Nicole Dyer and E. Saffronia Downing’s Regular Goods at Terrault by Ryan Syrell

Nicole Dyer and E. Saffronia Downing’s Regular Goods is framed as an exploration of the quotidian; a presentation of the mundane, overlook-able materials and things which coalesce around us as we maneuver through the world. Dyer and Downing offer up a landscape dense with these objects: phones, books, bananas, corn, blankets, doormats, cups, and other vessels.

The stated aim of the show—a cartography of the everyday—is certainly accomplished (perhaps more overtly by Dyer), but what makes the work of Regular Goods most intriguing is the way in which both artists situate bodies in and of the things of the world. In the worlds established by Downing and Dyer, recognizable human bodies tend not to dominate space; rather, they are embedded in space along with everything else, sometimes just hinted at or implied through objects.

In this manner of considering the world, we may just be things among countless others, or perhaps it would be better to consider every bit of material as embodied. In an earlier statement, Downing asks, “What if regular material is as much body as flesh itself?”

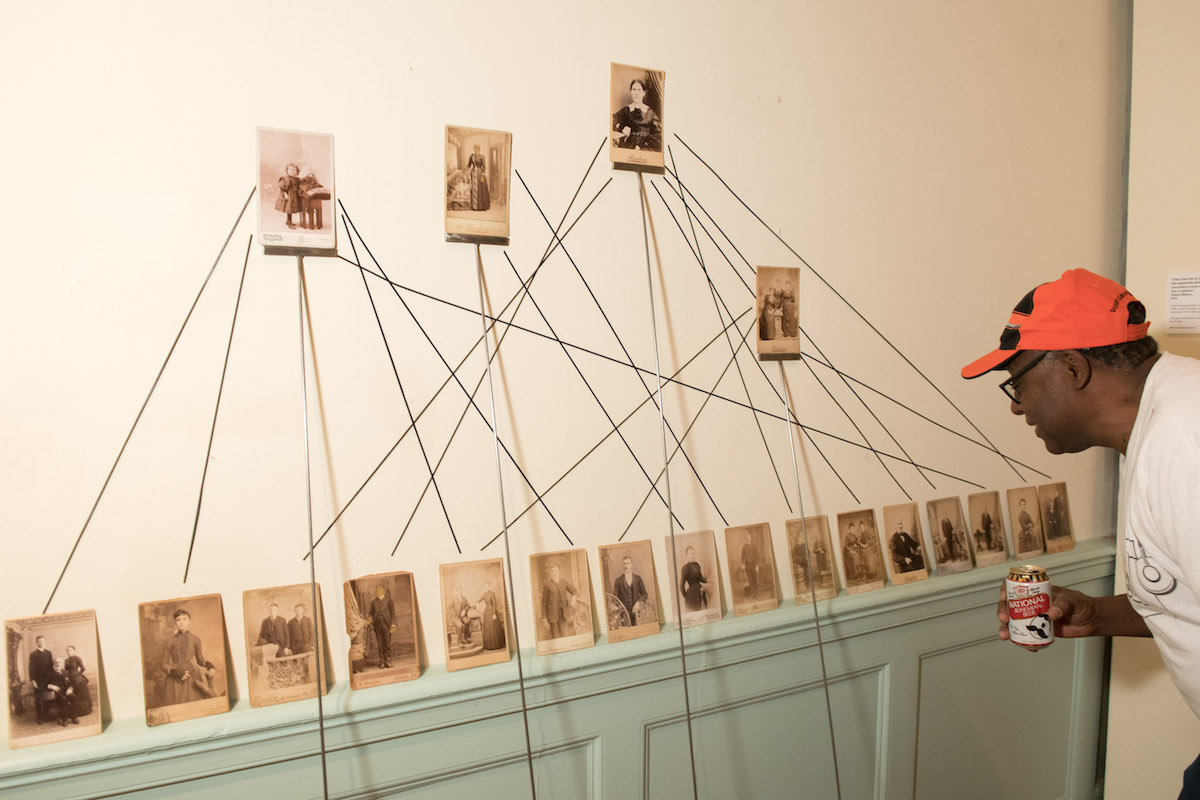

Detail of Downing’s “Untitled (strung)”

Detail of Downing’s “Untitled (strung)”

The primary means by which Downing and Dyer achieve this sense of body/thing/space interrelatedness are tactility and a sense of humor which always keeps sadness close at hand. Both artists operate with a wide repertoire of materials and handlings, as well as a playfulness which slips between subtle and slapstick.

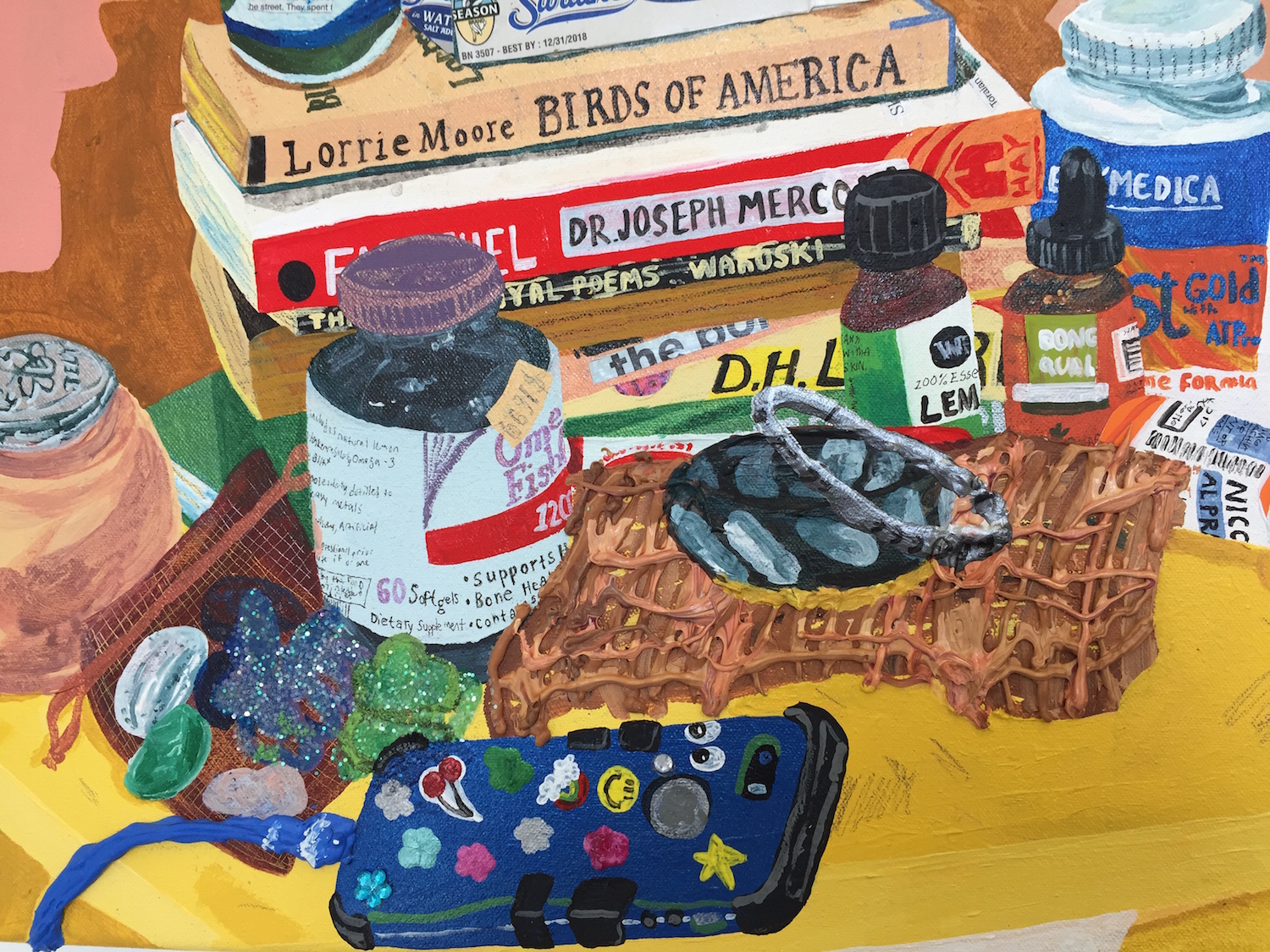

Dyer “Swipe”

Dyer “Swipe”

Downing’s work combines handmade clay objects (vase-like vessels, ears of corn, bananas) with store bought materials like pvc pipe, plastic sheeting, and poly-fill. These objects are animated to a surprising degree: dangling, drooping, suspended, and embedded throughout the gallery. Their presence oscillates between stoic and absurd. All of this together, the tactility, humor and sadness, stirs an empathy which can catch you off guard; it reaffirmed my read of them not just as metaphors for bodies, but as bodies in and of themselves.

Downing, “Half Sister 3”

Downing, “Half Sister 3”

Along these lines, Downing’s works relate to those of Hesse and Bourgeois (along with certain of Nancy Graves’ 1980s polychrome bronzes). A comparison with Hesse’s “Several” (1965) is unavoidable, but, deserves just a passing mention. One of Downing’s most captivating pieces in the show, “Pillow for Clarissa,” moves forward from these precedents. In it, two sewn pillow/pouches of different sizes and materials are suspended from the ceiling at different heights by means of a few pieces of pvc pipe.

It reads as material, body, individual, couple, and mirror. For all its’ material legibility, it remains oddly difficult to parse consistently. It recalls the writing style of Silvina Ocampo—a slippery syntax which forces you to re-read an ostensibly simple sentence numerous times, never allowing you to rest in the certainty that you’ve pinned down its’ absolute meaning. Again, it’s an odd mutability that contributes to the sense of these objects as an autonomous presence.

Downing, “Pillow for Clarissa”

Downing, “Pillow for Clarissa”

Dyer’s paintings keep us rooted more literally in the world, specifically in the intimate world of her sensations and experiences. In navigating them, I was reminded of Anni Albers’ Material as Metaphor: “Something speaks to us, a sound, a touch, a hardness or softness, it catches us and asks us to be formed.”

In a way, Dyer’s paintings can be experienced as precisely that: touches, sounds, hardnesses, softnesses. They are extremely engaging paintings, as both tactility and opticality either work alongside one another, or vie for predominance. Sounds, actions, and spoken or thought words regularly appear in the paintings, and are typically painted with greater painterly presence that “actual” objects.

Dyer, “Googling my Symptoms”

Dyer, “Googling my Symptoms”

One gets a sense of emotional and sensory superabundance from Dyer’s paintings. She consistently and eloquently uses one of the tools unique to painting; the ability to dilate a moment, to both amplify and simplify, to spend hours, weeks, or months inhabiting an incalculably short instant. This is what allows these paintings to become much more than straightforward documents

Another key to these paintings is their idiosyncratic take on precision. Dyer has a clear predilection for getting things “right” while still allowing for massive amounts of interpretation. The colors and typography on the paperback of “Daybook (in Bed-Stuy Bedroom)” are recognizable from across the room, but the cover photo of Truitt’s studio is instead a collaged photo of sliced bread.

Dyer, “Studio HH”

Dyer, “Studio HH”

The specificity that runs through Dyer’s paintings serves a purpose other than autobiographical documentary, helping to weave together the artist’s biography with those who view the work. In this way, Dyer has much in common with Georges Perec—in particular, with Perec’s “Je Me Souviens.” This book collects 479 of Perec’s own memories, with the stipulation that the memories not be exclusive, i.e. Perec recalls a personal awareness of these things, but they belong to the broader culture of his generation. In this way, the things which Perec remembers become synonymous with the memories of countless others; I see this as precisely the use of specificity in Dyer’s paintings.

Dyer’s strongest works typically present a moment of emotional intensity (which may or may not be overtly narrated) and a nearly claustrophobic array of surfaces. They are the surfaces of the things we touch, where we rest our bodies, of what we ingest, what we read; they are the things that we fold into ourselves, and they are the means by which we fold ourselves out into the space of the world.

Terrault Will Host a Closing Reception: Thursday, April 18th 7-10PM

Top Image: Nicole Dyer’s “Bedside Table”