A conversation with Elena Volkova on Penumbra, her solo exhibit at Stevenson University by Ian MacLean Davis

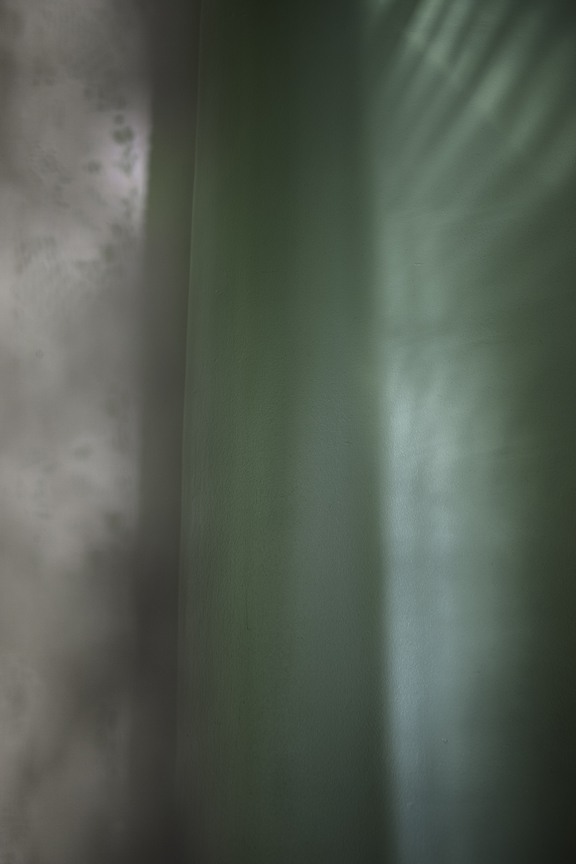

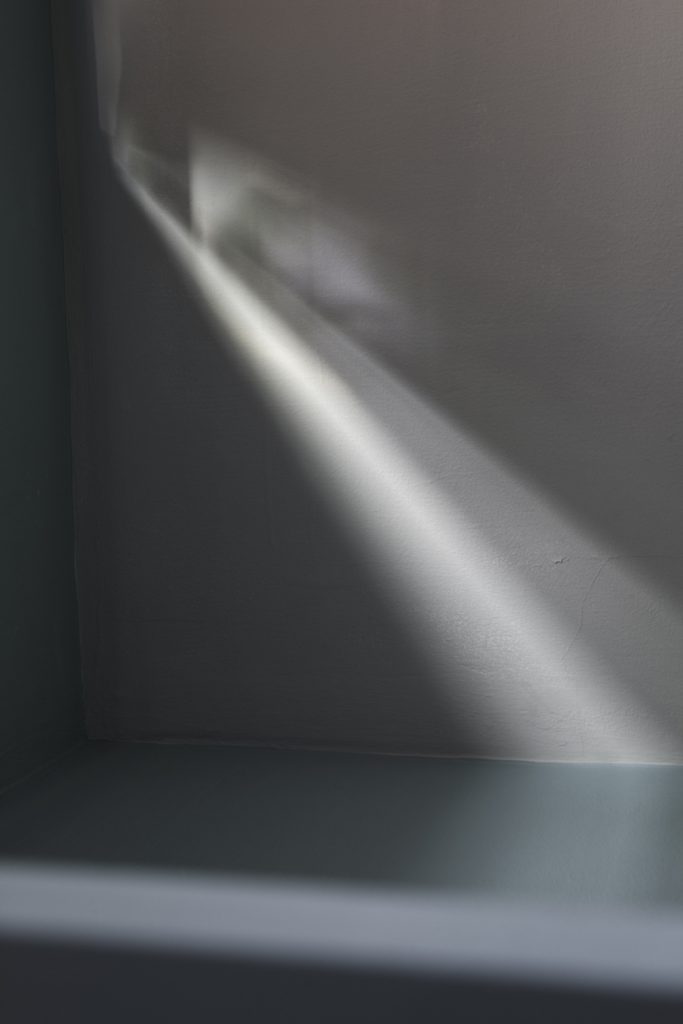

Penumbra, referring to the area of transition between light and shadow, is a series of photographs by Elena Volkova that explores the concept of becoming. The images—observations of the ordinary, commonplace, and familiar domestic spaces—invite the viewer to examine the subtle manifestations of the Everyday.

BmoreArt: Could you talk a little bit about how this body of work started?

Elena: I’ve always paid attention to light. In general my work is about paying attention. A couple years ago, I had a baby, and had to spend a lot of time at home caring for a newborn. And when you are forced to live within a certain perimeter and don’t have much life beyond it, you start paying much more attention to your immediate environment.

I don’t like getting into personal things… it’s somewhat uncomfortable to talk about this because I feel like my work has always been driven from a conceptual place and less so from personal, but this work may be different. Someone used the word “empathy” when discussing it, and I’m trying to figure out for myself whether it is possible to do work that does not come from a personal place; I’m having difficulty explaining how this work started because I’m reluctant to get into “psychology” and emotional responses that drive it.

That’s interesting. How do you mean “empathy?”

Empathy is a human experience through which we can relate to and feel for one another. I think that empathy can speak through the intellectual as well, but often purely conceptual work becomes as good as the artist is smart. And I recognize this as something that I’m reluctant to commit to, like, “look at this smart thing that I came up with.” So I guess empathy may be something that we all share subconsciously and not necessarily intellectually; response to one’s environment is also in that realm.

I’m most familiar with the work of yours that I saw over the last 6 years – I guess – through Hamiltonian Gallery, and it struck me that those drawings were very sensitive. And very much about light and shadow and formal in their way. And like you were saying, fairly intellectual and conceptual. But… I didn’t feel like I knew much about you from that work.

So, I think that this idea that you’re talking about – allowing things to be both smart and personal – it’s apparent here in these photos.

Since I graduated [from MICA’s MFAST program] and became a college professor, my work has became increasingly conceptual, and it seemed to be getting a bit dry. For this body of work, to come back to a personal subject was about maturing and acknowledging that I could make work that simply looks good and that could be the starting point.

Over the years, I rejected many ideas because I would start thinking about a project and immediately dismiss it as “too pretty”, not allowing myself to do it because it was not intellectual enough… And that was a dangerous place. I had to make a pact with myself to embrace every idea that came to my mind, just so I could be home and working, which I did – and I made three bodies of work. Not necessarily complete – but at least I started something that was interesting to me, and new, that would allow me to grow.

But there are certain photographs in this series that seem to show us a style of what you have in your home… very specific details, like lace curtains… Those are the only images that I might possibly draw a gendered conclusion from. I mostly just thought to myself,”who has those curtains?”

Europeans do. [laughs]

Right [laughs]. Perfect… exactly, yeah. So that can be kind of a cross-circuit in a way… they also look old… I don’t know if they are, or that’s just a look I associate with an antique, but I think that might connect to another sensibility also. Because it’s not like your house is necessarily… from what I can see… is not full of that sort of contemporary look that is easily purchased and replaced all the time. That having old lace curtains talks about time and tradition…

EV: It does.

It reminds me of the “Classic American Immigrant Story” – the preintegration, post-Depression period in the United States during the early part of the 20th Century… where keeping things isn’t just holding on to tradition and history and where you’re from – but across the board several generations were simply afraid to throw anything away because they were just afraid to lose everything because the economy is going to unexpectedly collapse. Which makes sense today…

It’s really interesting that you brought it up. Someone once said to me back when I was doing seascape work, that all immigrant artists, at least once in their career, do work about the sea. Back then, it seemed like complete bullshit, but looking back, I hold on to old things from Ukraine, perhaps to remind me of home that no longer exists; like old curtains that I grew up with. It’s really strange – they have holes and spots… and my children are probably going to throw them away. And that will be okay.

But I think you are opening a really interesting door here about how much one’s decision making is really affected by childhood and memories; and whether you want to admit it or not, or embrace it and “wave your immigrant flag”… perhaps it speaks louder in some cases.

It comes down to the objects you keep, that you collect… I think the lace is the one thing I latched onto because it was the one thing among the images that was very specific, and it is specifically repeated in series.

Many of the images are about blurring the specificity of space and details. Yet, the spaces in the photos feel very much like home. It feels personal without appearing specifically symbolic. Do people know these are images of your house? Could you do a series like this in someone else’s home?

I think I could do this kind of work in multiple houses. Honestly, I don’t think it matters. I hope the viewers can relate to the history of “a house” and the experience of a place.

What kind of “photography” is this? How did you make these – what were the objects I saw the show? Did you shoot on film? Digitally printed? There are so many combinations of ways to make photos and prints these days.

All images were digitally printed. The large photos were shot with large format film, scanned, and printed digitally. What’s interesting about working with large-format, is that you never see 100% of what you are shooting, the details are not fully visible on the ground glass.

It was great to see the nuances and little surprises that I didn’t intend to emphasize – little bits of paint chipping and certain interior details that you can see in the print, which I wasn’t aware of when shooting. The camera work was guided by thinking about the way we experience space: we cannot affix our eyes on something – our visual focus is constantly shifting; and in camera, out of focus things appear as a blur.

In the images, the blur means that something is really close to the lens, as if it is really close to someone’s face. I was curious to see the images of the spaces relating to one’s body; and printing them almost life size allows the viewers to relate to them on a physical level.

Are there reasons to present the smaller photos, rather than keep all the photos in the series at a similar scale?

The photos that worked well smaller could be displayed as a series, in a sequence, and somehow would compliment each other in a visual dialogue. The large images are displayed either as singles or diptychs and they didn’t need an army of other images to work. The smaller ones are more detailed, they have more going on and may relate more directly to the image right next to them. The larger ones are more independent.

The ultimate decision-making was really about how light transforms into pattern and texture. You encounter the light and have a macro/micro experience; as you read into the image and start paying attention to the texture of the wall, and the sense of scale translates as how big or small those textures are.

And you had more control over the images that you shot digitally, rather than large format… We think about photography as technology and it’s become ubiquitous as a very fast, momentary technology [snaps] in how everyone shoot images on their phone. So, I’m interested in the speed at which you arrived at your images and if you think immediacy reflects “reality?”

The camera is a tool just like a paintbrush is a tool. Depending on the camera and the lens you use, the “vision” changes. Some people even dismiss digital photography as “not real photography” because there are SO many ways to manipulate an image; but you could never NOT manipulate reality.

The moment you take a photo, you are manipulating reality with camera angle, lighting, whatever. Reality is just too vague; a photograph is always a statement.

We should just admit that photographers take the image that came out of a camera and bring it closer to what they feel reality is; the idea that they are trying to communicate. We all do that; vision is so subjective.

I asked you the other night, if you felt like the experience of having made a body of photography for many years, and then done drawings for several years… and then now going back to photography… has that affected the way you make choices and the eye you have for details… have you had any further thoughts on that – can you answer that better today than you could then?

Between 2007 and 2010, I did a body of work titled Proofs, and photographed blank walls, re-introducing the images back into the original environments where the photos were taken. I was interested in the dialogue that happens between real space and the photographs. Over the years, it seemed like I was making the same work and the questions were not getting refined.

When started drawing, the questions became relevant again. In my current work, working with a large format camera is very interesting and somewhat unpredictable, and perhaps I can keep asking questions. Critique is very important, and thinking about your work is really important, and that is what the work is about, right? How you pursue it intellectually. But occasionally, there’s a point where you say, “I just don’t know, and I’m going to try this and find out as I do the work.” And then you may never find out.

The reason artists keep going is because we never need to find answers. It’s very easy to be critical of somebody else’s work and say, “the decisions that you’ve made are…” politically incorrect, or not feminist enough, or don’t have the sensibilities… but, ultimately we don’t ever stop making work because those questions transform into new questions, not because you answer them. Penumbra was an experiment.

*******

Penumbra is on view at Stevenson College’s Art Gallery, Greenspring Campus through October 6, 2016.

Author Ian MacLean Davis is a Baltimore-based artist and instructor.