Film Review by Angela N. Carroll: New African Film Festival Feature Lamb, directed by Yared Zeleke

I write this five days into the 2016 New African Film Festival running March 11th-18th at the AFI Silver Theater, in a semi-hallucinogenic trance from ingesting hours upon hours of films. Films from Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sudan, South Africa, Burkina Faso Senegal, Algeria, Guinea, Tanzania, Mauritius, Rwanda, Namibia, Kenya, Uganda, Mali, Niger, and Ghana.

I have watched each film in this festival as giddily as a child in a video game arcade. Engorged my eyes; iris expanding in exquisite ecstasy. I am high from the vast complex perspectives of the African Diaspora that American theaters rarely screen. This is the first review of a series covering festival films that I consider exceptional.

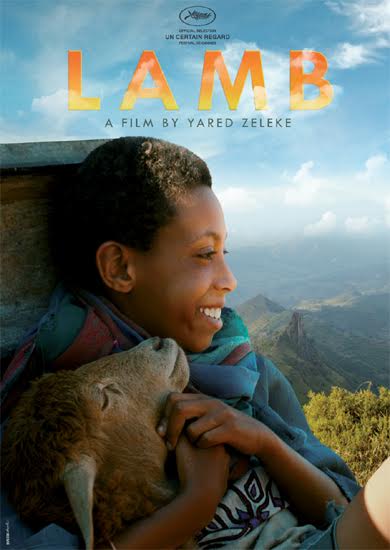

Yared Zeleke’s debut feature Lamb is a stunning drama about Ephraim, a young boy and his best friend Chuni, a lamb gifted to him by his late mother. Some of the film’s most beautiful moments occur during silent wide-angle montages of the boy and the lamb walking through the southern countryside of Ethiopia.

Yared Zeleke’s debut feature Lamb is a stunning drama about Ephraim, a young boy and his best friend Chuni, a lamb gifted to him by his late mother. Some of the film’s most beautiful moments occur during silent wide-angle montages of the boy and the lamb walking through the southern countryside of Ethiopia.

Lamb begins with an extreme close-up of a child’s hand petting thick reddish-brown wool. Cut to lush green rolling hills. Ethiopia’s landscape is as alive as the boy and his lamb. Josee Deshaies’s dynamic cinematography renders every shot a sprawling epic celebration. The aesthetic of the film is breathtakingly beautiful from beginning to end.

I was unsure about whether I would enjoy watching the relationship between Ephraim and Chuni develop, but Zeleke’s script and direction made for a believable and engaging exchange. Ephraim, played by the young talent Rediat Amare, is adorable. The connection between Ephraim and the lamb made the audience “awwww” more times than I could count. Envision a cute kid cuddling with a lamb twice his size, and you will understand the reaction. Chuni is Ephraim’s only friend and a prized keepsake from his deceased mother. Abandoned by his father, he is left in the custody of his uncle. The film follows Ephraim as he searches for ways to save Chuni from becoming the main dish at his uncle’s holiday festival.

Ironically, Ephraim is an accomplished cook, which catalyzes a major rift between him and his uncle about the activities a boy should pursue. Zeleke portrays a country in ideological flux. To help raise money for the family, Ephraim offers to make lentil samosas to sell at market, to which his uncle chides Ephraim and his father for raising a sissy instead of a boy. Nearly 71% of Ethiopia’s population is under the age of thirty. Belief systems concerning modernity and tradition, gender roles and equal education are shifting with the emergence of a generation more open to change.

It is Ephraim’s aunt who notices his talent and an opportunity for additional income. She allows him to cook in secret under the condition that he contributes those earnings back to the family. Ephraim partially honors this agreement retaining the majority of his earnings in preparation for his and Chuni’s escape back to his fathers unoccupied home. Ephraim is intelligent and contemplative, but his actions are those of a child, self-obsessed and inconsiderate of the needs of the whole. When Ephraim’s youngest cousin, the family member most eager to eat Chuni, becomes devastatingly ill, the family cannot afford to buy her medicine.

Ephraim must decide whether to give up the money he has been saving or run away. Lamb explores Ephraim’s maturing as he learns to balance the needs of his family with his own desires for freedom. He marches to the beat of his own kebero even while his family and community consider him and his pastimes with Chuni oddly out of sync with cultural and societal norms.

Ephraim’s cousin Tsion, is similarly outcast– the last unmarried teenage girl in her village. Tsion spends her time listening to men at cafes as they discuss politics. She is only able to access newspapers at those meetings, and covets them preferring to read instead of help her aunt cook. Her aunt is horribly embarrassed by Tsion’s dismissal of her domestic duties, and feels the community will shame them if Tsion refuses to marry. Despite family pressures, Tsion courageously bucks against expected conformities.

Zeleke cleverly incorporates humor throughout the film to challenge sensitive cultural taboos. In one particularly poignant scene, Tsion pours a foul smelling liquid from a bucket onto the family garden. The uncle bellows in horror when he learns that the girl has used the family’s urine as a fertilizer. “Why do you want to bring shame to the family?!” he moans. Tsion has learned about this new agricultural skill from the newspapers she is vehemently warned not to read. It is only after Tsion runs away to the city of Addis Ababa that her family realizes the value of her literacy– the garden flourishes.

Lamb was an exceptional film, successful in its critique and contextualization of emerging Ethiopian discourse. The juxtaposition of Ephraim’s extreme love for his lamb framed against the backdrop of crippling famine and poverty in the countries southern region grounds the film. Yared Zeleke continues to advance the mission and style of third cinema and if Lamb is any indication of his skill and vision, I eagerly await future projects.

The 2016 New African Film Festival, March 11th- 18th at the AFI Silver Theater.

Author Angela N. Carroll is an artist-archivist; a purveyor and investigator of contemporary culture.