Photographer Penelope Umbrico at MICA by Kerr Houston

Every artist, Kandinsky once proclaimed, has something in him which calls for expression. For Penelope Umbrico, who spoke about her work at MICA on March 1, that something seems to be an impish need to deconstruct superficially perfect bands of imagery: to lay bare the coarse and even embarrassing mundane realities that surround that highly curated home improvement website photograph, or that achingly perfect shot of two lovers on the beach, at sunset. And yet, if her work punctures certain ideal forms, it is also insistently affirmative, proposing a community that – for all of its kitschy, sloppy, repetitiveness – is irreducibly human. Much of her work, indeed, explores this basic tension.

Penelope Umbrico, 541,795 Suns (from Sunsets) from Flickr (Partial), 2006

Penelope Umbrico, 541,795 Suns (from Sunsets) from Flickr (Partial), 2006

If you know of Umbrico, you probably also know her Suns from Sunsets from Flickr, a project that first took shape in 2006. Discovering that ‘sunset’ was the most commonly used tag on the popular photo-sharing site, Umbrico downloaded a number of particularly clearly defined suns and sent the resulting images to consumer photo labs for developing, eventually exhibiting the resulting prints in gridded installations.

Seen in person, the result is both familiar and surprisingly rewarding. At first glance, the grids feel comfortably abstract, recalling early experiments in abstraction by Kandinsky and Klee. Step closer, though, and the piece becomes a meditation on a cliché: so many suns, shot at so many seemingly indelible moments, now reduced to a mere taxonomy. But stay with the piece a moment longer, and it also becomes a sly meditation on technology: light itself is converted into pixels and stored as a series of integers, and then finally rendered on paper, in a trite, conventional format. A subject that is fundamental and ubiquitous is thus pushed until it seems on the verge of overuse, or even exhaustion.

In the years since, as the number of sunsets on Flickr has only multiplied – 541,000 images have given way to more than 30 million – Umbrico has regularly returned to the subject, producing a series of increasingly ambitious installations and time-based works. But she has also turned to other subjects. Struck by the improbably pristine aesthetic of an armoire on a home improvement site, for instance, she began to collect photographs of used examples of the same armoire for sale on eBay and Craigslist.

Detail from Beautiful Armoire – Perfect Condition, 2009

Detail from Beautiful Armoire – Perfect Condition, 2009

Predictably, the actual, used examples were often swamped in kitschy clutter. Looking at the resulting series of images (which Umbrico organized in order of increasing entropy) is thus rather like watching the corruption of a Platonic ideal: a perfect form choked by the random demands of everyday life. But in working with such untidy images, the artist also found herself struck by the sheer guilelessness, or candid humanness, of the sellers who had posted them. “If you really wanted to sell your armoire,” she explained to her listeners at MICA, “you would probably not show it in this condition. And so I had this idea that posting images of objects for sale online was really a way of subconsciously connecting with other people.”

This subconscious, or oblique, aspect clearly matters to Umbrico. Indeed, she took time during her presentation to differentiate her favorite images from the nascent genre of reflectoporn, in which sellers purposefully include reflections of their own nude forms in posted listings. Rather, Umbrico seems most affected by the unplotted or inadvertent trace: the ghastly image of a beer belly reflected in a television screen, or the face of a dog staring up at the indifferent photographer intent on documenting the CRT television that she plans on listing for twenty bucks. In the apparent rush to post, such details are frequently overlooked, or simply ignored – until they are then excavated by Umbrico.

In a sense, she is thus something like the art historian who studies comparably subtle motifs in Old Master paintings. I’m thinking of Caravaggio’s Bacchus, whose glass carafe throws back a tiny image of the painter himself, and van Eyck’s celebrated portrait of the Arnolfini, in which a mirror in the background seems to record, in microscopic detail, our own presence. But such analogies are in the end only partial, for these painted precedents are the result of calculated intention and effort, rather than merely incidental, passive effects. Van Eyck, delighted by the potential of his oil paints, is willing to devote his energies to composing the mirror. A Craigslist seller, on the other hand, simply points and shoots – recording, it seems, without even looking closely.

Detail of van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

Detail of van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

Approached in this way, Umbrico’s work can read as an extended meditation on the medium of photography, and the evolution of photographic technologies. Since its invention, photography has been linked to the idea of absence: the photographed moment is fugitive, and the image (for all of its realism) only reminds us of what is now past. “What I like about photographs,” Karl Lagerfeld once said, “is that they capture a moment that’s gone forever.” Umbrico would seem to sympathize. Recently, she has collected images of remote controls and wrapped, used televisions for sale: objects that embody loss, and an almost abject quality.

But even as they are thus tied to loss, photographs can also be disarming in their richness of detail, suggesting an almost erotic availability. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes famously imagined a dense exchange of touches between subject, photograph, and viewer: the indexicality of the image is seen as potent, and arousing. Umbrico’s work evokes broadly comparable sensations, albeit with slight differences in emphasis: for her, it is ultimately the immediacy of the unedited immediacy of much online photography that affects.

“I’m traveling around America on Craigslist,” she explained, “and I’m being invited into their bedrooms, and I get to see all their stuff. These sweet, and intimate, and weird things, that we all have – but somebody’s opening their house to you.” Put like that, photography feels almost transparent, allowing access to spaces and behaviors (and bodies) that are usually highly monitored.

In the end, however, perhaps one can only stand so much intimacy. Indeed, one of the most salient lessons of Umbrico’s practice centers on the sheer, crushing surfeit of photographs available online. The filmless digital camera has resulted, of course, in a profligate approach to image-making: when it costs nothing to record an image, and virtually nothing to store it, there is no practical need to edit. And so the images multiply, much like the tchotchkes on our armoires, yielding in the process yet another damning proof of our wasteful, cluttered tendencies and banal tastes.

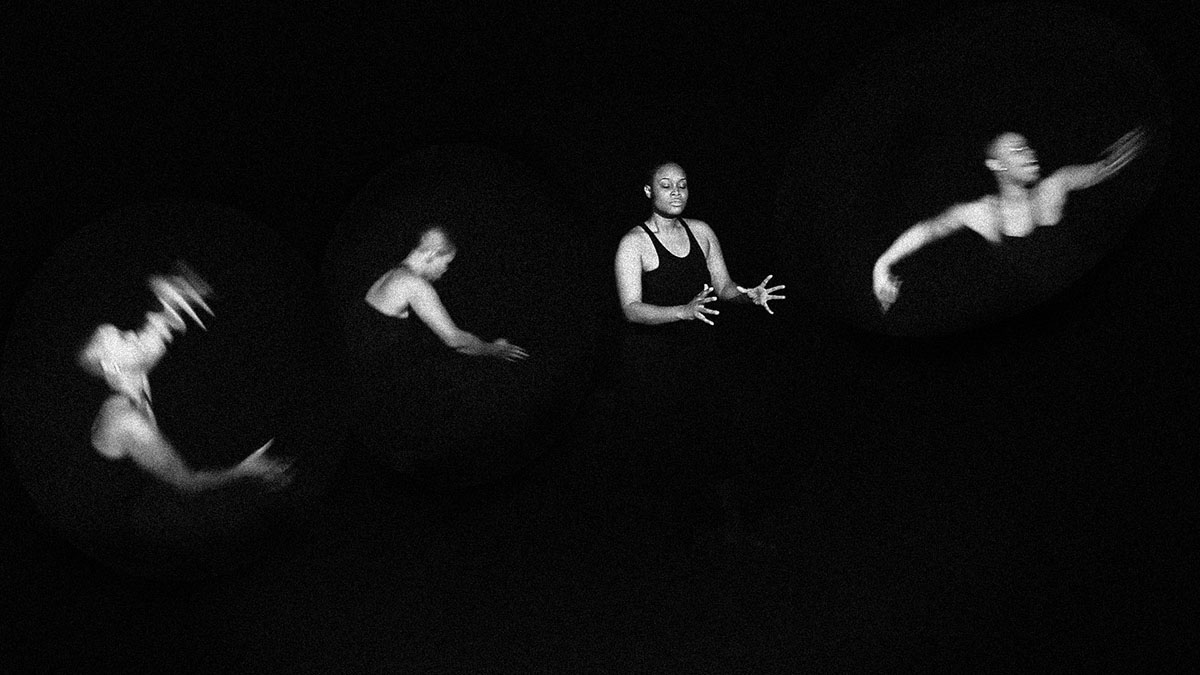

Excerpt from Pirouette for CRT, 2012

These various strands are deftly united in a piece like Pirouette for CRT, a 5-minute video consisting of still photographs of CRT televisions for sale. In juxtaposing images taken from slightly different angles, Umbrico manages to suggest that we’re moving around a single object, even as we know that we are in fact looking at hundreds of objects, photographed in different circumstances and wildly disparate locations. Active editing, then, creates a sense of a fictive continuity – much as Christian Marclay did, in his sublime project The Clock. But it is in the end only a fiction, a product made possible by the simple sprawl of the Web: for, despite the effectiveness of the illusion, this is ultimately a pirouette formed of awkward, lurching transitions. Built out of clearly various parts, it implies a seamlessness even as it also forcefully reminds us of its constructedness.

We are all, Benedict Anderson once argued, members of an imagined community: we pledge allegiance to a nation that can never actually display or perceive itself, all at once. The sheer scale of any country, that is, inevitably effects its abstraction. And so too, perhaps, with digital photographs: as the billions of individual examples continue to proliferate, the perfect sunset becomes a trope, the unique moment is shown to be a cliché, and clean geometry is subsumed in a glut of stuff. We may be tempted to seek out, in such a flood of images, a sense of community, and Penelope Umbrico’s practice is largely founded upon the touching appeal of the offhandedly commonplace. But if there is thus a partial grace in the fact that we are irredeemably human, that grace is also fleeting. We may be invited in, as she likes to put it – but we are also reminded, again and again, of the abstraction of community, and of the resolute superficiality of a photograph. The surface tempts, in other words – but the reality beneath and beyond it is rather more complicated.

*******

Author Kerr Houston teaches art history and art criticism at MICA; he is also the author of An Introduction to Art Criticism (Pearson, 2013) and recent essays on Wafaa Bilal, Emily Jacir, and Candice Breitz.

Top Image: (detail) Penelope Umbrico, 541,795 Suns (from Sunsets) from Flickr (Partial), 2006