Joseph Shaikewitz on You Can’t Take It With You at Ballroom Gallery

A screenprint adorned in a broad pattern of white and gray stripes sits atop a shallow pile of more than a hundred like it. The piece in question—Isabel Rosen-Hamilton’s “Stack I”—rests inconspicuously in the middle of Ballroom Gallery’s current exhibition You Can’t Take It With You.

As a mound of multiples, this work screams out to an important predecessor: Félix González-Torres and his knee-high stacks of printed handouts. In “Untitled (The End)“ (1990), to take one generative example, the artist solicits viewers to remove the topmost, gray-bordered page from the vertical mass and transport it away from the galleries, offering a poignant and socially attuned allegory for loss with the promise of renewal.

Rosen-Hamilton approaches “Stack I” through a discrete set of conditions. Her placid arrangement contains a laser-cut and oblong cavity that recedes through the core and invokes a sculptural vocabulary of dimensionality, surface treatment, and negative space.

In the aftermath of González-Torres’ legacy, “Stack I” subverts the rhetoric of easily distributable printed matter through a pronounced incision into an otherwise recognizable and widespread form—that is, the stack of paper as in invitation to consume material and information. Here, each page totters between distinctions of sculpted and printed—refusing (importantly) to settle on one over the other—and responds to the coded language of the latter. The pile not only inherits the associations of González-Torres’ communal gesture, but responds to it in a way that seems to take the exhibition title as its anthem: now, you can’t take it with you.

Since opening last October, Ballroom Gallery has produced a series of ambitious and sharp exhibitions; this fifth and current installation is no exception. Organized by Rosen-Hamilton and Gabriella Grill, two of the exhibiting artists in the show, You Can’t Take It With You highlights a smart arrangement of work that goes beyond a collapse of the boundaries between printmaking and sculpture to offer new situations for understanding the nuances of their intersection.

This blurring of frontiers has been on the public radar for decades now; it was most notably articulated in 1979 when Rosalind Krauss published her seminal essay “Sculpture in the Expanded Field.” However, across Ballroom Gallery’s exhibition, the confrontation of traditional sculpture’s rigidity and durability with printmaking’s marked mobility and mutability is taken as a prerequisite. In turn, the works on view take this historically established junction of media to new heights in a way that transcends mere formal experimentation.

In addition to “Stack 1”, Hamilton-Rosen includes a ceiling-to-floor inkjet print titled “Crumpled Roll”. The sweeping expanse of paper graphically depicts a wrinkled surface whose creases and shadows make up a seemingly infinite scroll of visual disarray. At each edge of the image, two clean margins reinsert the printed quality of the work and underscore the artifice of the complex trompe-l’œil. Nevertheless, the self-referentiality of this illusion—illustrating an unworkable sheet of paper atop its flat and standard analog—reads not as disingenuous, but rather as a contained reflection on the permeability of value and longevity.

The expansive surface bears an image of that which would typically be discarded or deemed unusable, but here the work as a whole strives to replicate the undesirable through exacting precision. The visual exists as a layer upon itself—part of an additive process that underscores the fluidity between image and material. As similarly seen in her adjacent stack, Rosen-Hamilton deploys the guise of sculpture as a means to intercept and elevate the fate of printed matter, using the former to imply an escape from a throwaway identity while coolly slipping into a more everlasting lifespan.

Zack Ingram engages comparably subtle shifts that translate the two-dimensional into a sculptural realm with the inclusion of two subdued yet intriguing untitled works. In each example, it is the printed image’s occupation of space that shuttles the form into objecthood. The first work to greet the viewer consists of a checked gradient screenprint on a peculiar sheet of mustard colored felt. Situated on the floor, the print bears the weight of a steel bar that bisects and compresses the planar object. The introduction of a heavy sculptural component cements the folds and furrows in the felt, fixing a composition that begs to unfurl with the involuntary ease of arms outstretched mid-yawn.

Overhead and tucked away behind a corner, a second print by Ingram elucidates the corporeal impetus of these spatial images. Pinned between the intersection of two walls, a swath of white cotton offers a cropped and slightly off-center depiction of an anonymous body with a clearly clenched fist set off in contrast from the gray-clad figure. While the scale of the work enforces the idea of an immobile flag, the tightened hand conjures notions of rebellion. In the context of a screenprint nailed at two corners into wrinkled stasis, these ostensibly divergent themes coalesce into a potent visual desire for anarchic upheaval amid rigid ordering structures.

Should we read the body through the screenprinted components in both of Ingram’s works, it is the manifestation of a body rendered passive by these controlling and cumbersome sculptural interventions. Rather than a bleak outlook, however, the artist employs the image itself as a conduit for defiance—displaying meaning and opposing the censorship of a pleated surface. Where Hamilton-Rosen might envision the sculptural as a means of granting legitimacy, Ingram pauses this inquiry to contemplate the polemics of power and the resistance of control. Through the latter, this outcry may be at its core soft spoken, but it reveals itself slowly and with willful restraint.

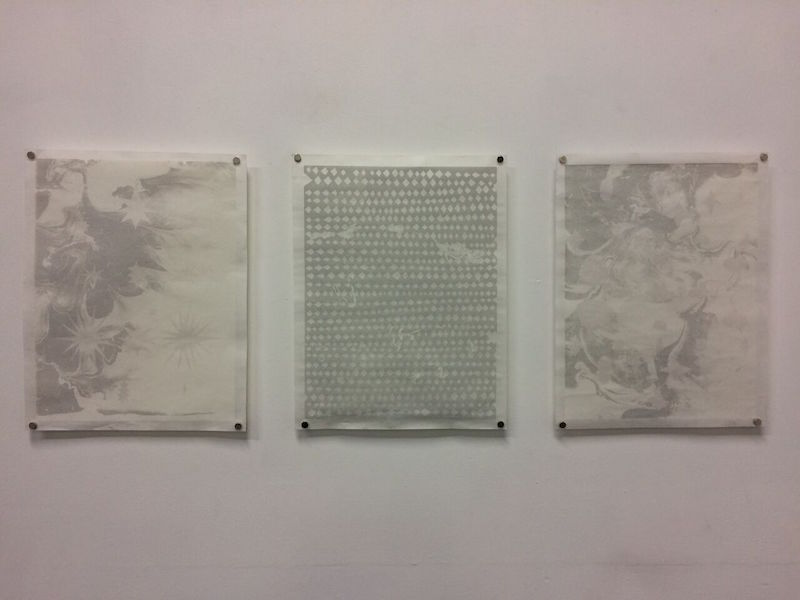

The remaining artists in the exhibition approach the overlying theme with a slight inclination towards whimsical experimentation. Gabriella Grill contributes two distinct bodies of work to the space. “Cut Through Marble (I-VIII)”, displayed in two groupings across the gallery, is a series of lithographs that seemingly describe one thin strata of marble after another. The stone’s unique and delicate patterning—which reads like drifting white and gray liquid frozen in geological time—is interrupted by motifs of starbursts and diamonds.

In my reading of the work, this highly graphic intervention disturbs an otherwise effective musing of material. The base layer of marble-like pattern on its own presents an already intricate reflection on the presumed permanence and durability of the naturally occurring material. Each printed variation appears as if a paper-thin sliver of a larger slab of rock, an effect that is smartly reinforced through the use of translucent mulberry paper and the positioning of each print slightly away from the wall. The lithographs intimate a sensation so separate from our usual encounters of a historically totemic material to grant a moment of suspended fragility, but this illusion at large feels disrupted by the optically flat shapes worked into the design.

“Pyramid Nine”, a floor-bound sculpture also by Grill, composes a more succinct vision of graphic patterns assuming a sculptural edge. The work consists of a pyramidal wooden structure that reads much like a stark winners’ podium. Draped across each step, a linen screenprint alternates between empty space and a square of Benday dots that rests atop each horizontal tread.

Skillfully fabricated as one stretch of cloth, the print cloaks the underlying form, tucking into its corners and bundled into a neat roll of excess at each end. The work sets up a supposed hierarchy of scale as the circular patterns increase in size with each heightened level, but such a social ordering is revealed to be an illusory endeavor. The determination of which print occupies the uppermost echelon is predicated on a superficial and arbitrary condition of geometric largeness, as if Grill is collapsing the rhetoric of social power upon itself.

A scattering of wall pieces from Jackie Riccio rounds out the exhibition. While their relationship with traditional printmaking is relatively more far removed, they effectively hold their own while adding a welcome contrast to the abovementioned interactions of print and sculpture.

A scattering of wall pieces from Jackie Riccio rounds out the exhibition. While their relationship with traditional printmaking is relatively more far removed, they effectively hold their own while adding a welcome contrast to the abovementioned interactions of print and sculpture.

Riccio’s work is hard to pin down: an amalgam of lithography, textile scraps, sculptural adhesions, and found objects, the resulting pieces don’t just deny classifications of medium—they taunt them.

In “Free-S”, I, an aluminum printmaking plate layers a muted lattice and a gradient field with a stripe of lace and an offcut of fabric bearing a confetti-like design. A metallic painted foam object resembling a handle grips onto the surface, as if facetiously inviting the viewer to remove the work from the wall and transport it away. Elsewhere in “Free-S II”, a colorful assortment of candy licorice overlays a similar visual model, coming off as both celebratory and tongue-in-cheek.

Riccio’s “Land of Plenty, Land Scene One” is a veritable feat, scattering an impressive array of textiles with objects both sculpted and found. A floral fabric sits within a smashed aluminum tray; an amorphous spray foam scribble bleeds into the flat surfaces below; a nondescript milk carton sprouts a yellow branch; and a sewn pouch expels a handful of iridescent opal shred. Despite this panoply of objects and ensuing associations, the work remains at once conceptually cohesive and visually verbose. Riccio’s treatment of found objects—be it prosaic debris or leftover scraps of fabric—calls attention to the human origins and fabrication of these commercially available objects.

Through a heavily handmade quality, the artist equates (for example) a sheet of carefully drawn lines to a run-down wire fence as if to posit her refuse of choice as bearers of a history of use and production. This foregrounding of the human nature of everyday things may be counterintuitive to the apparatus-heavy field of printmaking, but this is ultimately to its very benefit; the effect, as many of the bordering artworks seem to conceal, stresses the interpersonal beginnings of printmaking and the versatility of its substance.

If You Can’t Take It With You falls short in any regard, it’s in a curatorial grouping that can strangely enough feel too cohesive at times. While there is a wealth of conceptual depth to each individual piece and to the exhibition at large, a greater variety of aesthetic motivations and tension between the works could deepen and expand the meaning derived from piecing together the show. The installation demonstrates great restraint, but this tightened grip over any margin of error periodically boxes the artists in.

In any case, the exhibition is without question effective in weaving together an original image of the interactions between print and sculpture. Rather than merely note this seemingly oppositional convergence of media, You Can’t Take It With You traces an intricate narrative that oftentimes treads over the consequences of this expanded field in broader social circles. Leaving the gallery, I pick up a corresponding object list detailing the works on view. The cardstock on which it’s printed feels noticeably heavy in my hands, embedded with a certain gravitas—if only momentarily—until I fold it twice, tuck it into my pocket, and continue on my way.

Author Joseph Shaikewitz is a Baltimore-based writer and curator from St. Louis, MO. He is the Gallery Manager at Hamiltonian Gallery in DC and a graduate of Johns Hopkins University.

Images courtesy of Ballroom Gallery.