Interview with Curator Kimberly Graham by Alexandra Oehmke

For decades the late William Christenberry’s photographs of the Deep South have been championed by the art world. The photos show a romantic decay, a nostalgia for a childhood in a place Christenberry never fully understood. Trained as a painter, Christenberry continued this practice throughout his life while seamlessly tying in sculptures, installations, and his famous photographs that were originally taken only as references for his paintings.

In Lying-by Time currently on view in MICA’s Decker Gallery, curator Kimberly Graham explores the connections between all of Christenberry’s studio practices and what his work means in today’s art education system.

What was the impetuous for this Laying-by Time? From start to finish how long did it take to put together?

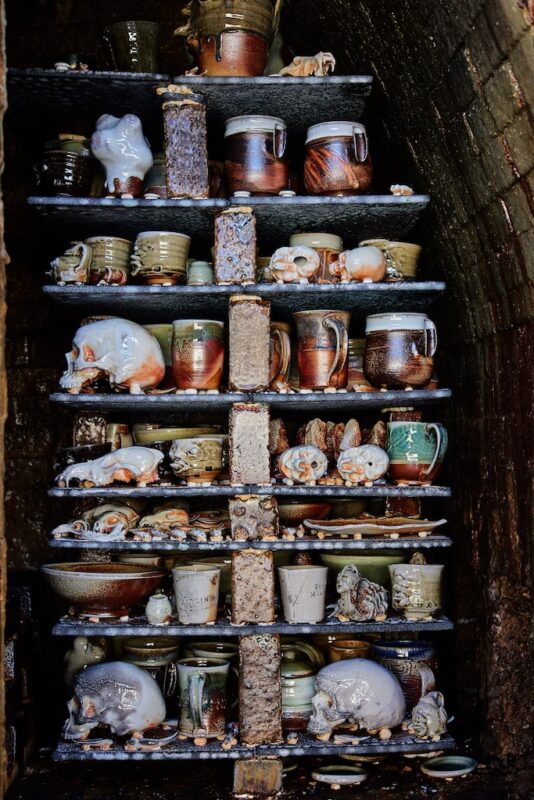

This exhibition really sprang from conversations with MICA’s Exhibition Department director, Gerald Ross, and our shared admiration for the artist, William Christenberry. We both recognized the rich and layered magnitude of the work and agreed that it would be an excellent opportunity for the MICA and Baltimore community to experience it, think about it, and respond to it. There is so much in the work to “chew on,” from his fluid movement across media – painting, sculpture, photography, drawing, found objects, story telling, and installation – and craftsmanship to the multiple veins of investigation – life and death, permanence and impermanence, good and evil – and their larger implications. So, it was truly a desire to share this work and give people in our community an opportunity to commune with work that I, personally, feel is rather fantastic.

As for how long it took to pull together… The idea, the seed of interest was planted over three, maybe even four, years ago but the earnest work took place between initial conversations with the artist’s studio in 2013 and a proposal to the Exhibition Advisory Committee in 2014 until the exhibition opened in December of 2016. So, 2 1/2 – 3 years.

You knew Christenberry personally, how did you meet him? Did your relationship to him impact curatorial choices you made for the exhibition?

I met him and worked with him during my days at Hemphill Fine Arts, the primary gallery representative of his work along with Pace/MacGill in New York and Galerie Thomas Zander in Cologne, Germany. Being in Washington, DC where the artist lived and worked afforded an enviable working proximity to his studio and artwork. I feel very fortunate and privileged to have had that experience. He was a mannered and gracious man.

As a curator it is important to strive for a balance between being professionally objective, an effective translator, and an experience maker. My goal is to shape an exhibition that ultimately allows the artwork to tell its own best story. Without the artist involved in the decision making it does fall to the curator to make knowledgable choices and I spent a lot of time thinking about Christenberry’s work, as well as what he imparted to me and others about his interests and motivations. I thought a great deal about what would both please him in the presentation and interpretation of his work, as well as what I thought hadn’t been articulated in an exhibition of his work before.

Undoubtedly, my choices were made with him in mind and I felt, because of my good fortune to have known and worked with him, that I was making informed and insightful choices. In fact, there are a number of subtle choices in the exhibition that are hardly apparent but are there because of what I knew and appreciated about the artist and his practice.

Christenberry died a week before the opening, did that change the meaning of the exhibition for you?

I like to think of Christenberry’s passing and the timing of it as poetic punctuation. That seems to suit the artist and account for the eerie synchronicity and beautiful sadness. Christenberry’s death certainly made it more poignant and emotionally charged; and the national and international announcements of his death brought additional awareness and attention to the exhibition.

People seeking an opportunity to experience his work are able to find that at MICA. When a musician dies, which we had a great deal of in 2016, all you have to do is turn on the radio or stream their music on Pandora, but to be able to commune with the craftsmanship, textures, and nuances of visual art, nothing compares to being in its presence. A Google search isn’t as satisfactory. I am glad the Laying-by Time exhibition is available for people to have that intimacy with and immersion in his work.

Can you speak a bit about the Klan room? Why did you choose to put it in the exhibition? How did you consider Baltimore as a city when making your decision?

Doing an exhibition that crossed the broad spectrum of Christenberry’s work was always the plan and in doing so one must include elements of the Klan Room Tableau. The installation constitutes a significant part of his creative effort and is an important part of the whole story his work tells. His work is an epic story that reveals a particular place, shaped by a particular history. It is about the tension of dualities, including good and evil. To not include the Klan Room Tableau in an exhibition such as Laying-by Time would be to tell an incomplete story, even to “white wash” the history embedded in his work.

Showing the installation is always something that should be done with care and consideration, especially with the community and audience in mind. Our conversations about the exhibition and the inclusion of the Klan Room Tableau were always mindful of the potential discomfort and reactions it might elicit. Maryland is the northern most southern state and there is a deep and complicated history here associated with slavery, abolition, the Civil War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Klan.

That it would be so relevant and timely as a result of the Baltimore Uprising and the contentious Presidential campaign and election that drew open support from white supremacist organizations was not something we had anyway of knowing would happen. It seems so important now to be reminded of this history and confronted with the consequences of the sickness of hate and demonization of others.

Christenberry taught at the Corcoran for a long time, what does it mean to display his work at MICA, another academic art institution?

Showing Christenberry’s artwork in any academic environment invites an intellectual contemplation and engagement of his content. The nature of the environment offers an opportunity to facilitate that investigation through a variety of channels. Showing it at an art school invites another level of investigation: one that particularly wants to understand not only the content but the process — the how and why of it being made.

As soon as Christenberry finished graduate school he started teaching. He taught at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa (his alma mater), the University of Memphis in Tennessee, and at the Corcoran where he taught from 1968 until he retired. He was the kind of teacher that didn’t tell his students what to do or how to think. Instead, he led them to the important questions and encouraged them to come up with their own investigations and resolutions — much like his work.

I hope showing this work at MICA means that lots of people are looking at his work, studying it and thinking about it, appreciating the craftsmanship, pondering the historical, literary, and artistic influences, as well as recognizing the breaks from tradition. I hope that viewers are considering what it takes to develop a unique creative voice and to construct a body of work with such comprehensive vision. I hope that viewers recognize that Christenberry was always an artist, first and foremost, but that he chose to look, see, and share what other people in his position might have looked away from. Having the exhibition at MICA doesn’t in any way mean that it is just for artists and students of art, but it does emphasize the process and practice – which is equally pertinent to the appreciation of Christenberry’s work.

Color is important to Christenberry’s work and this exhibition. What were you thinking about when picking the wall colors?

Christenberry was a colorist. His photographs gained attention because they were color and the color was integral to the image. When he took those initial photographs, he was thinking of them as tools, as a method of capturing a place — its architectural elements, its textures, its colors – so he could recreate that in his paintings. His images are landscapes punctuated by human constructions and their lives. The colors in the exhibition are the constants of his photographs – sky and earth — particularly, the red clay soil and the morning and evening sky.

I was definitely thinking about the earth and sky of Christenberry’s works. The importance of place but also the way his work transcends place. No matter who we are or where we are, we recognize the colors of earth and sky because we share them, day and night.

Laying-by Time has had programming around it, including a curatorial practice class you taught. Can you speak a bit about some of the programs and your class?

A true advantage of hosting an exhibition such as Laying-by Time in an academic environment is the emphasis on programming and integration into the curricular fabric.

When thinking about programming possibilities, I wanted to have an opportunity to give audience members a variety of access points and opportunities to learn about the artist and think about his work, especially with regard to how it is germane to our present.

The two panel discussions were conceived to bookend the exhibition. The first, Revisiting William Christenberry: Southern Narratives discussed the man, the artist, his unique practice, and inspirations. The upcoming second panel was constructed to discuss the significance of his work, its relevance, as well as the responsibilities – if there are any – of the artist to actively engage in political commentary and activism. Similar to the panel discussions is the Gallery Walk & Talk with Sandy Christenberry, the artist’s wife, who will share her memories and reflections of her husband’s career and their life together.

Film is much less didactic. Its like answering a question with a question or responding to an artwork with a poem. It seemed like a great way to connect with the exhibition and Christenberry’s work and expand the conversation at the same time. The films are very different from one another but are all connected together and with Laying-by Time through their exploration of “the evil in our midst.”

Just having the exhibition on campus is amazing because students, faculty, staff, and community visitors are constantly coming and going from the exhibition. I recently spoke to a student who told me about a course assignment that required students in the class to write a constructive criticism paper of the exhibition. That wasn’t a prescribed program that I sought and made to happen as curator. It is an engagement that the faculty member, Kerr Huston, took upon himself to incorporate into his course. Others such interactions are happening with the MFACA program through the efforts of Paula Phillips and with Shyla Rao’s Curatorial Literacy course that not only engage the graduates of the Masters of Arts in Teaching but the community group DewMore Baltimore.

Last semester, Fall 2016, I taught a Topics in Curatorial Practice course that focused specifically on the curatorial challenges, opportunities, and responsibilities associated with solo exhibitions. We used the then upcoming Laying-by Time exhibition as a real time case study and students had to learn about the artist, think about the context of his works’ creation and reception, and work together in teams to propose their own Christenberry focused exhibitions. It was a truly challenging and rewarding class.

The programming is such an important way to draw audience to the exhibition, and expand understanding through information sharing and dialogue. It is how an exhibition fully comes to life. I am incredibly grateful to MICA and the MD Humanities Council for making a great schedule of events come together.

*********

Author Alex Oehmke is a MICA Senior and BmoreArt Intern.

Laying-By Time at MICA’s Decker Gallery will be up through March 12, 2017.