A Studio Visit with Painter, Musician, and DJ Landis Expandis by Maya Alexandri

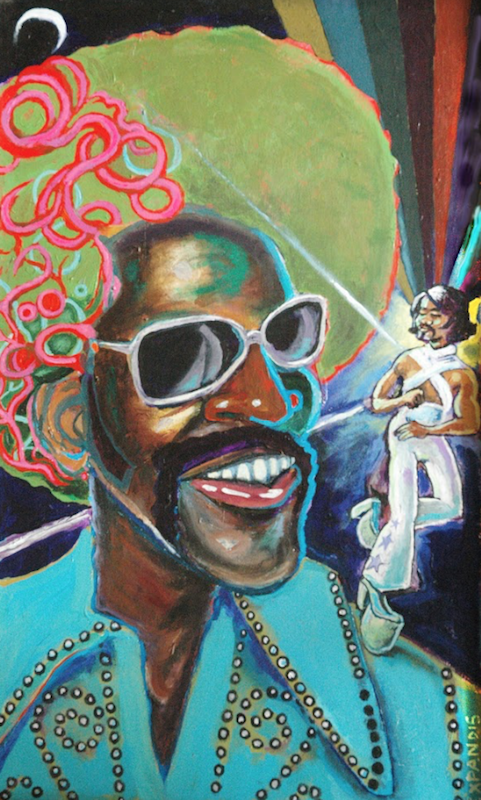

Landis Expandis is a man of multi-faceted talent: he is a painter, musician, and DJ. Best known as the lead singer and drummer for the All Mighty Senators, a Baltimore funk rock band that has toured the country and released more than fifteen albums, Landis first moved to Baltimore in the mid-1980’s to attend MICA.

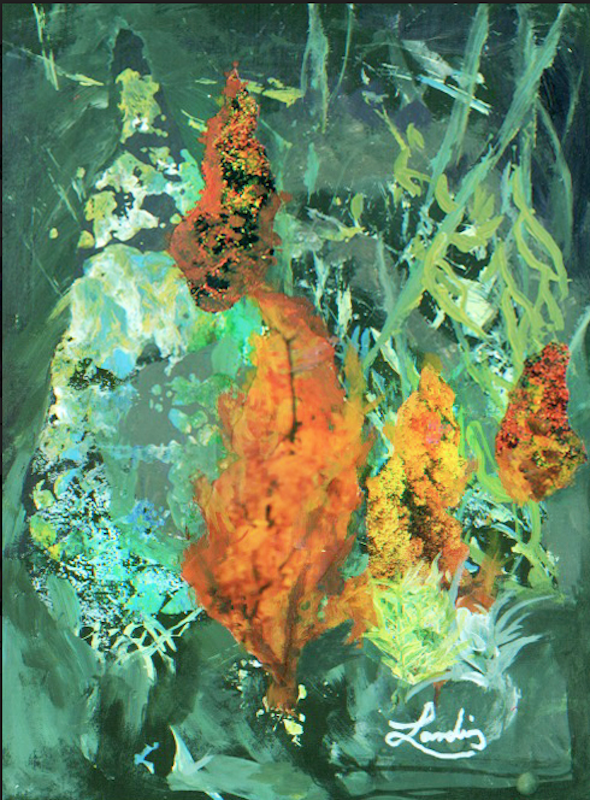

“I came to Baltimore to be a painter,” he says. In January, Landis began posting abstract works online that were a radical break with his earlier figurative work. I met with him in his studio in his home in the Arcadia neighborhood of Baltimore to talk about his shift from figurative to abstract painting.

How long had you been thinking about transitioning from figurative to abstract work?

Years. I think it was that movie about Jackson Pollock [from 2000]. There’s this point in the movie where the art crowd was saying, “The form is so gauche. Anyone can render the form if they take enough classes. That’s not necessarily art.”

The light bulb went off when I saw that movie because Jackson Pollock was looking for his thing, and it took him a while, but when he found it, he was like, “Yes! Movement and color and expression!” And I was like — that’s what I want.

It took me a long time to make paintings that weren’t literal. When I tried to do this before — and I have some earlier attempts — it turns into a tree-ish. A mountain-ish. And I didn’t want to make form at all. I wanted to make expression with no form. So I’ve been trying to make paintings that are just expression.

Why do you think it took so long to make paintings that are “just expression”?

Every time I put my paintbrush in my hand, my hand starts to do the thing it’s always done. Like, is it a face? Is it a tree?

Do you feel like you have muscle memory in your hand?

Yes. It’s the same thing when I play drums. I start playing the same beat I’ve always played unless I try to get away from that.

I don’t even trust the paintbrush anymore. I disrespect my brushes and leave them in there. The brush is a straight line. It’s rigid. No matter what you do, you have to practice to be loose, like Van Gogh. You have to been loose in your wrist. Even when you do that, it’s still you practicing [being loose].

I take gobbled up string to make these lines. I take it, I fray it, I mess with it, and I dip it in the paint, and a lot of times it will figure out where it wants to go, and I’ll say, “Yeah.” It’s like I’m having a conversation with the uncontrollable. My hand is in it. But there’s something uncontrollable about the lines that are happening.

Another thing I do is I paint plastic. I’ll press it down and part of it will stick and part of it won’t and I’ll peel it up and see what I’ve got, and I’ll put another color on top of that. I also work with my fingers a lot.

Other than Jackson Pollock, were there other painters who were influential in your transition from figurative to abstract?

Klimt. I can’t even look at Klimt because his paintings are so good that it makes me want to stop [painting]. When I was doing figurative paintings, his paintings are so close to what I wanted to say, and he’s doing it perfectly. I might cry a little bit if I saw one of his paintings in person.

When I was trying to make abstract, I would look at Klimt and see how his figures are coming out of abstract shapes, and I’m like, “How do you come up with those shapes and designs? What is that based off of? Is it based off of draping cloth, but instead of making cloth, you just put the design out in the sphere? Where is that coming from?” It seems to just flow, too. So perfect! He’s the pinnacle of everything. It’s too good.

Was there a “breakthrough” painting that allowed you to make paintings that were not literal?

Yes. Three Muses. I drew this form [of the dancers] several times. I actually cut [the dancers] out, and I had this little cut out, and I would hold it, and I would take a picture of it in front of trees. It got to a point to where the importance of this form was the negative space it was making. And nothing else. The only reason for this form is the negative space.

And then the trees: I was getting into the fact that this almost doesn’t look like a tree. And I thought, the next painting I’m not going to have the dancers in it at all. I’m just going to paint based on nature, and I’m just going to go off on color and line and figure out different ways to put this expression on there without fooling with people. This is a good painting, but it’s not necessary to say, Three muses were once dancing in a garden, do you get it?

What’s the expression in this painting?

This was an actual day, you know. The sun was right about there. It felt good. The trees were poppin’, doing their thing.

A dimension of collage was important for Three Muses. Collage looks to be of continuing importance in your abstract work, is that right?

Yes — I can have a failed painting, and then I start the collage and make it a success. It’s another way of — it’s another vehicle. I need more than one vehicle. I get lost. I get lost in color. I never get lost in composition…yeah, I do. If I use two different languages in my sentence, it helps me finish it faster. I don’t know why it works. But I discovered it, and it’s working.

So, in your abstract work, does negative space continue to be important?

Yes – that’s how we define everything, isn’t it? There’s this, because this isn’t that. There’s dark because it’s the absence of light. Negative space is one of the “bases” that’s got to be covered before a painting is done. There has to be parts that aren’t, and parts that are.

What are the other bases?

Everything needs to draw the eye — I’m a composition nut, so if there’s just something in the middle of the paper, I hate that. But if your eye goes here and then here and then back to there, and it’s a pattern, that’s it.

So negative space, movement — drawing the eye — and composition are important. Is there a color range that you feel like the painting is going to need?

I do struggle with color. I’m not going to lie. I’ve put colors together that just shouldn’t go together. I don’t really know sometimes what I’m doing. I like things that are ugly, but I know not a lot of people do. Ugly things are interesting. They’re the passed over.

Why do you work with the cardboard on a flat surface?

I’ve never asked myself that question. Let me ask myself that first. If it’s on an easel, it’s got to be one those iron easels they have at MICA. Because I push on stuff. I don’t want anything to give when I’m doing that. I need a solid surface. And I need to be on top of it.

That’s like when you’re sound-mixing as a DJ.

Or when I’m drumming. I’m on top of it, and putting my hand into it. An easel is like this long line here, rigid, it’s like I’m trying to get away from that, and the easel is just making me stay there.

Let’s talk about the recent Diebenkorn / Matisse exhibit at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Diebenkorn made a move from abstract to figurative, and then back to abstract. How did that exhibit strike you, given your own transition from figurative to abstract?

It was interesting. Diebenkorn didn’t grab me as much as Matisse, but it was interesting to see someone who loved Matisse the way I do. And when I saw it, I was making my transformation into abstract, so I understand. I was just pretty much jiving with what Diebenkorn was going through. He had his Matisse books there — I’ve got mine here.

Sounds like you’re feeling Diebenkorn. So what does it feel like? Is it like a yearning?

All of painting is a yearning. It’s just a non-stop yearning that you have to answer. Doesn’t matter where you’re going with that. You’re moving from place to place to try to answer that call. The whole thing is a yearning.

Diebenkorn made his shifts from abstract to figurative and back roughly in his midlife. Do you see a connection for yourself between the shift from figurative to abstract and midlife?

I don’t believe in mid-life. I think this whole life is just an embryo stage.

Do you feel like there’s a compulsion to paint?

I have ancestors who are very creative, and they chose not to respond to it. But when they were coming up, if you were artistic, it was like, “Ok you do that on your own time, we’ve got work to do.” There was no room for art — everybody had work to do. Black people had to hold themselves together, make sure they didn’t get lynched. Move their family northward. They had things to do.

Do you think that being artistic or creative for your ancestors was putting them at risk for being lynched?

There was just work to do. Everybody had a farm. There was housework. My family is from the South. My dad is very creative. But he would show it in ways that were acceptable. He would work on his garden: build these huge tee-pees with string beans that grew on the outside; make botanical sculptures – huge rose walls.

Let’s talk about narratives in art. You’ve just been mentioning narratives that may have prevented your ancestors from responding to their creative talent. You found other narratives. Your figurative work, for example, is narrative-based.

My figurative work includes portraits. A portrait is personal. A lot of my earlier paintings have black people in them and a lot of the audience that came to see them was white. I purposefully did that because you seldom see paintings with black people in them unless it’s a black show or a black art gallery. I wanted to just throw them up in places where you wouldn’t necessarily see them [like the Hon Bar].

And how do audience members respond?

If you’re used to seeing white faces on all your favorite shows, and it is a portrait, and you’re trying to take that in as part of yourself, and you only have one black friend, it doesn’t work. It doesn’t have anything to do with being racist. It’s just, I don’t know what that experience is.

There definitely was a narrative gap. I had my paintings in Art-o-Matic, and I just hung around to see what people stopped at. And it wasn’t my art. People stopped at things that were made out of something else. Oh look, it used to be a book, and he made it into this. That’s something people can grab onto. They go, I recognized that used to be something, and now it’s this. I get what they’re getting at: there’s something to grab onto. That’s their narrative.

Have you noticed a different kind of response to your abstract work?

More people get my abstract painting than my portraits. People make their own story when they look at this. Abstract is like moving beyond words. Words are very limiting.

***********

Maya Alexandri is the author of the novel The Celebration Husband and numerous short stories. She is based in Baltimore and is one of the collaborators behind the Amplified Cactus performance series.