René Treviño interviews curator John Chaich about Queer Threads at MICA

Queer Threads is not a niche exhibition brought to MICA for fiber students or to fill a diversity or LGBTQ quota. Rather, this exhibit is loud and proud and full of thoughtful, powerful work that screams about feminism, queerness, sexuality, and virtuostic prowess. The exhibit, curated by John Chaich, brings together 24 artists who explore “notions of aspiration, socialization, and representation within the LGBTQ community by employing thread-based craft materials, techniques, and processes.”

I’ve been waiting for an exhibit like this to come to Baltimore for a long time. I am a huge fan of the work that comes out of the fiber department at MICA and this exhibit will speak strongly to those students with solid examples of tapestry, crochet, quilting, needlepoint, etc., but Queer Threads speaks to all kinds of viewers. The content here is baked in and might feel specific (or niche), but there is such a giant range of materiality, experimentation, process, and color here that anyone who experiences this exhibit will leave amused, invigorated, and inspired.

What follows is a conversation with curator John Chaich whose generosity is evident; he is a champion of these artists and has a clear affection for the subject matter at hand.

Liz Collins, “Accumulated Pride,” 2014, cotton and other yarns loomed during KNITTING NATION performance installations, 2005-2012. Image courtesy of René Treviño.

Liz Collins, “Accumulated Pride,” 2014, cotton and other yarns loomed during KNITTING NATION performance installations, 2005-2012. Image courtesy of René Treviño.

Can you speak to the ways feminism and queerness overlap in this exhibit?

Feminism teaches us to question systems, expectations, and privileges, that deny opportunities for women, devalue the feminine, and restrict freedoms of gender expression or sexual identity.

Queer Threads presents art and craft practices long-associated with women and thereby considered lesser than work by men. The female-, trans-, and male-identified artists in Queer Threads embrace the so-called “women’s work” of fiber art and crafts, and in doing so, honor the artistic talents, ideas, and legacies of women.

In various ways–some conceptual, some political, some nuanced, some strategic–feminism definitely informs the work and practices of featured artists like Harmony Hammond, Jesse Harrod, Liz Collins, LJ Roberts, and Sheila Pepe.

Elsewhere, gender-specific works like Nathan Vincent’s crocheted and knitted men’s locker room benefit from feminist readings.

Works like Ben Cuevas Genitosexual or Buzz Slutzky’s “Body Party” series blur binaries or biologies.

And it’s fascinating to me how Maria Pineres–as a lesbian, Latina artist–employs gay male erotic imagery in her work to explore sexuality’s urgency and power.

Through related public programming, I hope that involvement of queer feminist scholars Julia Bryan-Wilson, Ann Cvetkovich and Jeanne Vaccaro, as well as Baltimore activists like self-proclaimed Marxist-Feminist queer woman of color Tori McReynolds, will bring out healthy, hearty critiques of the exhibition and related discourse.

Neither “craft” nor “feminine” should be dirty words in the canon or in communities, I say.

Larry Krone, “Then and Now (Rainbow Order),” 2008. Yarn, wood, and hanging hardware.

Larry Krone, “Then and Now (Rainbow Order),” 2008. Yarn, wood, and hanging hardware.

What was the process of creating this exhibit, can you speak to how the project evolved and how the work was selected?

The exhibition comes from a very personal place: I grew up in a home where my mother and grandmother crocheted and quilted. As a gay man, I naturally was drawn to queer artists working in these mediums.

On a deeper level, I wonder sometimes if Queer Threads could be the affect of seeing the AIDS quilt in its entirety in DC in the mid 90s–where I saw hand-made works of love and pain and passion remembering the lives of people of color, gay men, and trans warriors, all in one interwoven piece of art and activism. Queer Threads is also influenced my two decade-long friendship with teacher and scholar Lyz Bly, PhD, and our discussions on Third Wave feminism’s “taking back” of craft.

I started researching and developing the concept that became Queer Threads as early as 2011; at that time, I had just curated a traveling exhibition of text or language-based works and wanted to explore more tactile works and surfaces.

When selecting work for Queer Threads or any exhibition, I’m very mindful of exhibition design: how works will interact with each other and what variety of scale and media will engage viewers at both an intimate viewing or quick glance.

I also particularly am interested in what happens to works by artists at various stages of their career or recognition, and/ or artists who are working within and outside of the gallery or academic system, are shown together.

Of course, Queer Threads has never attempted to be or could ever be the penultimate, all-encompassing survey of contemporary lgbtq fiber practices; no one location, production schedule, or budget could ever allow that in one given space and time.

But I do hope that Queer Threads can inspire other exhibitions and programming to highlight the tremendous, and often under-exhibited, talents of many queer artists working in fiber and textile across cultures.

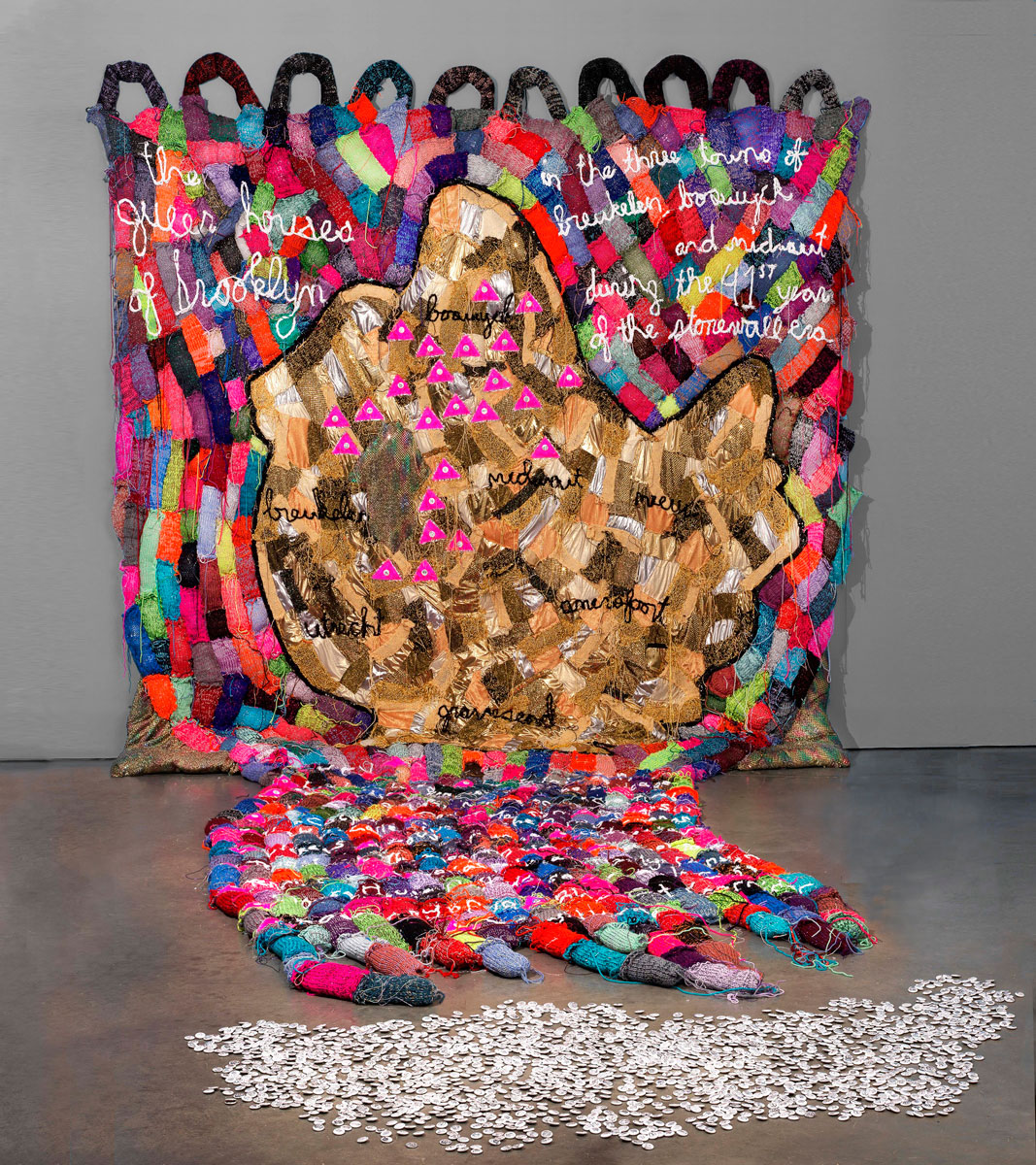

Detail: L.J. Roberts, “The Queer Houses of Brooklyn”

Detail: L.J. Roberts, “The Queer Houses of Brooklyn”

I was overwhelmed by this exhibit. I felt a sort of euphoria that I rarely feel in gallery exhibits. I think it had to do with the sexual heat/energy that emanates from so much of the work, but also from the vibrancy of color. None of this work operates within a minimal aesthetic; most of the work functions with a “more is more” kind of sensibility. Is that a reflection of our times? Are we screaming about our gayness because we won’t hide anymore?

I love hearing that you had such a visceral response to the exhibition. Many viewers of Queer Threads have noted the positive energy–even a visual and emotional vibration–in the space. Color and texture, I think, largely influence this dynamic. The desire to touch fiber work is so strong, and I think that makes viewers aware of their desire to touch and connect on both a physical and communal level. I think this awareness of touch is heightened for queer audiences. Maybe Queer Threads creates a collective moment of Public Display of Affection (PDA)–a feeling so rare in a gallery or institution.

Queer Threads looks and feels warm and fuzzy. Mediums like crochet, quilting, sewing, embroidery, and needlepoint often evoke a sense of comfort that we may have had or seek within the home. Melanie Braverman’s quilt of sometimes playful and sometimes caustic anti-gay slang, for example, questions the notions of a “security blanket” or “home.” Media like macramé riff on the utopian ideals shared by both 70s hippies and contemporary queers, and this invokes a positive sense of the future or self-determination. (On the other hand, Athi-Patra Ruga’s tapestries or Chiachio Giannone’s embroideries remind us that many of these ideas are white and Western.)

Specifically, artists like Larry Krone and Allyson Mitchell openly embrace a “maximalist” sensibility in their practices. Both of these artists also utilize found fibercrafts like granny squares as material in their work, and in doing so, they celebrate the forgotten or uncredited handiwork and create a new sense of community or connection, not unlike Mike Kelly’s monumental “More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid.”

L.J. Roberts, “The Queer Houses of Brooklyn in the Three Towns of Breukelen, Boswyck and Midwout during the 41st Year of the Stonewall Era, (based on a 2010 drawing by Daniel Rosza Lang/Levitsky with 24 illustrations by Buzz Slutzky on printed pin-back buttons),” 2011, Poly-fill, acrylic, rayon, Lurex, wool, polyester, cotton, lamé, sequins and blended fabrics with printed pin-back buttons. Image courtesy of the artist.

L.J. Roberts, “The Queer Houses of Brooklyn in the Three Towns of Breukelen, Boswyck and Midwout during the 41st Year of the Stonewall Era, (based on a 2010 drawing by Daniel Rosza Lang/Levitsky with 24 illustrations by Buzz Slutzky on printed pin-back buttons),” 2011, Poly-fill, acrylic, rayon, Lurex, wool, polyester, cotton, lamé, sequins and blended fabrics with printed pin-back buttons. Image courtesy of the artist.

I got a strong sense of the 70’s and 80’s in this work even though a lot of the work is more contemporary than that. Do you think that comes from the materials themselves (the saturation of synthetic fibers, etc.)? There are specific references to Stonewall, the 1978 original gay flag and the Castro (which I associate with the 70’s and 80’s even though it is still there). The Nathan Vincent piece reminds me of a vintage Falcon or Colt porn set but it also makes me recall the anxiety of the high school locker room. Is the 70’s and 80’s feeling a curatorial sensibility, is it a reflection of purposeful decisions you made?

I’ve joked that Queer Threads looks and feels like what would happen if Punky Brewster Acted Up–and those references alone reveal how I am a child of the 70s and 80s who came into my own queerness in the 90s.

However consciously or not, the aesthetics and politics of those eras inform my process and perhaps attract me to what I see in artists’ work; for example, LJ Roberts reference to the ACT UP pink triangle in their colorful, funky multi-textured piece, “Queer Houses of Brooklyn”…

Interestingly, the earliest works in Queer Threads— Allen Porter’s 1955 needlepoint and Harmony Hammond’s 1971 piece with crochet and painted fabric–were made within the decades immediately before and after Stonewall and both feature a more muted, subtle palette.

I also am fascinated by how non-Western artists in the exhibition use color, detail, and surface to intersect queer identities and ideas with ethnic and craft traditions.

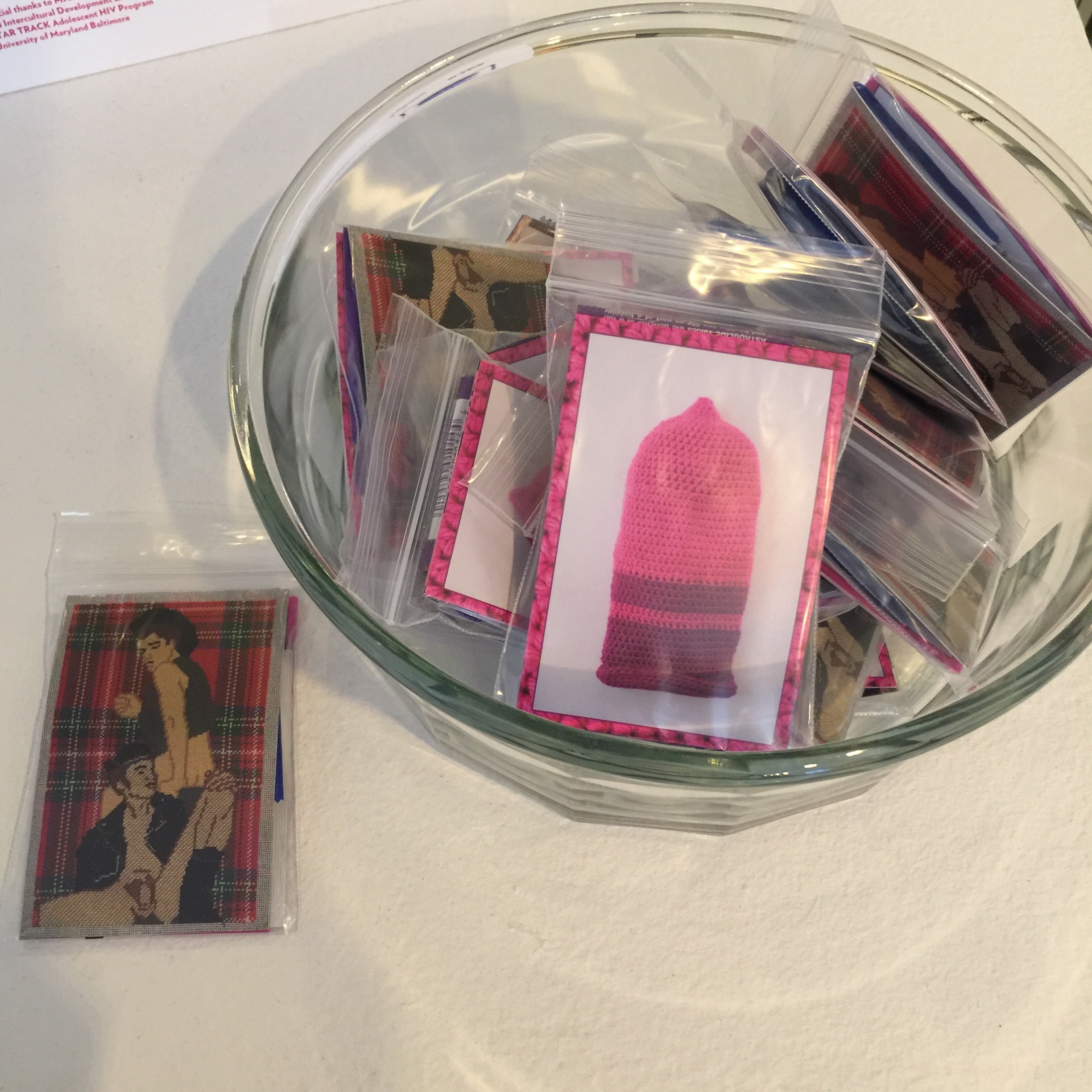

Can you also speak to the takeaways, the condoms (trading cards?) and buttons?

For some time, the organization Visual AIDS has produced a series of safer-sex trading cards called “Play Smart” that feature original work by artists. Visual AIDS invited me to curate a Play Smart series featuring Queer Threads artists in 2014 and nearly 5000 safer sex kits were distributed nationwide then. I’m happy that we were able to reproduce the kits to distribute with the exhibition in 2016.

The buttons in LJ Roberts piece feature drawings by Buzz Slutzky (who also has a series of work in Queer Threads) that feature a crest or coat of arms for every “queer house” of Brooklyn represented in Roberts’ piece. Inspired by the Felix Gonzales Torres’ candy piles or poster takeaways, it is important for Roberts to give viewers a piece of the work to keep with them. It’s always exciting to someone wearing one of the pins. It keeps the spirit of the piece and the exhibition going and growing, and keeps the legacy of queer artists like Gonzales-Torres alive.

I also want to share this link to the Visual AIDS Play Smart trading cards series for more history and context.

There is a catalog forthcoming, can you talk about that as a project and maybe give us a preview of what to expect?

I am thrilled that a companion coffee table book is being published by AMMO books in Summer 2016. The book is designed by Todd Oldham Studios and co-edited by Todd and myself.

It is not an exhibition catalogue per se. Instead, the coffee table book showcases a sampling of queer artists working in different ways with fiber today.

In addition to artists from the exhibition, other artists in the book include Nick Cave, Jade Yumang, Angie Wilson, Cindy Baker, and Josh Faught– as many as we could fit at this point in time in 144 pages.

In total 30 artists are given full-color spreads of their work, and were interviewed by 30 makers and thinkers across art, academia, design, fashion, music and media, including Jonathan Adler, Glenn Ligon, Mickalene Thomas, Justin Vivian Bond, Tim Gunn, Kathleen Hanna, Mondo Guerra, and more.

If resources and interest permit, I’d love to rotate even more interviews and artists on a related website or a second book.

Also, how much did the exhibit change from the NY presentation at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art? Were there changes, replacements, did you have to edit?

Overall, Leslie-Lohman and MICA aimed to keep the 2014 exhibition in tact. Availability and space did influence a few changes.

At MICA, you see different pieces by the same artists due to wonderful circumstances: the pieces originally shown in Queer Threads in NYC have since been acquired by private or permanent collections or are being shown in other exhibitions, so we substituted other work by the same artists.

Since space allowed at MICA, as an extension of Liz Collins’ installation, I now was able to include an excerpt of Sabrina Gschwandtner’s film documenting the Knitting Nation action that produced the massive pride flag Collins presents a site-specific installation here.

Timing proved to be fortunate for other work: discussions and relationships that had been been in development for a few years to include works by Harmony Hammond and Athi-Patra Ruga came to fruition in time for MICA. Hopefully their work deepens the global and historical perspectives in the show.

Conclusions and Favorites:

This is fantastic exhibit with so much to discover that it benefits from multiple visits.

A personal favorite was Sheila Pepe’s “Your Granny’s Not Square,” 2008. The work is a wild, mangled composition made of shoelaces and yarn and creates beautiful shadows.

A personal favorite was Sheila Pepe’s “Your Granny’s Not Square,” 2008. The work is a wild, mangled composition made of shoelaces and yarn and creates beautiful shadows.

John Thomas Paradiso’s “Leather Pansy II,” 2010, uses a small embroidery hoop as a functional frame. The small intricacies of the pansies embroidered on black leather are an evocative, smart contrast. (Leather, thread, and plastic hoop on basswood panel. Image courtesy of the artist.)

“Road to Tennessee,” 2015, by MICA faculty Aaron McIntosh combines a large digital print (sourced from gay erotica) on fabric with skillful quilting and fabric manipulation. The male silhouette is simultaneously on a journey and fleeting into memory.

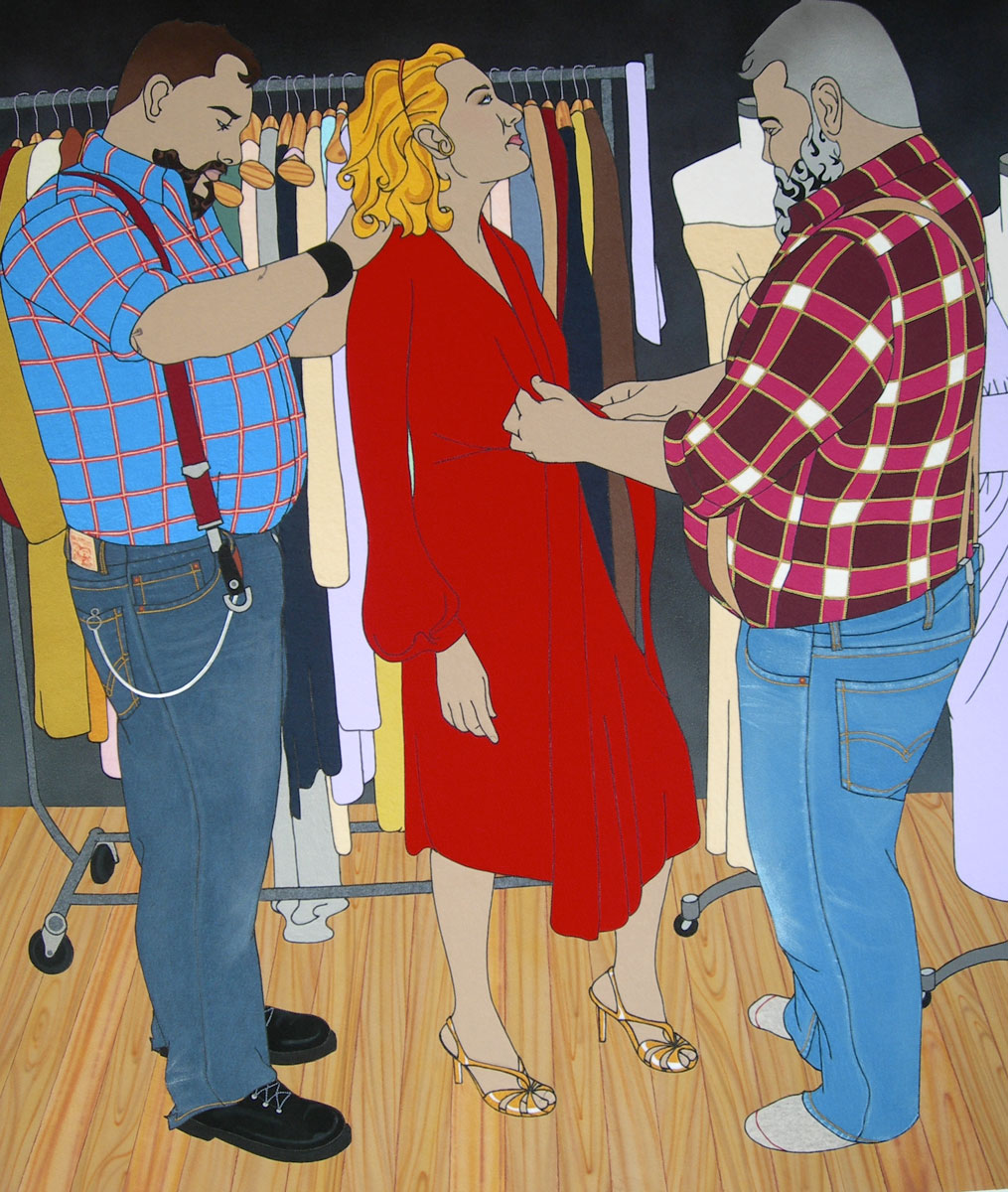

James Gobel’s, “The Fitting No. 1,” is a large scale “painting”, made of felt and yarn, of womenswear designers Costello Tagliapietra. The color is so saturated, but the felt has no sheen, so it looks so flat. Looking at it feels surreal. I love the image of the two sturdy daddy bears fussing over the fit of gossamer high fashion.

Right as you enter the gallery you are confronted by Liz Collins, “Accumulated Pride,” 2014, a piece made of cotton and other yarns loomed during KNITTING NATION performance installations, 2005-2012.

There is a video of some of the performances included alongside the massive pile of a knit rainbow that references the original 1978 gay flag designed by Gilbert Baker in that includes hot pink (referencing sexuality) and turquoise (referencing magic and art). I want those two stripes back in our rainbow pride flag!

Nathan Vincent, “Locker Room,” 2011. Lion Brand yarn over Styrofoam and wood substructure. Image courtesy of Stephen Miller.

Nathan Vincent, “Locker Room,” 2011. Lion Brand yarn over Styrofoam and wood substructure. Image courtesy of Stephen Miller.

Nathan Vincent’s “Locker Room,” 2011, is stunning. At first it might come off as visual joke, it is a complete locker room including lockers, urinals, showers, a drain, and benches that are all made of Lion Brand knitted yarn. But it is not a joke; the piece evokes the weird sexuality and anxiety of locker rooms for gay boys as they become gay men. There are no stalls here; changing bodies would be in full view in this locker room. Glances, shame, thwarted attempts at cruising, the brutality of nakedness, fodder for fantasy… it’s all in this piece.

The curator also asks us to read this piece, and all of the included works, from a feminist perspective. In a Hyperallergic interview he said “I don’t think one works with fiber or craft techniques in their art without being a feminist.”

Go see this exhibit and attend and participate in the robust public programming that accompanies it. It feels very rare to have this much queer fiber based art work here in Baltimore. The show is vibrant, it pulses with color and urgency and speaks to a wide range of queer experiences.

Author René Treviño is a Baltimore-based artist and professor. His visual work challenges traditional ideas of race and sexual orientation. He is represented by the C. Grimaldis Gallery in Baltimore and the Erin Cluley Gallery in Dallas, TX.

John Chaich (curator) is a designer, writer, and curator living in New York City. His recent exhibition, Mixed Messages: A(I)DS, Art & Words, for Visual AIDS debuted to critical acclaim in The New York Times and Artforum before traveling to DC to coincide with the International AIDS Conference. He has written on art and pop culture for BUST and Art & Understanding magazines and has contributed catalogue essays for PPOW Gallery. On the Web and on Twitter: ChaichCreative.

Links: MICA Queer Threads exhibitions page and Leslie-Lohman Museum

Additional Programming for Queer Threads:

Queer Threads, Common Ties: An Intersectional Dialogue with Aaron McIntosh Thursday, Feb. 4, 7–9 p.m.

Fox Building: Decker Gallery, 1303 W. Mount Royal Ave.

Queer Threads Unraveled: A Roundtable Discussion with Scholars Julia Bryan-Wilson, Ph.D., associate professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at the University of California, Berkeley and Ann Cvetkovich, Ph.D., Ellen Clayton Garwood Centennial Professor of English and professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Texas at Austin

Sunday, Feb. 7, 1–3 p.m.

Brown Center: Room 320, 1301 W. Mount Royal Ave.

Harmony Hammond, Materially Queer

Wednesday, Feb. 10, 7 p.m.

Brown Center: Room 320, 1301 W. Mount Royal Ave.

Invasive: Amassing Southern LGBTQ Stories, Hands-on Fiber Project with Queer Threads Artist and Aaron McIntosh

Sunday, Feb. 14, noon–6 p.m.

Brown Center: Leidy Atrium, 1301 W. Mount Royal Ave.

American Craft Council and MICA Speaker Series: Elissa Auther, Museum of Arts & Design

Wednesday, Feb. 17, 6–8 p.m.

Lazarus Center: Auditorium, 131 W. North Ave.

Artists Talk Saturday, March 5, 1–3 p.m.

Fox Building: Decker Gallery, 1303 W. Mount Royal Ave.

Featured artists Jesse Harrod (Philadelphia), Rebecca Levi (Brooklyn) and John Thomas Paradiso (Brentwood, Md.) join fellow artist and MICA Fiber Department faculty Aaron McIntosh for an intimate gallery talk with curator John Chaich.