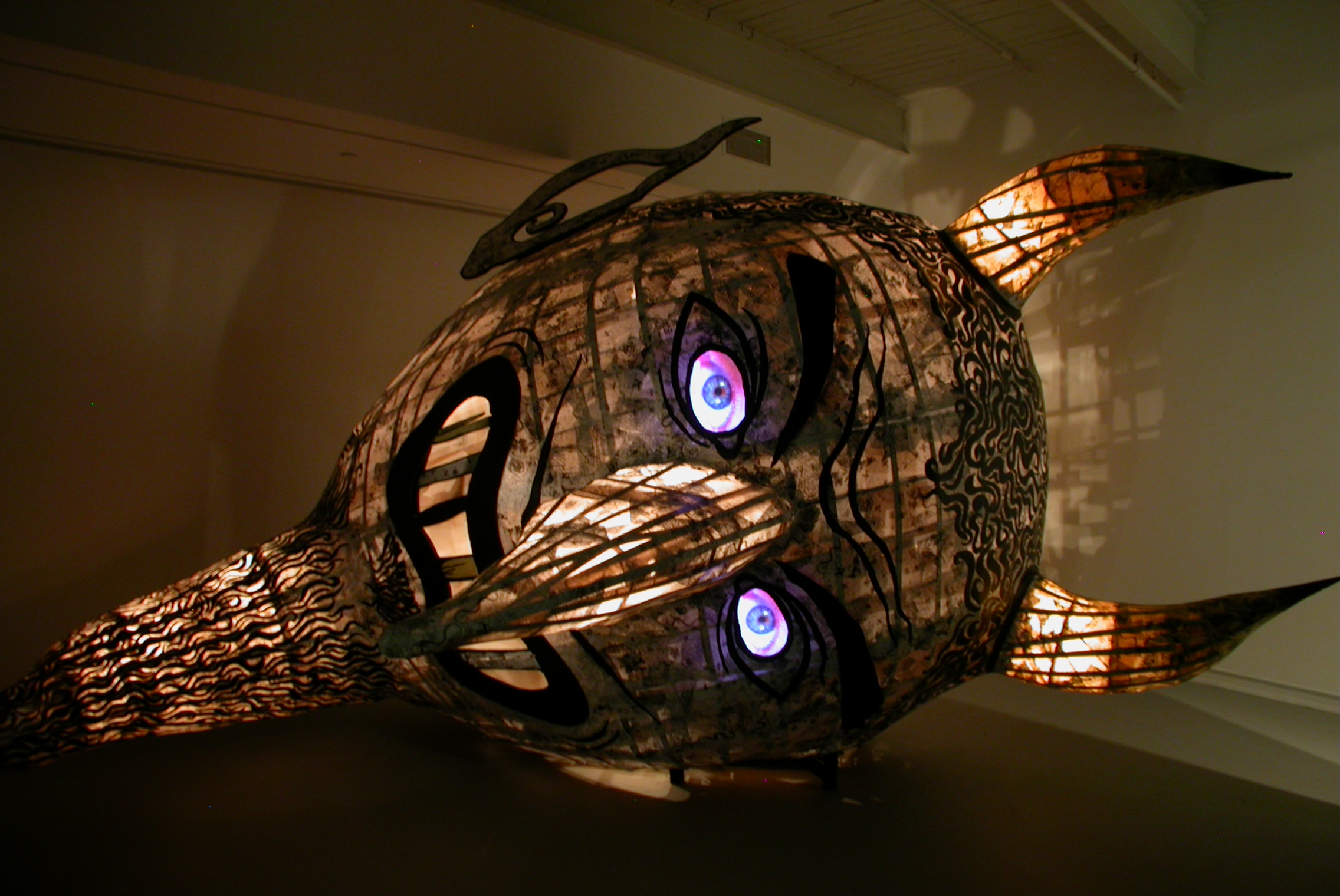

Laure Drogoul has been an interdisciplinary artist and self-proclaimed “cobbler of situations” in Baltimore for nearly thirty years. Her work varies from sensory experiments to large-scale installations, but each emphasizes the importance of viewer participation and tactile experience. Drogoul brings attention to gaps, cracks, and crevices – both literal spaces and in her viewers’ thinking. Through a variety of partnerships, collaborations, and experiments, she uses irony and participation in an attempt to provoke new lines of questioning.

We sat down at Red Emma’s in Station North to talk about her work. This transcript is part of that conversation.

Nicole Ringel: For readers unfamiliar with your work, could you explain your practice in general and your more recent projects?

Laure Drogoul: Well I consider myself a sculptor and a performance artist. I always refer to myself as a “cobbler of situations” because I orchestrate events in a sense. I’ll create something that’s framed in such a way that it will invite a participant to engage to transform their experience of it. I think that’s what my performance practice is mostly based on: considering my immediate environment, the city is my canvas in a sense. I frame it, and then create works that will engage my audience, or someone, or a tour, or a participant. It’s always hard because my audiences tend to be more participants.

NR: Nearly all of your works rely directly on active viewer participation. Could you explain your interest/desire for that and how it contributes to your work?

LD: I think one of the reasons I’m interested in that is that I find it a really dynamic and unknown methodology. In other words, it’s not like you’re saying, “I’m going to create this and then it’s going to be made,” it’s very collaborative. In framing it that way, anything can happen, and that anything can happen is very interesting to me, and it also allows for other thoughts to be engaged and hopefully to elevate the conversation.

But I don’t really have a requirement of reaching any conclusions per say. I just like the unknown dynamic; it keeps me interested. It’s not unlike drawing or painting. If you’re a watercolorist you might wet your entire paper and throw your paint on there and see how it responds. I’m just a people person, so I just gauge people in that way. Most artists manipulate paint or wood or something else; I do that as well because I’m a 3-dimensionalist, but those objects are usually made with a theatrical conceit or as a performative piece.

NR: You have mentioned your use of vacant lots and under utilized spaces in your work. Your installation with the repurposed water jugs- “Eastern Lights” reminded me of this a lot. Could you talk about your motivation for using these unexpected places?

LD: I like the idea of infiltrating the minds of the viewer in a space they might not suspect it. It might give them cause to think. In terms of the water jugs, they’re all marathon water bottles so obviously people run around and they generate all these plastic jugs. Of course that’s necessary, but afterwards I thought how funny it is to be running and see the jugs you use for the water. Here they are in another iteration in another space. Also I’m really interested in the everyday object and the vernacular, and that goes along with the site being vernacular too. It’s a pedestrian space, it’s not a sanctioned kind of art space.

NR: Were the jugs hanging during the marathon for the runners to see?

LD: They were last year. You know, I’m not actually sure that the runners run on Eastern Avenue. That project really came about because the southeast CDC and the Creative Alliance wanted to have something in that neighborhood so I suggested these swags. And at the same time I had been directing the Lantern Parade for three years. When I directed the Lantern Parade, we made the lanterns entirely out of repurposed 1 liter or 2 liter jugs. The idea was to create an environmental initiative and at the same time challenge all the kids in some workshops to see what they could make. Again, the bottle worked really well because it was a very common, and unfortunately ubiquitous object and it’s lightweight and transparent. So it could function as a lantern very easily.

NR: Are the environmental themes in your work a new theme you have brought in, or has that been important to you throughout your life as an artist?

LD: I’ve always loved nature. I also work with clay to a certain extent, and I love sort of the tactile aspects of nature and the environment. I have real commitment to body-to-body, face-to-face, eye-to-eye conversation. In about 2004 I did my first garden piece, which was in a sculpture at Evergreen House. It was just a large mask of a devil, and inside of it was a garden, and it was located in a garden. I think it was then that I really started to focus on things that grow, and nature began to manifest in my work.

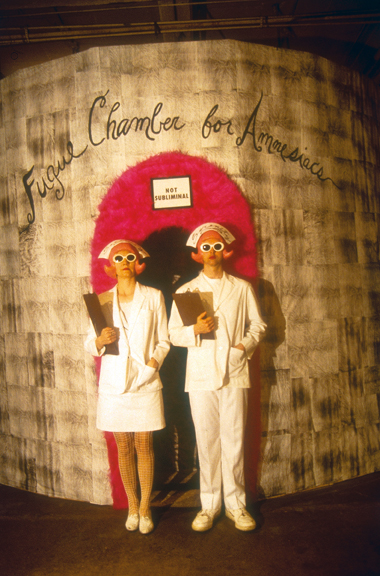

NR: You are also an organizer of the Transmodern Festival, an event for “radical, live art both on and off the stage.” Can you talk about the founding of that event, and the motivation behind it?

LD: The Transmodern Festival was started primarily by Catherine Pancake, Bonnie Jones, and Jackie Milad. Bonnie and Jackie got a space in a factory, and they wanted to have a performance festival there. So she asked me to perform in it and be part of it. I got engaged there in the first year primarily as an artist, and then later I curated some different shows.

My first deep involvement came with curating Pedestrian Service Exquisite, which is an event in the festival that was primarily dedicated to the spaces in between the cracks in an urban environment. I co-organized that with Rebecca Nagle and James Maher. It was something I was very very interested in and had been interested in for a number of years, literally inviting people out into the street to do tours, to do tours myself. I had already started as the hostess of smell doing smell-based tours in different places. Actually, I could probably say that my smell project, The Olfactory Factory, is deeply involved with nature as well. And I can really say what brought me there was everyone’s interest. With that project I would ask people in different places about their olfactory interests. I became of aware of industrial smell versus natural smells, scent environment versus not. That also influenced my awareness of natural world and possibly intervening in that world.

So, going back to Transmodern… When my friend Catherine Pancake officially left Baltimore, I became much more involved in it. I had been on the board and performing in it, but I took on a more central role. I think a big part of Transmodern is that it is trans. There will be a body of people who are involved in it, and then another body of people will become involved. So I imagine at some point becomimg not necessarily less involved, but maybe less organizationally.

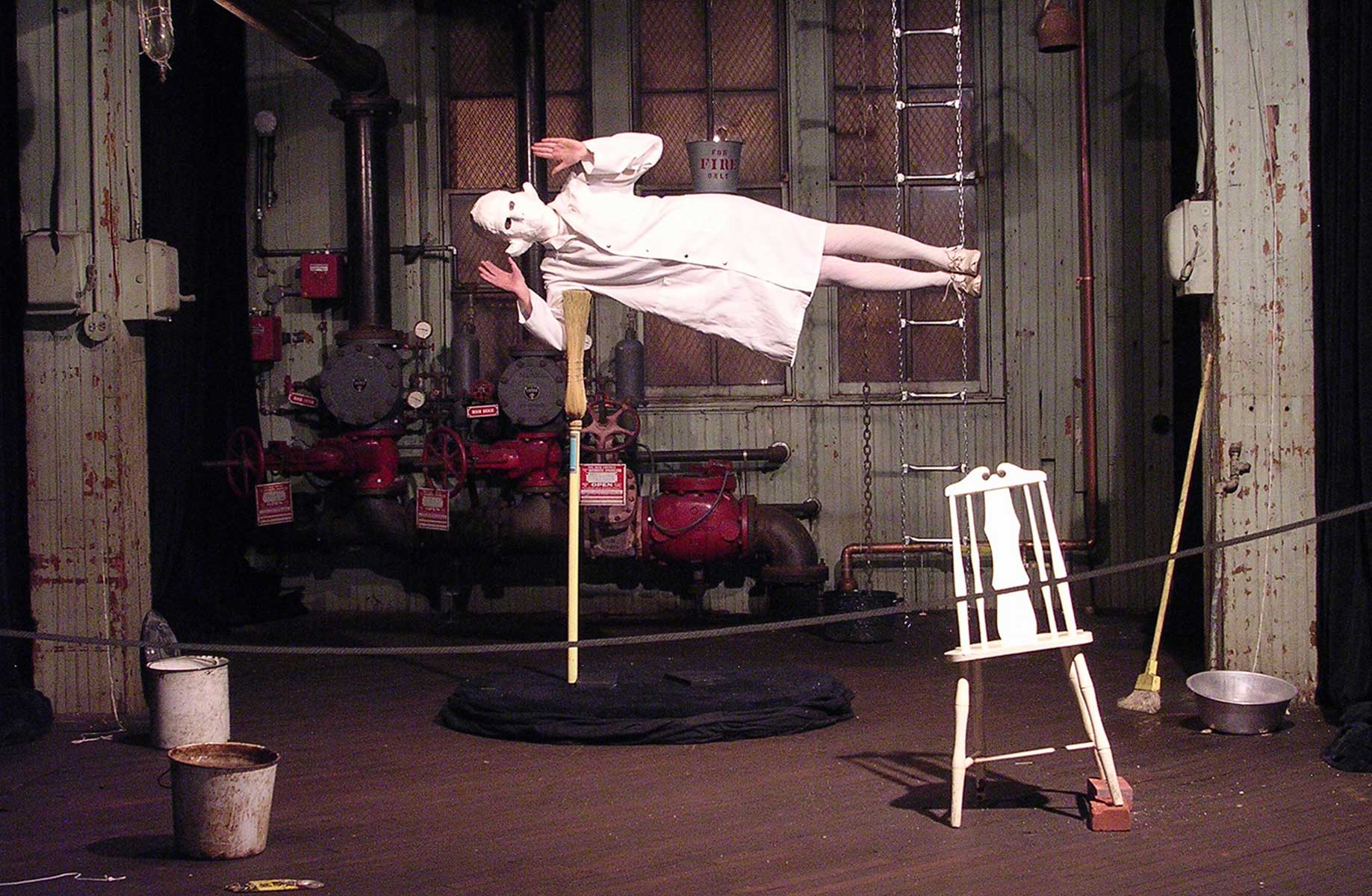

NR: One of my favorite performances of yours is “Art Guard” in which you suggested that the art guard be considered a part of the museum. Could you explain what led up to this work and your thoughts behind it?

LD: I think that you go into a museum space, and are obviously informed by everything in the space, but we’re kind of asked to put blinders on. We don’t really see the guards, the cracks in the wall, or the ladder over there. We see what we actually came to look at, which is essential. But really the overall experience is just like the cracks in the wall. You really are privy to experiencing the entire space. But I feel like the guards are always over there, in plain view. And I really love observing the people who are invisible in plain view.

So when I was invited to be in this event [The BMA’s 100th Anniversary Party], I thought I would like to become one of those people— a guard. And then of course that brought in the idea that we’re all art, and what the art of the future be. That was a part of LabBodies, they curated a whole group of things that I was a part of. I was also interested in the movements connected to being a guard. The idea of becoming art, and then protecting themselves as art is serious but again, I also use humor a lot. I would love to do that performance again, but truth be told it was so busy that night and so crazy I think by the time you were trying to move to do your thing it became difficult.

I was completely masked and I could not speak at all. It was completely what you ask of a guard in a way. You don’t really expect the guard to be talking, you expect a guard to be all eyes watching. I couldn’t speak to anyone, and I actually had a tape that I gave to participants that put forth the idea of what I was going to do. The tape was a lesson in self-protection— because we’re art, they’re art, everything is art.

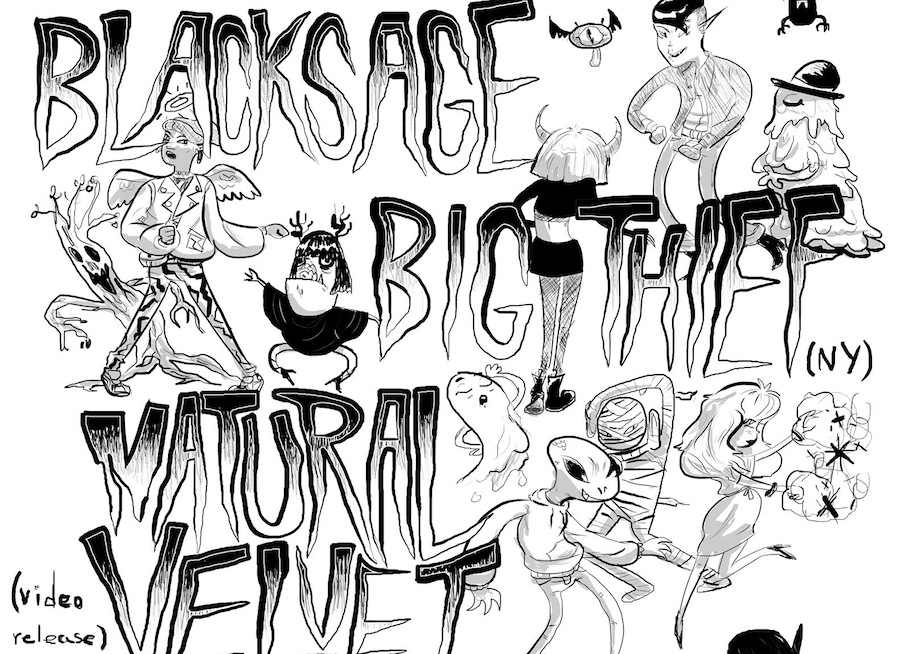

NR: Also in the realm of performance art— you’re the director of the 14 Karat Caberet. Can you talk about the performances you’ve put on with them, and what’s going on now?

LD: The Cabaret is a really long time hybridized relationship that I have with Maryland Art Place. They have a building on Saratoga Street and years ago I rented a space and did a cabaret and fashion event there. I was cleaning up after the event and found a room down in the basement and I thought, “Ooh, this could be a great laboratory for performance art.” So I rented that space for a few months, and later on I had a friend named John Henley who worked in the gallery there. He was like, “Well you know, this is great. We should do this all the time.” This was in 1989, so there were very few performance spaces in Baltimore. It was just an idea that was beginning to take hold. In terms of having a space where anybody could come down and workshop and practice performance art, there really wasn’t anything.

I organize shows and I invite people to do shows there. I maybe do it once or maybe twice a month, or four times a month, all based on availability and what’s going on and all that stuff. I named it the 14 Karat Cabaret because there were a lot of gold shops. It was at the end of the 80s— the economy was bad, and gold had a lot of value so there were a ton of gold shops on Saratoga Street and Howard Street. So we named it the 14 Karat Cabaret to fall into that.

NR: I’m really interested to hear how you’ve seen Baltimore grow and develop over the years, since you’ve been here so long. What’s your perspective on the way Baltimore has changed and the direction it’s headed in?

LD: Baltimore has changed quite a bit. There were definitely things going on here; there was a group of artists that were working, there was the Second Story Books, the Ad Hoc Fiasco, which was a big event. When I got here in the early 80s I was engaged with a lot of different artists doing things, but now there is quite a lot more. I think what happened is that it’s just so expensive to move into larger cultural centers that artists are just deciding to stay in smaller cities and transform the cities that they can easily live in. And as a result, there are tons of changes.

For instance this whole North Avenue is greatly transformed and I think a lot of it is a mix of grassroots, business, and academia. It’s really hard to know how it all happened, but clearly now there are a lot more events going on. And there has been renaissance of different parts of town that have come and been swept away. When I think of Southwest Baltimore, they have a huge festival there that used to be just gigantic, and then it sort of went fallow for a while, and that neighborhood went away. Now it’s back a little bit and the festival is happening again. I think that there is ebb and flow, and who knows what’s going to happen here. There is major investment specifically in North Avenue because of Johns Hopkins and MICA and some of the other businesses around here.

NR: Have you been excited about most of the changes you’ve seen? It always seems like a double-edged sword when artists move into places that aren’t used to having them around. I look around and think the growth of the artist community is really great, but it’s important to be aware of a sort of balance.

LD: It is a balance. And it’s really tricky. So I live on Howard Street in Mount Vernon. There has been some change, but not much. It’s beginning to happen now. There are still lots of empty buildings and decay, and crime, sometimes hideous crime. It hasn’t changed that much on my block I would say, with the exception of the large M on Madison, which was supposed to be workforce housing.

So with that going in on that block that sort of addresses that issue, you could call that a balance. The other thing is who you’re going to have come in. That would be the issue to be sensitive about. Even on the block Maryland Art Place and the Cabaret is at on Saratoga Street it’s important to think about. It’s a very busy block and it’s very Middle Eastern. I really like that because it has a lot of character. It’s got a sort of different ethnic perspective, which I think is really important no matter what. I would hate to see all that get chased away in the name of renovation.

I do feel that artists need to own and buy if they can to secure their situation. It’s sort of a drag because it’s getting more and more expensive to do that but I think it’s helpful because that way there is some sort of hope that artists won’t get kicked out.

Even in the 80s I remember people renting spaces, fixing it all up and then getting the boot. And that’s not saying that people won’t try to take your building away even if you own it, but it’s a hell of a lot harder. The real estate is somewhat depressed right now so it’s a good idea to invest in it now if you can muscle it, and instead of paying rent pay less and this way if you feel you’re going to be around for a couple of years you’re more secure. That’s a benefit of living in a city as small as this one— you can buy at this point. I don’t know how long that will be, because of the whole gentrification thing.

NR: You’ve also had the opportunity to exhibit your work internationally in both Japan and Russia. Can you talk about how those shows came to be, and the difference in exhibiting your work outside of Baltimore?

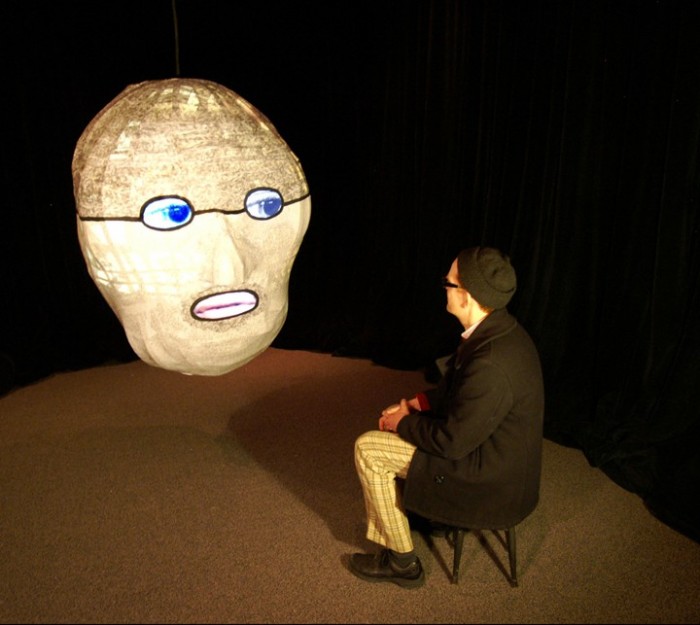

LD: I actually got a fellowship to be in Japan for 6 months. I went there and met different people and partnered with different artists. I met so many different people, and through that, I was in a couple of different shows there. I did a couple of different scent-based installations that I call “Scentoriums.” I did a Scentorium in a gallery there that was very interesting. The way people responded to smell there was completely different than say in Russia or in the States, because they have a very different idea about body and body space.

I’ve been to Russia a couple of times. I went once with my knitting project, which is a sound project. I went there in 2011 for a festival called Cyberfest, which was just an astounding experience. It was a huge warehouse festival in St Petersburg. I went in and sent up my installation, and all of the babushkas came and knitted. I met a ton of different people there, but it was very hard because there was very little English spoken. Very often when I do projects like this it’s very male-dominated. Tech stuff and computer-based art can be very male oriented. That’s changing, and that’s why I chose to do the knitting project, taking the idea of knitting and making it high tech so women can come and they can see everything that’s going on.

The first time I went to Russia I went through a show that was organized by School 33. It was called Baltic Mist, and it brought a few artists from Russia to Baltimore and then they chose three other artists of which I was one to go from Baltimore to Russia. That was for my smell project, again. I set up a Scentorium, where I had a cart set up with a bunch of what people told me were the most interesting smells in Baltimore. I did a mapping of that and then went and collected smell samples, like a can of Natty Boh and frozen crabs, and I offered myself as a smell specimen.

The gallerist spoke no English, but her husband knew a little and could translate a little bit. I had a chair, and someone would sit across from me. We would smell each other and that’s how we would get to know each other. Through the course of the evening people would go “Hi, how are you” and so it promoted a dialogue. That’s something I’ve been interested in forever. All of my pieces are sort of ‘4th Wall’ pieces; they’re all breaking the 4th wall of the theater so you can see behind the artifice.

Smell is space; it’s invisible space. Again, it’s the same thing: how we create our spatial relationships with humans and with objects. There are all sorts of things that are a part of that, and certainly smell is a part of that as well.

And then one person there, I’ll never forget, said something like “I cannot stand the smell of a perfumed human!” Which was totally the opposite of what I had seen in Japan. So he didn’t want anyone to feel like they’re covering something up; he much preferred the honest scent of a human being. I think it’s really funny that I remember that, because he was just one person that I met, but it’s also interesting in terms of their history. Specifically, their political history of covering things up. Of course he couldn’t stand covering up smells, he lives in a world full of covers like that!

NR: Is your work with smell something you’re looking to continue?

LD: Yes, recently I’ve been working on a project called Nosestalgia. It’s a tour of Baltimore collaborating with Graham Coreil-Allen. He came to the first PSE at Transmodern and that was one of his first tours. Three people were going to work with him on a day of chores for his exhibit but because of the uprising of course he cancelled it because he felt that it was untimely.

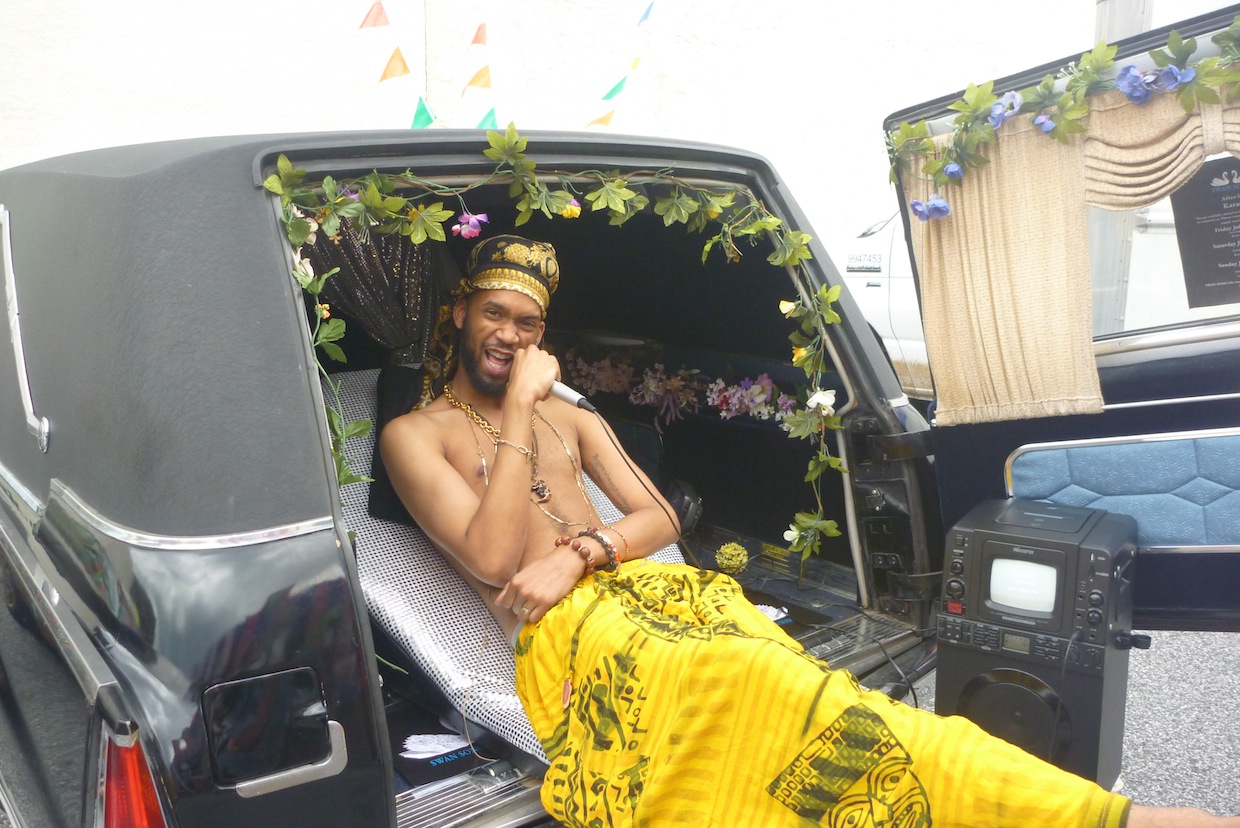

NR: It seems to me that all of your work has an element of playfulness to it— singing in a hearse, listening to the clicking of knitting needles, and admiring the “faux bow” of empty plastic bottles… Is absurdity something you strive for in your work?

LD: I think that absurdity, irony, humor, and all of its woven relationships; even collage and juxtaposition of events create portals that allow for awareness. It brings you to a place where you’re either open to new idea, or it’s been able to seep in whether you’ve rejected it or not. I think humor works that way; it’s profoundly informative.

And this puzzle opens up a gap in your thinking. Things aren’t as pat as you thought; there is a shift in consciousness, and it eases the drudgery of everyday consciousness in a way.

Humor also works free of the narrative conceit, specifically visual humor. We don’t have to have a narrative to draw skin. Humor works in tandem with that stuff, but it’s a lot quicker. Maybe I’m giving it too much emphasis, but I think that’s the way I’m interested in art. I think it’s hard too. You’ve always got to find a balance where the humor or the absurdity doesn’t become the total piece. It’s only part of a puzzle, especially if you’re trying to get the viewer thinking about other things. Imagery and juxtaposition allow a person to think about a myriad of other things and so you’re trick with that is to not in total let the humor take over.

Some of the greater issues are so multilayered and juxtaposed just like that. There is no any “all good” and there is no “all bad.” Humor brings you to the grey and you see multiple sides, laugh at it, and recalibrate positions.

Author Nicole Ringel was raised in Frederick, Maryland and is currently pursuing a BFA in Studio Art and Art History at McDaniel College in Westminster, Maryland. She is an artist and reader, and is especially interested in community and socially engaged art.