To Be Black in White America, A Group Exhibition at Galerie Myrtis

by Angela N. Carroll

What does it mean to be black in white America? Well, it all depends on who you ask.

I saw barefoot families, I saw drug money buy churches, I saw hoop dreams spark and fade. I saw all types of dreams spark and fade. I saw house raids, I saw families evicted, I saw AIDS spread, I saw thousands made and lost right in the middle of the place where cops enforce, terrorize and collect — I saw it. I saw it all.

– D. Watkins in The Cook Up: A Crack Rock Memoir

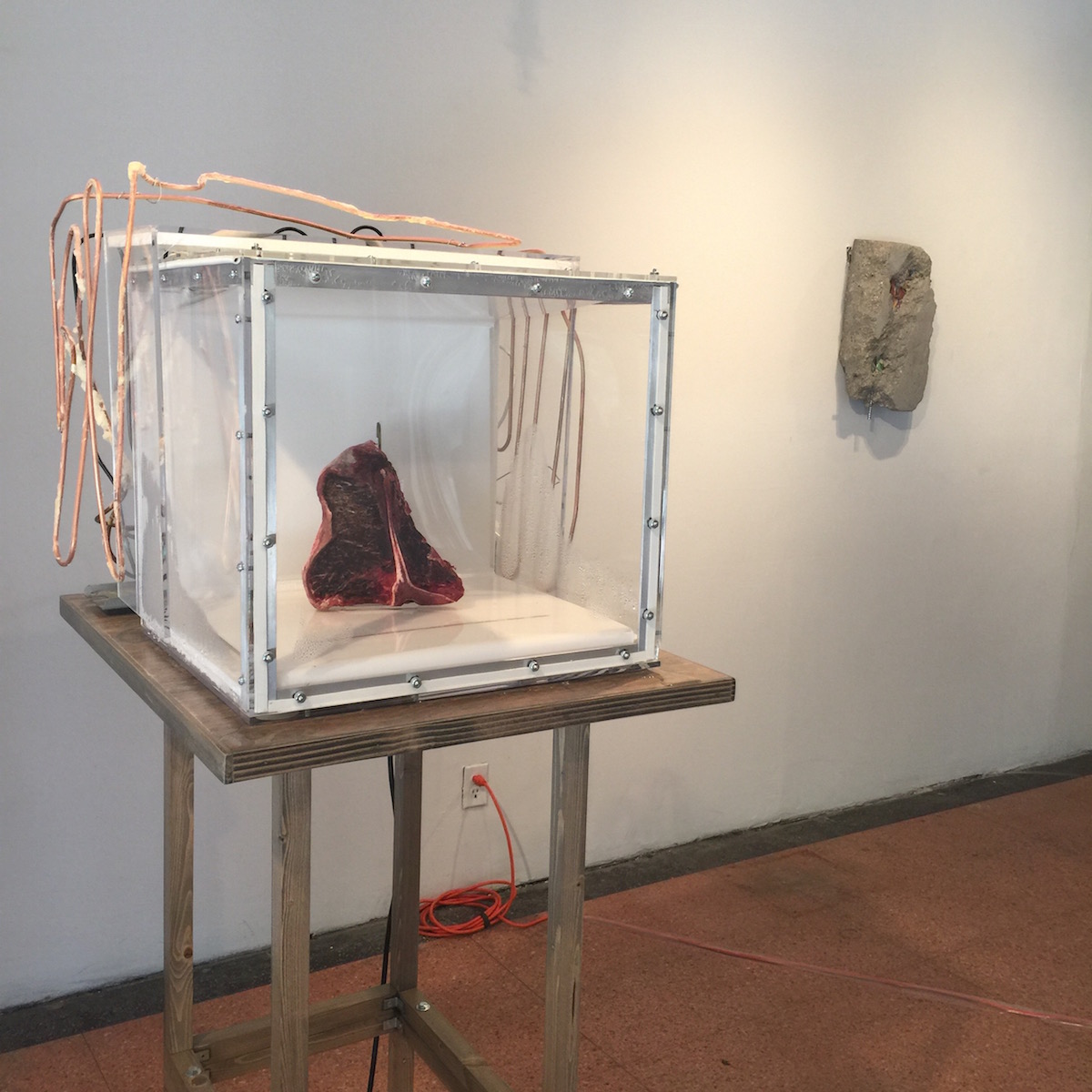

Linda Day Clark

Linda Day Clark

Class and education factor into definitions and experiences, but can not separate one from their blackness, the identifier that will mark one’s accomplishments and failures in the United States of America. Community and family contribute to one’s foundational sense of self but can not shield one from the fears or microaggressions of bigots, the fanatical rhetoric of fascists, homophobes, xenophobes, religious zealots, or general ignorance.

If you understand that race is a concept, a construct, then you will also understand the myriad systems that reinforce those constructs: white supremacy, privilege, capitalism, the prison industrial complex, the medical industrial complex, voter ID laws, reproductive rights legislation, and so on.

To be black in white America is the knowing that anybody that is not white will be othered, will be shamed, will have a legacy of subjugation, will have to battle for better. To be black in white America is the daily acceptance that you will confront systems that interrogate and refuse to accept your humanity; that refuse to respect your rights, your privacy, your life, liberty, and justice. To be black in white America is living with undiagnosed PTSD. The cyclical burying of innocents. The cyclical strategizing of freedom movements.

The group exhibition To Be Black in White America at Galerie Myrtis features a collection of artists whose work unflinchingly grapples with issues of power, identity, race, and class. Wesley Clark, Larry Cook, Linda Day Clark, Oletha DeVane, Nehemiah Dixon III, Susan Goldman, Curlee Holton, Wayson R Jones, Jeffrey Kent, Wendel Patrick, Jamea Richmond-Edwards, and Stephen Towns each contribute critical, timeless inquiries which focalize the unsettling realities of black American experiences.

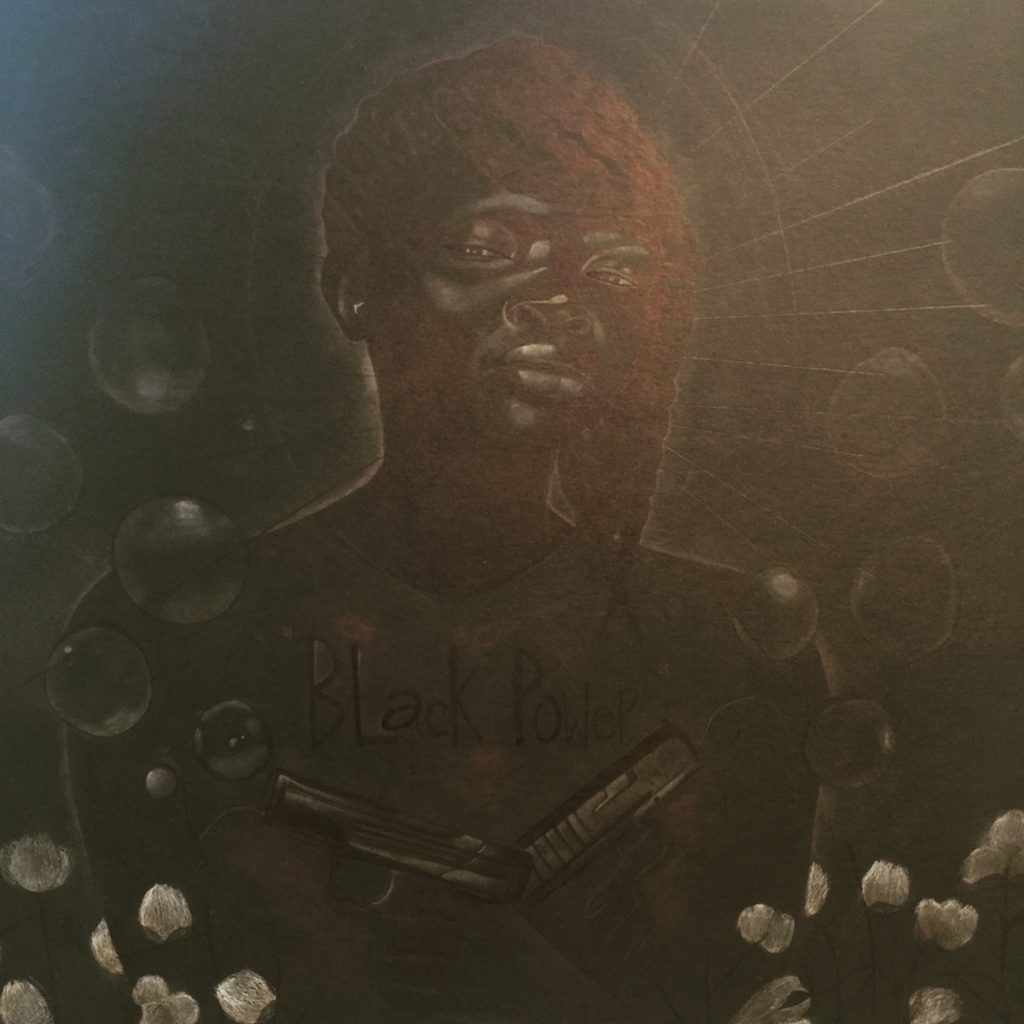

Jamea Richmond-Edwards Guns, Bubbles and Black Power, 2012

Jamea Richmond-Edwards Guns, Bubbles and Black Power, 2012

Guns, Bubbles and Black Power by Jamea Richmond-Edwards is a sensitive portrait of a black woman etched in ink and chalk on black canvas illuminated by fluffs of white cotton sprouting around her torso and bubbles floating around her head. The woman holds two pistols. The pistol’s frame the slogan of her t-shirt, “Black Power,” which is obscurely printed across her chest. Despite the lack of contrast in the image, she glows a radiant charcoal black. Astral black. Blue black. So black you have to move closer to the image, then step back to gather all the details.

She offers a slight smile, and her eyes connect with yours, while a faint halo and residual rays crown her. The artist has been experimenting with black on black portraits for the past five years. The technique forces a direct and visual engagement with the work and cheekily plays with the concept of creating “black” art. Edwards admits that she developed the style as a means to “make the art blacker.” In context with the group exhibition, the work is one of just a few that depict women. The vast majority of the exhibition focalizes struggles to humanize black male Americanness. Guns, Bubbles and Black Power stands in a category all its own.

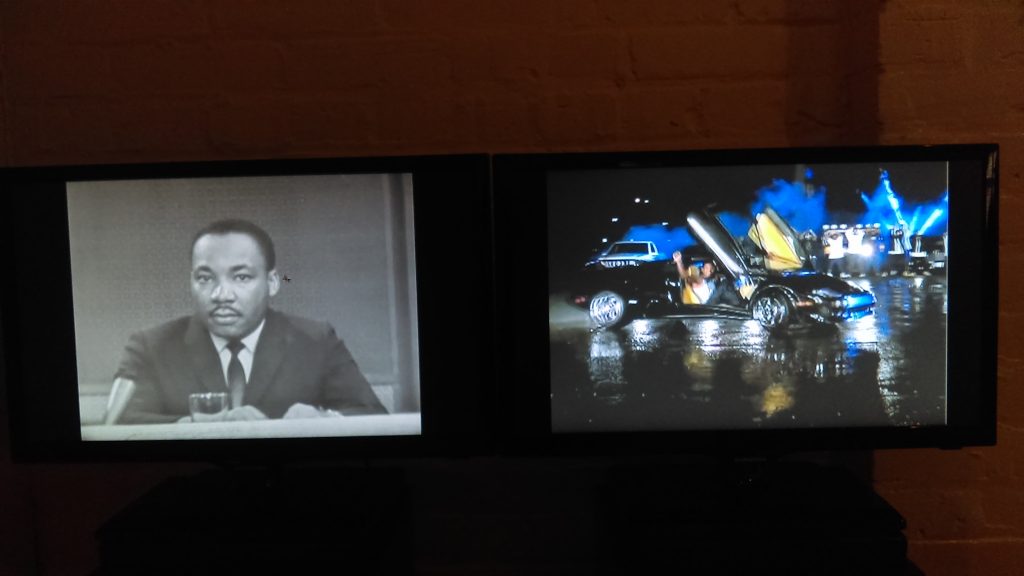

Larry Cook- M.L, 2012 and Picture Me Rollin, 2012

Larry Cook- M.L, 2012 and Picture Me Rollin, 2012

In the back gallery, two monitors installed on top of pedestals display muted video footage. The left monitor loops an excerpt from a speech by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Cook does not disclose the name of the speech, and provides no means to listen to the audio, but you can read his lips and imagine that Dr. King is speaking about black liberation, desegregation, and civil rights. Though the speech is silent, the familiarity of the image of the civil rights leader professing from podiums has been immortalized in the American consciousness as a nostalgic relic of national progress, while his silence functions like a metaphor.

The right monitor loops an excerpt from a music video. A black man spins donuts in a Lamborghini. One hand is on the wheel, the other is raised out of the open suicide doors. Crowds of onlookers cheer and roll their arms to mimic the whipping motion of the car. Chains and teeth gleam in the night. Melting tires smoke. The footage cuts to a young boy driving a mini toy lambo, then cuts back to the man who happily, aimlessly, rolls, stunts, and flosses for the crowds.

The juxtaposition of the two videos, not originally rendered as a dual composition, reminded me of the Boondocks season one episode nine, Return of the King, which imagines Dr. King awakening from a 40 year coma after a failed assassination. A troubling and witty hilarity unfolds as Dr. King assesses the impact and progress of the civil rights era for African Americans in a world he no longer knows. M.L. and Picture Me Rollin examine the state of post-civil rights era black America. Cook explained that the installation “speaks to the false sense of progress, and the American dreams that were never realized” despite the struggles of the civil rights era. The installation successfully critiques those perceived losses and gains.

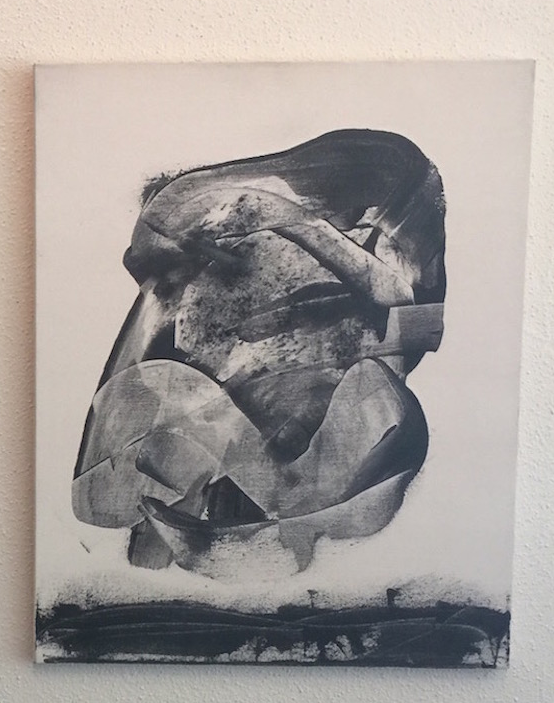

Wayson R. Jones- Black President series, 2012 (Black President, Crying Out, Incarcerate, Saint)

Wayson R. Jones- Black President series, 2012 (Black President, Crying Out, Incarcerate, Saint)

Wayson Jones’ Black President Series is a collection of five acrylic, gesso and powdered graphite canvases. Jones created the works as a “reaction to the extremity of backlash of President Barack Obama’s election.” The collection are figural, distorted, meta-abstractions that activate white, black and gray values in subtly disturbing ways. The hypnagogic forms that emerge from densely layered palette knife strokes explode and contort on the canvas.

The series blatant black, white and gray palette elicits the polarized and schizophrenic theater of American politics. Like a rorschach ink blot, the impressions are defined by the psyche of the viewer. Where one patron saw a screaming face, another saw clusters of frenzied orbital atoms. Like life imitating art imitating batshit crazy political rhetoric, the Black President series visualizes the angst and cacophony of our times.

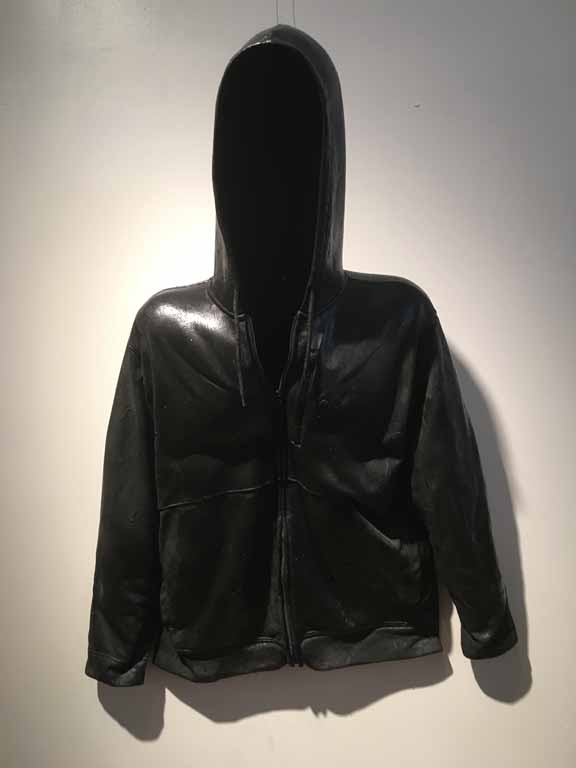

Nehemiah Dixon III- Suits of Armor series, 2013-2014 (Hoodie 1-5), More pictured below

Nehemiah Dixon III- Suits of Armor series, 2013-2014 (Hoodie 1-5), More pictured below

This stunning collection was constructed of five textiles chemically treated to stand as lifesize sculptural pieces, and together as an installation. If the Suits of Armor series had a soundtrack it would be “Boogie Man” from Yasiin Bey’s (formerly known as Mos Def), grossly slept-on second album, The New Danger.

On it Bey croons,“See me, want me, give me, trust me, feed me, fuck me, love me, touch me. This whole world is cold and ugly, what we are is low and lovely. I am the most beautiful boogie man, the most beautiful boogie man. Let me be your favorite nightmare, close your eyes and I’ll be right there.”

Suits of Armor is a startling reminder about the pathology of fear that dehumanizes men of color: boogie men, creeping into the subconscious of privileged bodies. Dixon’s hoodies are ominous hyper-realized manifestations of that fear and its resultant violences.

Shortly after the Oscar Grant verdict, Nehemiah began a year long experiment with materials to give life to the hoodies and give them “as big of a presence as I could get.” The resultant hoodies are “meant to scare you, meant to be intimidating.”

I was surprised by how alarming the series was, not just because the hoodies were rendered to look like they could hop off the gallery wall, but primarily because of the ways the hoodies triggered memories about the countless tragedies against men of color who have been killed while wearing them. A hoodie made of cotton with a basic shape, black color, no flash or flare becomes a phantom, evoking all of the ghosts of unarmed men, whose assassins remain at large.

The Suits of Armor work as supernatural talisman that simultaneously shield wearers from attack and inherently catalyze it. The attire worn by men of color prompt privileged bodies to stand their ground, stop and frisk, or generally assume one’s ill intentions. The series is an emotional and brilliantly executed appraisal of supremacy and the propaganda of fear.

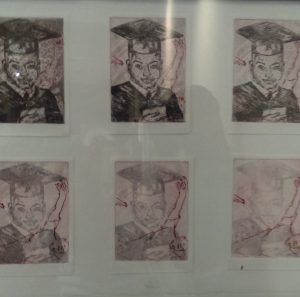

In an extreme contrast, Curlee Holton presents six small etchings, almost like yearbook photos, framed together in two rows of three. The first image shows a crisp dark portrait of a black male in full graduation regalia. The young man smiles at the camera as he holds his diploma or degree. Each subsequent etching progressively fades the graduates image and reveals a fallen figure and a gun. The last image privileges the fallen body and the gun. The graduates portrait dissolves into the background.

I thought back to a sobering excerpt from Ta-Nehisi Coates Between the World and Me, in which he describes the heart-breaking trajectory of his friend’s life. Though his friends parents provided their child with the greatest educational opportunities, though he graduated with the highest marks, and was beloved by his community, none of those accomplishments guaranteed the safety of his body.

None of the accomplishments were enough to save his life. Fear of his blackness superceded his intelligence, his humanity. Coates offers this thought about black experiences in America:

“Perhaps struggle is all we have because the god of history is an atheist, and nothing about his world is meant to be. So you must wake up every morning knowing that no promise is unbreakable, least of all the promise of waking up at all. This is not despair. These are the preferences of the universe itself: verbs over nouns, actions over states, struggle over hope.”

Holton’s Promise also reminds us that nothing is promised for marginalized bodies.

Wendell Patrick The Barber’s Chair

Wendell Patrick The Barber’s Chair

Wendel Patricks’ four large black and white photos celebrating the everyday intimate interiors of black life that were scattered throughout the gallery brought a refreshing balance to the exhibition. To solely interrogate the abject, and not make space to exhibit the humanity that thrives in spite of supremacy would have created a lopsided statement.

The legacy of black experience in America is one of innovation, family, and persistence as well as struggle. To not feature the humanity of everyday experiences like The Barber’s Chair, 2013, that shows a young boy getting his haircut or Father and Daughter, 2015, (pictured at top) that peeks in as a toddler stretches across the broad back of her father to wraps her arms around his neck, perpetuates the stigma and assumption that struggle is inherently and wholly a reflection of black conditions in America and the diaspora.

But I write this a few hours after Lor Scoota has been shot. I write this a few days after Freddie Gray’s death remains unconvicted. The realities of our time are undeniably heavy.

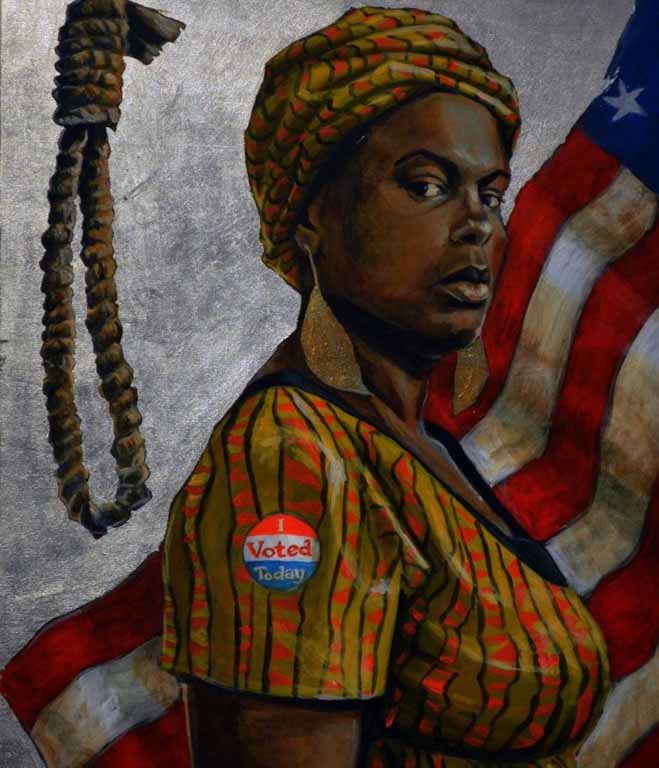

Stephen Towns’ I Wish it Were That Easy, 2014

Stephen Towns’ I Wish it Were That Easy, 2014

Stephen Towns’ I Wish it Were That Easy, 2014, featuring a defiant portrait of a woman wearing a “I Voted Today” sticker, while a noose hangs at her back and the American flag waves at her front, is a poignant declaration that to be black in white America is and perhaps will always require a double consciousness, will always be an active negotiation for rights, for liberties, for humanity.

To Be Black in White America at Galerie Myrtis is a dense collection of devastating and beautifully executed deconstructions about being black and American– about being citizens in a country that does not equally advocate for basic civil liberties, and the joys and heartbreaks that those inequalities manifest.

****

To Be Black in White America is on display at the Galerie Myrtis June 25 – July 30, 2016.

Author Angela N. Carroll is an artist-archivist; a purveyor and investigator of contemporary culture.