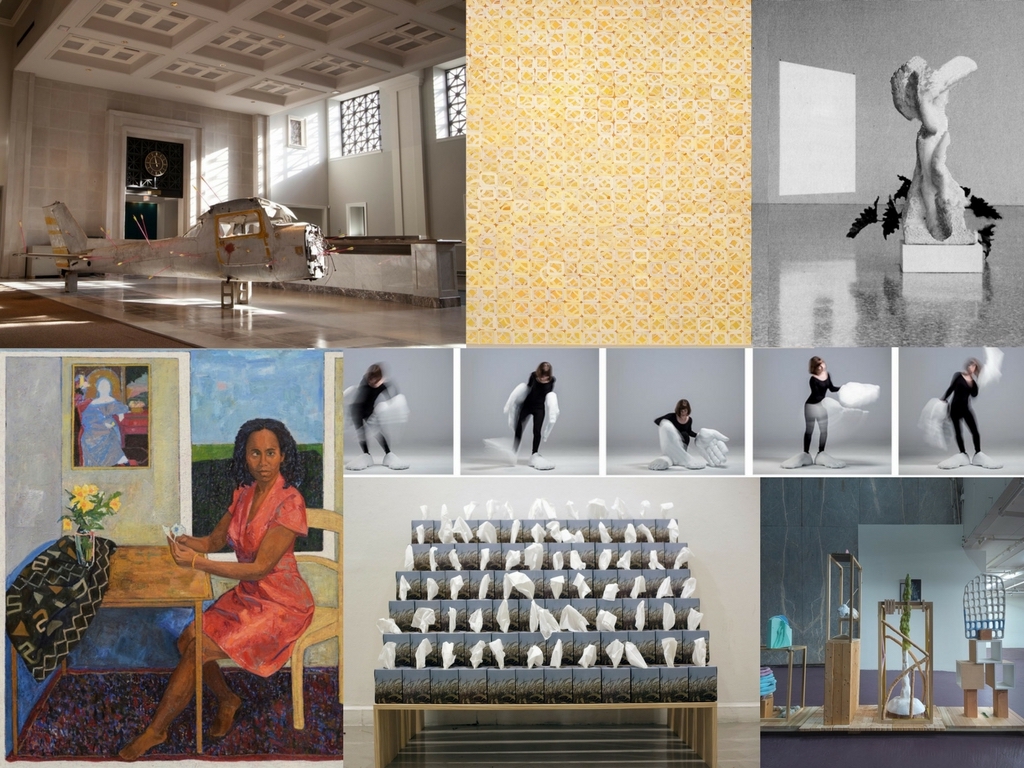

Wickerham & Lomax’s DUOX4Odell’s: An Interview by Aden Weisel with Photos by Joseph Hyde

When you enter the stage set by Wickerham & Lomax, the original club audio, music, and 1970s-inspired silhouettes make you feel like you should be rubbing shoulders with dancers, inhaling the smell of cigarettes, sweat, and booze.

This is the stage set at the former Everyman Theater by Wickerham & Lomax in their most recent exhibition DUOX4Odell’s: You’ll Know If You Belong. The exhibition is part of Light City’s attempt to reach outside the Inner Harbor in its second year and Wickerham & Lomax are the artists-in-residence for Station North’s contribution to Neighborhood Lights. The artist duo of Daniel Wickerham and Malcolm Lomax and Kimi Hanauer, Program Director for the Station North Arts and Entertainment District (SNAED), recently joined me to discuss DUOX4Odell’s. [Excerpts of that interview are included here and have been edited for length and clarity.]

Odell’s was a North Avenue club that operated from 1976 to 1992 and served as an exclusive and creative scene for the city’s African American community. The faux-Tudor building that once housed Odell’s has been shuttered since 1992 due to mismanagement after the death of the original owner, Odell Brock, in 1985 and pressures from gentrification. The building was recently purchased though and rumored plans to turn the space into retail units make Wickerham & Lomax’s attention timely.

Amelia Rambissoon, Director of Development & Operations for SNAED introduced the artists to the space. Hanauer said that the push from their organization stemmed from “Odell’s recent purchase and other changes in the feeling of this area and Baltimore in general. We wanted to bring an emphasis to the things that were happening here [before the area was known as Station North], setting the grounds for what is now happening.”

Wickerham & Lomax initially had plans to create a 3D scan of the interior of Odell’s. Their work often includes websites, digitally collaged images, videos involving CGI animation and homemade “props.” But when the artists accessed Odell’s, they found “an abandoned box.”

ML: It’s gutted out—nothing in there. I was hoping there was stuff there. We had a lot of expectations going in of what we thought the space should have been. When those expectations were gone…

DW: …it shifted the project.

ML: It shifted the way we had been working. There was a feeling that you wanted to hold—to let other people know the importance of something that felt funerary or gone.

The artists looked to research to inform their project, but “A similar thing happened online. We got to a point where we couldn’t find any more information. We reached a threshold and it was the same expectation that we had going into the space that there would be more.”

“There was a feeling that you wanted to hold—to let other people know the importance of something that felt funerary or gone.”

When they “didn’t have enough narratives to lead the project,” Wickerham & Lomax shifted their attention to the themes that they have worked with in their past few projects, themes that echoed in the history of Odell’s: loss, marginality, exclusivity and socialization, particularly club culture.

DW: Malcolm often says that Baltimore is like a material that we use. Part of this Drinkery project [Take Karaoke: A Proposition for Performance Art (2015) featured the Mount Vernon gay bar, which has been threatened by gentrification and the noise and violence complaints to law enforcement that also plagued Odell’s in its later years] was being deadly serious about how people hang out. There was a focus on what people spend their time doing when they go out. I don’t know if the two shows are linked exactly, but there is a prioritizing of something that seems frivolous but is not.

Odell’s past introduced two more elements into Wickerham & Lomax’s practice: documentary and collaboration. One of three videos in DUOX4Odell’s—collectively known as “Wormholes”—includes interviews with Odell’s DJ Wayne Davis and regulars Franklin Alexander, Chuckie Dennis and Kevin Mitchell.

DUOX4Odell’s “is not Odell’s as it was, but the mythology of Odell’s as it exists, right now.”

The latter three fall into the double minority of black and gay, providing the artists with a particular perspective on Odell’s history and its “built-in mythology.” Wickerham & Lomax have grasped this last idea and run off with it. As Hanauer points out, DUOX4Odell’s “is not Odell’s as it was, but the mythology of Odell’s as it exists, right now.” The artistic collaborations in this show help with that departure from history and documentary.

ML: The collaboration came about because of the nature of the project. In thinking about a club, community seemed important to introduce into this. Choosing a variety of performers, poets and musicians to be a part of the project was important for us, even though we, as collaborators, could’ve built something the way that we perceive it. But there’s something that happens when you’ve worked together long enough [Wickerham & Lomax have been working together since 2009, originally under the name DUOX.] that your voice becomes singular. In a way, this makes the voice more plural. It feeds off of other people.

Among the collaborative elements of DUOX4Odell’s are photographs of Keenon Brice, photographs and video of Elon Battle, video of Blairè Leòn and Kentrell Searles, and video of Janea Kelly performing her poetry.

Brice and Battle are particularly noticeable in the silver face paint and silver, knee-high, platform boots that they share in DUOX4Odell’s. Prior to installation, Brice could be found on promotional coasters provided to Station North and Mount Vernon bars. In the exhibition, his four images and a disco ball form a mobile in the corner.

DW: That’s something that we do often, where we keep the promotion in the show. That has to do with a focus on the ephemeral—something that gets a local or central context within the exhibition.

Battle’s image—repeated several times throughout DUOX4Odell’s—is larger-than-life in clothing reminiscent of the 70s. Lomax said that the alternative R&B musician and fixture at The Crown “lives like this. We didn’t just throw something on him—he dresses off-register. I don’t think it’s alien to people who are familiar with him—it just feels like reinterpretations of him.”

Wickerham countered that the clothing choices also had “something to do with us having distance from the experience of Odell’s. That wasn’t our experience and neither is trying to make clothes that reference the 70s, so that distance is innately built in. There was a foregrounding of those clichés of 70s outfits, because we never intended to do this amazing homage to the 70s. We decided to work with bell-bottoms and certain silhouettes that were well known. The clichés represented the distance from the oral histories that we couldn’t fully participate in.”

“There’s a legacy to Odell’s that people find important. It has a place of meaning for people and [ ] giving space for that. So it doesn’t matter if there’s a space between what it really was and the feeling that it has for people today.”

Those silhouettes are echoed in the transparencies of disco dancers that are cut into each image of Battle, casting elongated shadows of themselves on the walls of the old black box theater. The figures are etched with four poems written by Lomax.

ML: We thought it was just going to be the cutouts but then we put the poems in and we liked this because literal reading slows down visual reading—you have to renegotiate the thing in front of you. [Compared to past works, Wickerham & Lomax] needed these images not to be so graphically forward with people over-looking them just because of how fast they could read them visually. They’re more objects than they are images.

The poems themselves are sometimes narrated from the perspective of Odell’s physical structure. They speak of aging and the loss that comes with time.

ML: I was weaving between the actuality of the building now and assumptions about its life during occupancy. I’m making up a lot but with tidbits of information from research and interviews rather than just my imagination. I’m starting to pull little bits of things together to write these. I’m saying, “The hope for the space that could’ve been is gone. Knowing that this hope is gone, what do you do after this?”

ML: I think about expectations, because the reality of those expectations is gone. We’ve had so many people say, “We used to go to Odell’s every night!” What is happening to the people? Are they being displaced? Are they being moved? What happens when these stories are constantly told to their kids or the next generation? Are they thinking, “No space I go to lives up to the stories of Odell’s that I used to hear?”

While Lomax’s poems or anything in DUO4Odell’s may be reduced to historical fiction, the work plays a significant role in the practice of Wickerham & Lomax, the memories of those who knew Odell’s in its heyday, and as a guide for how to treat Baltimore’s people, histories and spaces.

ML: It doesn’t seem like we’re that interested in history to most people but we are interested in these forms that produce culture.

DW: I was reading this Oscar Wilde thing where he was saying something like, “You don’t know Japanese people because you’ve seen a Japanese painting. You go and visit Japan and you see people who look like everybody else.” It was something about how you’re letting images of people coexist next to them, but they’re not so linked as you might imagine. They’re more autonomous than their representation.

It doesn’t seem like we’re that interested in history to most people but we are interested in these forms that produce culture.

KH: From my perspective, this exhibition is linked closely to what Odell’s was and the history of Odell’s. This is how history lives for the people in those interviews and how that affected you, as people who are living in Baltimore and doing creative work. In that sense, the separation doesn’t matter. A memory is never going to be the exact thing that happened, but what’s important is that the people in the interviews shared something important with you. There’s a legacy to Odell’s that people find important. It has a place of meaning for people and you guys are giving space for that. So it doesn’t matter if there’s a space between what it really was and the feeling that it has for people today.

Towards the end of our interview, Wickerham & Lomax threw out a multitude of ideas that they’d like to pursue next. They keep a list of all possible projects.

DW: I find that weird things that we throw out as hopes and dreams for the practice—we’ll end up doing them. We sometimes take years to come around to it. At some point you just decide that it’s time to make these and then they come out at a fast speed because they’ve been incubating for a long time. The ‘to do’ list will get done.

One thing is clear though, DUOX4Odell’s bookends a trilogy investigating club culture that has run its course for Wickerham & Lomax. And the next time that you see them, it may be in a new art form.

ML: We want to continue to open ourselves up to forms, not to master them, but to experience them. Exploration is that space that artists thrive in. When people keep teaching you to professionalize, you lose that. We’re working towards this space of…

DW: …not being professional installation artists.

ML: We don’t want to be suffocated.

******

Wickerham & Lomax’s DOUX4Odell’s: You’ll Know If You Belong is on view Tuesdays – Thursdays in April, 12 – 6 PM at 1727 N. Charles Street. There will be a closing reception on Friday, April 28, 7 – 10 PM, which will include a catalogue release.

Aden Weisel is a Baltimore-based curator, art historian and writer.

Joseph Hyde is a Baltimore-based photographer. Check out his work as an photographer of art here: http://www.arttoimage.com.