Hani Alqam: Of Love and War at XOL Gallery reviewed by Seola Lee

Hani Alqam’s Of Love and War, his first solo exhibition in the United States at XOL Gallery in Baltimore, is an attempt at expanding freedom of expression towards taboo or culturally sensitive subjects through a repeated artistic genre.

The Mt. Vernon gallery’s name, XOL, comes from the ancient Roman slogan in Latin, “Ex Oriente Lux,” which means “Light Comes from the East.” Housed in a renovated former warehouse, surrounded by a garden behind a tall, wooden fence, the gallery has provided a platform and safe haven for young Middle Eastern artists with limited chances for practicing and presenting their art due to sociopolitical influences in their homelands.

Despite a well-established artistic career in Jordan, certain genres of Alqam’s works presented here have never been shown in Amman. After spending a few weeks in Amsterdam, the artist began obsessively painting female nudes, a choice of subject mostly prohibited in Jordan due to strict religious doctrines.

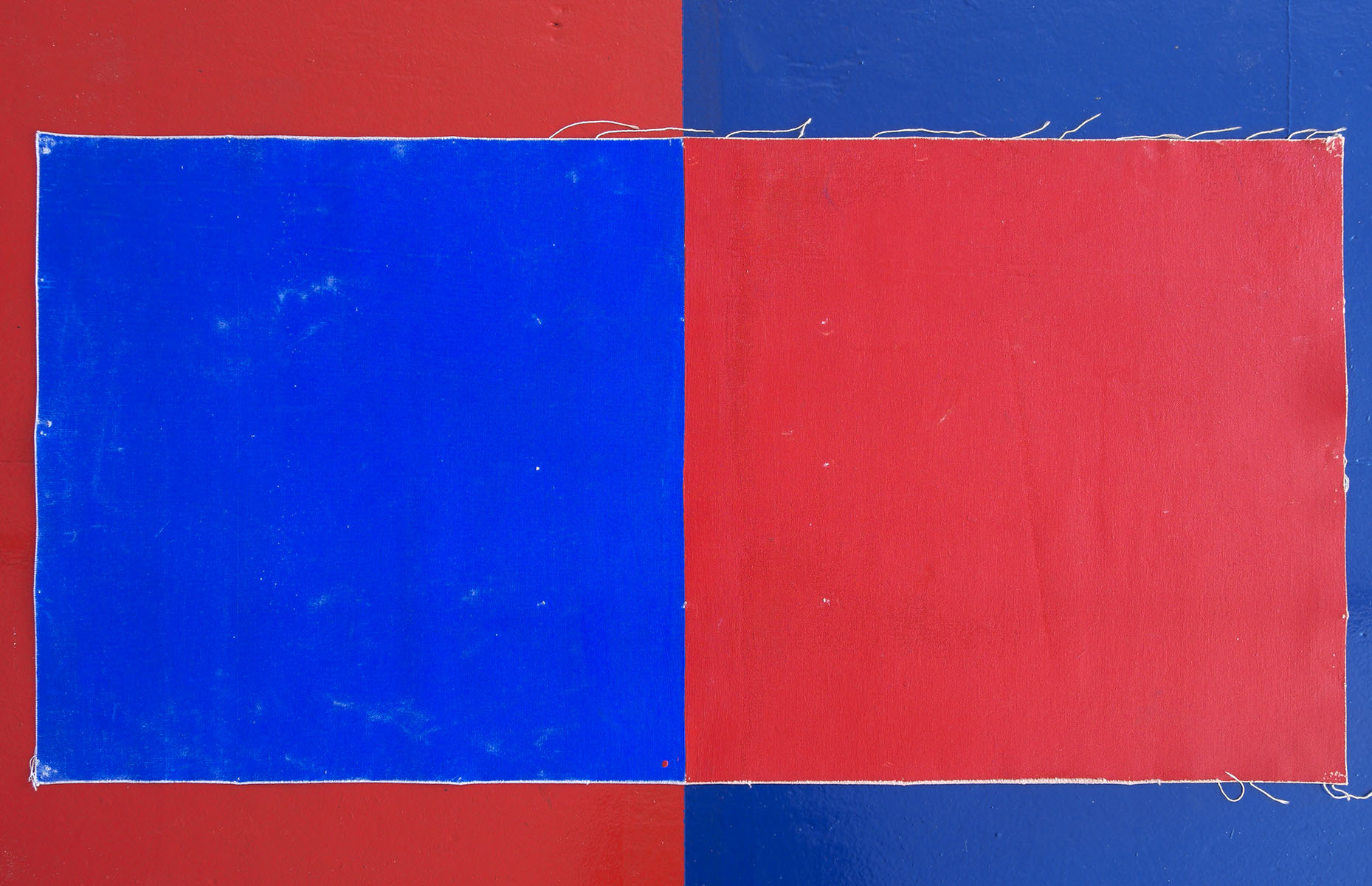

Of Love and War features varying works from 2012 to 2015, painted in his hometown and current base Amman, as well as in Amsterdam, and Baltimore, during his artist-in-residence program at XOL. Despite a shifting environment, Alqam’s visual signature remains consistent—deep, bold colors in violent swirls and texture added by thick brush strokes to convey a highly saturated frustration. Alqam’s technique reveals a rebellious response to socially and culturally built taboos and general political turmoil in his country, which has engaged in a long, unending state of war since its independence in 1946, including the First Arab-Israeli War, Black September, and recent intervention against ISIS.

Alqam features numerous human figures in his paintings, mostly in single portraits or groups. Instead of merely focusing on sensualism, his nudes demonstrate a rawness and bareness—humans in their natural state the way they are born, unconfined by manmade regulations. The depiction of women deliberately exposing themselves in different poses evokes a mixed sense of boldness and discomforting vulnerability at the same time. The fast and loose way he uses his brush is accentuated when he paints extremities—in “Anemone,” “Seduction,” and many others, he intentionally leaves out specific details in hands, arms, and legs, leaving them as vague, amorphous smudges, and insinuating the powerlessness of the people.

Although you could argue that the artist’s recent attraction to female nudes may be “l’art pour l’art,” or art for art’s sake, to simply present his fascination with the human form, Alqam’s titles suggest otherwise. Considering his cultural background, the act of painting a nude is a personal revolt against sociopolitical oppression, not only limited to taboos against nudity, but to freedom of expression in general.

The acrylic painting titled “ISIS” delivers this political message straightforward. In it, a naked woman leans against a blue couch, with her face veiled in a black niqab and her hands listlessly resting right beside her bare torso. The contrast between her veiled face and exposed body mocks the oppressive nature of the clothing, emphasizing the muted voices of many Muslim women. The niqab in the painting also blocks any kind of eye contact with the subject, one of the most primary, non-verbal tools for self-expression and communication. A similar barrier also appears in “Oriental Night,” in which a faceless and handless woman lifts her arms above her head as if tied up and hung by an invisible force.

Many of Alqam’s portraits do include the subjects’ eyes staring right at viewers—their gaze, inquisitive, seductive, appealing, or all at once, engages them on a personal level, as a dialogue. This repeated concept of eye contact or “gaze,” which requires the presence of both the viewer and the viewed, is especially embodied in two works: “Witness” and “Guilty.”

“Witness,” featuring the most number of human figures in one work, captures what appears to be a frenzied sexual orgy. In the bottom corner, a woman’s face looks out, as if she is longing to be a part of this bacchanalian scene. The woman, an assumed “witness,” faces us instead of the moment behind, making us wonder about the power or role of the eyewitness, whose mouth is also excluded in the painting. The viewer is also implicated as a watcher-bystander, as art censorship and deeply-rooted injustice to human rights are pervasive, even in self-acclaimed liberal, democratic countries like the U.S. where social media, such as Facebook and Instagram, has censored art projects like Erik Ravelo’s “Los Intocables” for controversial nudity. The public “gaze” toward these issues, constantly filtered and biased under numerous subtle influences, can be an individual and political force.

Another piece titled “Guilty” shows the face of a man, possibly a self-portrait of Alqam’s conscience as an artist and a “guilty witness” in his community. His big eyes, welling up with intensity over his green-blue face, ask who is guilty and how, using the direct power of eye contact.

Aside from his politically construed works, “Mutual Understanding” is one of a few pieces that directly relates to the theme of love. Possibly inspired by René Magritte’s “The Lovers,” Alqam paints two facing heads, their noses touching and commingling with each other in a big brush stroke. His portrayal of love surpasses mere fondness or liking—instead, it reflects on more profound, complex attachment or yearning, something he cannot easily disregard despite all the anger, incompatibility, or “mutual misunderstanding,” depicted with turbulent, burning shades of colors.

This kind of deep affection encompasses all of his works in the exhibit, proving that Alqam’s passion and subject have always been his people, his culture, and his society. Among them, “Arab Spring I,” “Arab Spring II,” and “Arab Spring III,” are the only landscape pieces included. All completed during his artist-in-residence in XOL, they show scenarios comparable to Birnam Wood walking toward Dunsinane Hill in Macbeth. Like the moving forest, imminent and overwhelming, he stages grand fields and hills by overlapping paint strokes in varying colors and directions, wildly, as if he is trying to rip off the canvases with his brush, the way wars have torn apart the country. The outcomes are lush and dark at the same time, like the air right before the storm, and signify his outlook on the future of the Middle East.

The generic title, Of Love and War, effectively summarizes the way Alqam’s paintings unpack his personally perplexed state of contrasting and rich emotions. Both “Love” and “War” do appear as main themes in his works, through war-torn landscapes and lovers’ faces, but those two states also reflect his inner conflict in a literal sense. In this exhibit, we witness an artist struggling to reconcile his affection toward his nation as home and rage toward its oppression, injustice, and wars causing numerous sufferings. In other words, he uses his art as the primary measure to resolve his inner war.

Hani Alqam’s Of Love and War was on exhibit at XOL Gallery from July 25 – August 15, 2015.

Author Seola Lee is a Baltimore-based poet whose work has appeared in Baltimore City Paper and The Baltimore Ekphrasis Project. Check out her website here.