Female Sexuality, Rage, and Power on Display: The Walters Art Museum and Amazon’s I Love Dick by Cara Ober

Walking into Art of Asia in the Walters Art Museum, I was weirdly reminded of I Love Dick, the Amazon television series based on the 1997 novel by Chris Kraus that merged memoir and fiction into a new kind of feminist art manifesto. In particular, I remembered a scene from episode 3, where Devon, an artist and handy-woman, hosts a performance rehearsal with a circle of friends in an art gallery. They are reading excerpts of Chris’s love letters to Dick aloud to one another and it becomes a chant.

“I want to be a female monster/ I was born into a world that presumes something grotesque, unspeakable, about female desire / and now all I want is to be undignified / to trash myself / I want to be a female monster / I want to have the kind of sex that makes breathing feel like fucking / I want to be a female monster…” – Quote from I Love Dick, Season 1, Episode 3

One of the other characters repeats the monster mantra and begins dancing wildly around the gallery. She inadvertently knocks over a small sculpture by Dick, a world famous sculptor of macho minimalist phallic objects based on aspects of Donald Judd, Carl Andre, and Robert Smithson, and when the gallery curator discovers the damage she fires Devon in a rage. Dick discovers the broken pieces later on, and we experience a moment of epiphany. He shrugs and reconfigures the pieces of concrete into a triangle on the podium. With a pencil he changes the date listed on the wall text to reflect an update and walks away.

Sure, the symbolism is obvious, but so is the name Dick for a character representing all the silent, unapproachable, genius white male artists of recent art history. That Dick is able to accept the destruction of his phallic work and to salvage the piece as a triangle, a symbol of female potency, is significant. Dick may never be able to become accessible to the women who hover around him, but he can get out of their way and make space for them. He can respect them as creators equal to his own genius and acknowledge his own inadequacy as an authority in the art world. His willingness to be a co-creator in this scene means everything.

Although she begins the series as a hot mess / failed experimental filmmaker and the wife of a narcissist intellectual, Chris is transformed into a consummate artist when she falls madly in love with Dick and embraces her truth; she is filled with anger, lust, ambition, and frustration at being a female artist in a man’s world. When she begins to use her desire as content for her work, (not unlike Carolee Schneeman, Hannah Wilke, or Chantal Ackerman) she writes hundreds of love letters to Dick. Once shared with the world, the letters take on a wild fervor, creating an inspired “female gaze.”

A year later, caught in the throes of the #metoo movement, the television show predicted a wave of radicalized women surging with creative and destructive potential. In a culture where female rage, sexuality, ambition, and aggression are not acceptable, this show presents what I thought was a revolutionary model for women.

However, a recent trip to The Walters Art Museum proved me wrong.

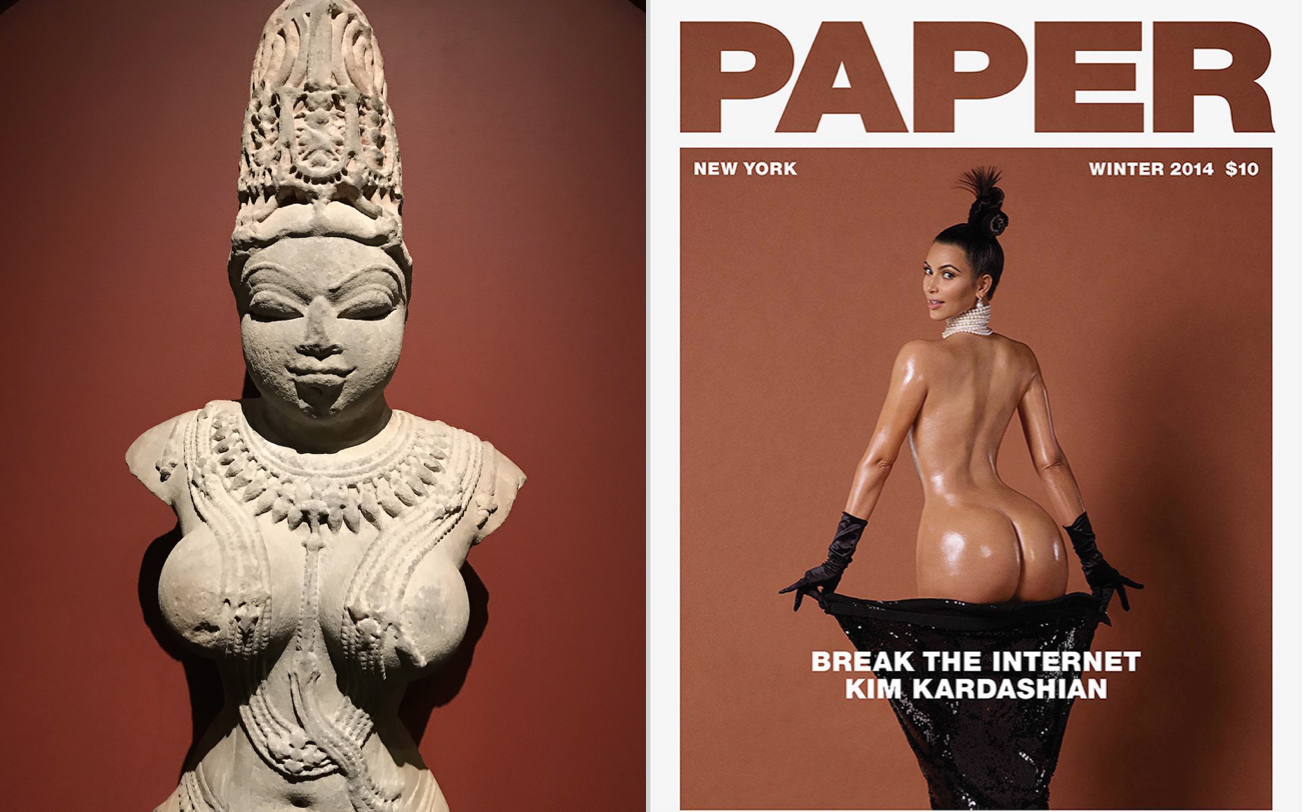

While viewing Art of Asia, it became clear that the archetype of the female creator-destructor is centuries old, as long as you’re looking closely and in the right places. While Western art history presents empowered, sexually liberated, and creative women as an anomaly, Eastern religions based in India, Nepal, and Tibet have long recognized the obvious dynamism of women as multi-faceted and contradictory goddesses and depicted them as such. Although there are plenty of male dieties represented in this show of sculpture, prints, books, and devotional objects, I was drawn immediately to several prominently placed images of Devi, the goddess whose force is believed to animate all living things and aspects of the natural and generative world—including destruction, reproduction, and copulation.

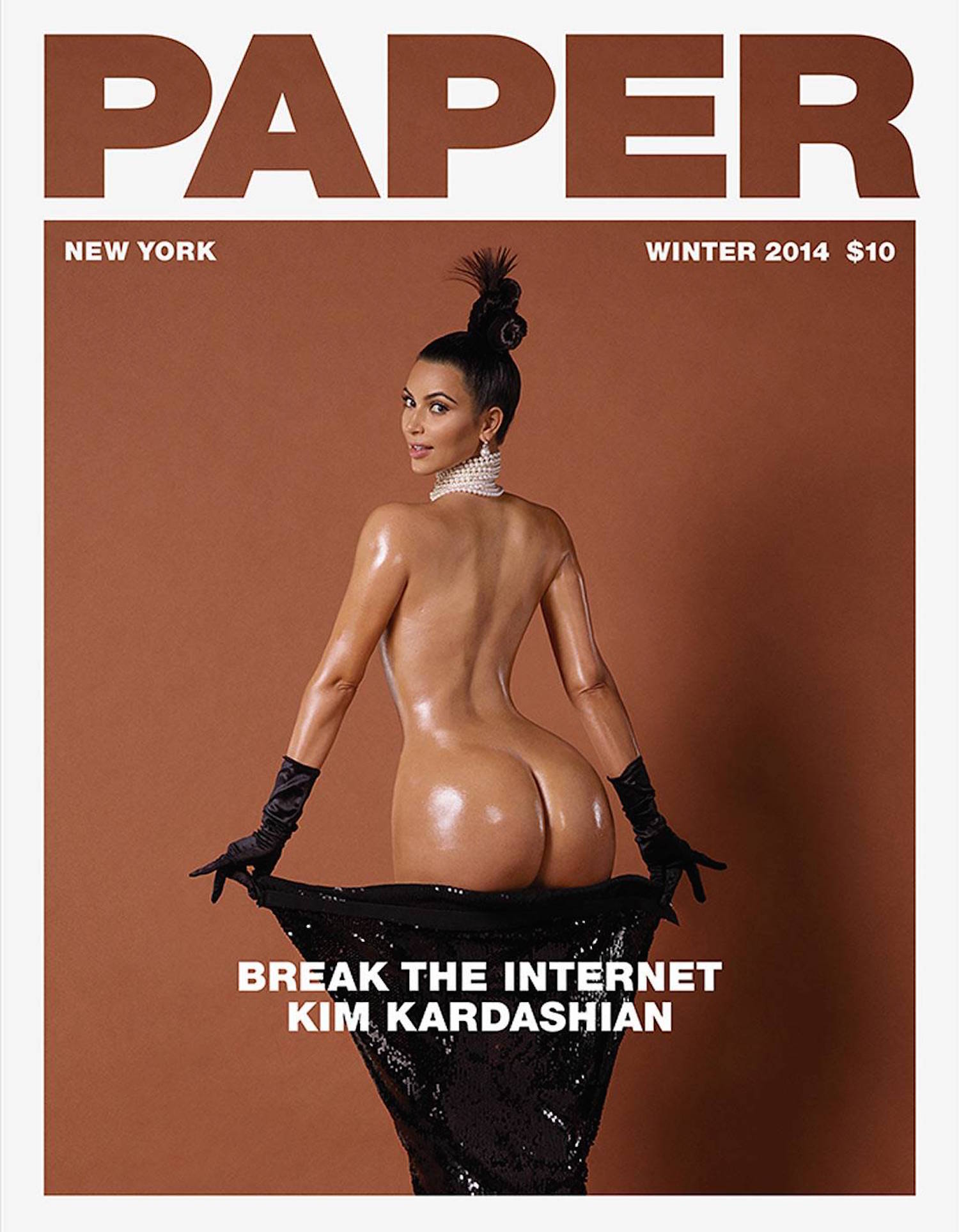

The first sculpture presented in the exhibit is a larger than life-size sandstone Devi, from India circa 975-1000. Her form is so curvy, I was immediately reminded of Kim Kardashian on the cover of Paper Magazine, where her very round and shiny posterior “broke the internet.”

Devi’s pose is frontal with wide and intelligent eyes, but her most prominent features are her grapefruit-sized, perfectly round breasts which float weightlessly above a tiny waist. This goddess has a body like a roller coaster. She was obviously designed to provide a certain reaction—accessible to both men and women, a pleasurable form of religious devotion that is stimulating, inspiring, and also healthily intimidating. This Devi is super sexy and she knows it. Like Kim K., she doesn’t give a damn what you think; she owns it.

What’s great about Devi, compared to archetypal images of Western women, is the way she cultivates your gaze and returns it without giving up an ounce of her power. No one is being shamed or exploited here. This female figure is beautiful and fearsome, a source of spiritual power where you, the viewer, are dominated. Devi inspires a fantastic, ecstatic experience because you are engaged in the act of worship, in awe of her. The Walters curators placed her front and center on a deep red background wall to accentuate her potential for passion. She does not disappoint.

“Woman Beneath a Mango Tree,” India (Rajasthan or Madhya Pradesh) ca. 850 in pink sandstone

“Woman Beneath a Mango Tree,” India (Rajasthan or Madhya Pradesh) ca. 850 in pink sandstone

Another jaw-dropping study in luscious curves is “Woman Beneath a Mango Tree” from India (Rajasthan or Madhya Pradesh) ca. 850 in pink sandstone. Placed high up so you can revere her as she was intended, at the top of a pillar, this relief sculpture is a cascade of undulating hips, breasts, and ripe mangoes. Like Devi, the mango goddess shows through her languid pose that she is not concerned with you. She is comfortable in a world of her own pleasure.

Mango Goddess is not here to entertain you, but she doesn’t mind you looking at her. She knows she looks good. Her clothing includes an ornate necklace which fills the small space between her breasts and a belt that snakes around her hips and strategically covers her nether regions, a celebration of all things fecund and fertile. She is a sexual being, and owns it as a spiritual power. She is not a victim and she is not a slut. Instead, Mango Goddess represents the might of fertility and beauty, functioning as a proud symbol of abundance in India at the time she was created. If you can think of a Western example of a woman with similar attributes that appears to be equally empowered, please let me know.

Although they are occasionally depicted in Western art, usually labeled as Greek Goddesses or wood nymphs, nude female figures like her are few and far between. Manet’s “Olympia” comes close because she meets your eyes – but the subjects in the painting are both degraded objects, where the artist has deliberately revealed Olympia’s status as a white French prostitute, flanked by a woman of African descent, and done so to be titillating. In this case, the male artist, Manet, used these two female bodies to direct attention to his own genius; they are passive objects in comparison with the artist’s male act of provocation. There is shame associated with her and offense for those with moral fortitude and or taste. In contrast, “Woman beneath a Mango Tree” is intended to be sexy and spiritual; there is no reason for shame.

Vajravarahi, Nepal, 15th Century

Vajravarahi, Nepal, 15th Century

In contrast with the fecund creative women on display, the Arts of Asia show also includes wrathful goddesses, like Vajravarahi, who wears a GARLAND OF SEVERED HEADS ON HER GIRDLE, which happens to be made of bone. Originally installed at a religious shrine, Vajravarahi is typically positioned so that she is dancing on top of a human corpse with a blood-filled skull cap in her left hand, armed with knives and tridents and a staff crowned with skulls. I’m wracking my brain to remember a woman depicted as badass as this in Western art, but I’m coming up short.

Vajravarahi is red, the color of blood and passion. She possesses the lithe body of a yogini and an unrestrained capacity to create and destroy. Vajravarahi also has a pig’s head emerging from the side of her human head, which represents her fierceness. That she has two faces, two sides of her personality, speaks to the binary role she fulfills, with the ability to be compassionate and also merciless in “stripping humankind of ignorance and delusion” through pain and torture. Not only does she reflect the reality of nature as a creative and destructive force, she acknowledges the complexity of women, the power achieved through a combination of fear and adoration.

In Western culture, women are taught to acquiesce, not to be “too” anything, to subjugate ourselves in order to make others more comfortable. Fear of one’s mother is certainly a reality, but female fierceness at a level equal to a man is rarely depicted in art, and when it is, she is a witch, a gorgon, an evil queen, a monster. This fear of judgement, of being “Hillary Clintoned” for reaching for more, is a method of control, with images of female rage seen as ridiculous and inconsequential until the recent landslide of #metoo revelations and collective female demands for retribution and recognition. Recent media exclamations over Rihanna, SZA, Cardi B, and Jhené Aiko, winning at music while defying female stereotypes and owning their power, describe them as “unladylike.” That this term exists at all confirms that our collective consciousness is unable to accept women who are creative geniuses, especially those who refuse to acquiesce to the cliches that keep women in their lane.

In the television show I Love Dick, as well as the book it’s based upon, Chris breaks out of the traditional role she has been assigned as a hand-maiden to brilliant male artists and allows herself to become a “female monster.” She acknowledges her own desires, and that they may make her unattractive to others. Her willingness to share her personal life as art, as well as her unrequited desire for a man, an art career, and intellectual esteem functions more powerfully than the films she had previously attempted to create. Suddenly, Chris is an artist because she is making art infused with a virile personal voice; while the men in her life find her terrifying, or express disappointment in being deprived of the previous comfort provided by her, she is an inspiration to those around her, especially creative women.

Like Chris Kraus, the goddesses on exhibit at The Walters are equally appealing and terrifying, sexy and ugly, creative and destructive, attractive and repulsive all at the same time. They are sirens, hurricanes, lovers, and mothers; most importantly, their power to create or destroy is unfettered. Although they were made in a completely different time with a disparate cultural purpose from mine, I will argue that the images of Indian, Nepalese, and Tibetan goddesses in the exhibition have the ability to reach across time, space, and culture to offer archetypal depictions of female power. They spoke to me directly about myself.

The opportunity to view an empowered creative female representation in all of its complexity, especially within the cultural context of a museum, is a hugely significant to me, especially since Western history has provided so few examples. If you choose, you can view Devi and Vajravarahi as religious historic artifacts and nothing more, but for me, their presence in 2018 in a Baltimore museum within a larger cultural movement feels contemporary and personal. I found inspiration in their ability to embrace a female dynamism that I have rarely viewed in my life, a consciousness only recently awakened in me by an arty feminist television show. Representation matters; the opportunity to expand and embrace my role as a female creator, offered from a different cultural perspective, feels like a giant gust of air, the lifting of a glass ceiling.

Sarasvati, India (10th-11th Century) Sandstone

Sarasvati, India (10th-11th Century) Sandstone

Whether in the form of ancient sculpture, a memoir, or a television series, art serves many purposes. As an artist myself, I choose not to make distinctions between them, viewing them all as a range of human expression. I learn from as much diversity within the arts as possible, and I am grateful for the opportunity to draw conclusions, to see parallels to my own life. In certain scenarios, the art I experience has the ability to shift my consciousness dramatically, to view my environment full of new potential.

I can’t help but wonder what would happen if I lived in a world where female power – both its creative and destructive potential – was widely celebrated, even deified. How would I and other women be different, fiercer, stronger, if we could rely on even buried archetypes of the meanest baddest bitch whore who owns her power? I believe that artists and activists are currently leading us in new directions creating new representations of female power, also digging up maligned versions from the past and resurrecting them. Exhibits like this offer an opportunity to gain strength from and to acknowledge the vast wealth of imagery in Eastern religious art, and to do so respectfully. Creation and destruction are two sides of the same coin and it’s time that women demanded their rightful place, central to this power dynamic.

“I want to stalk you and hunt you like prey / I want to find out where you live / I want to pull up to your house in my Kotex-pink jalopy / I want to open my trunk and show you my cunt-red insides.” – Quote from I Love Dick, Season 1, Episode 3

Arts of Asia, the Walters’ new installation of Asian art in North America offers works from India, Nepal, Tibet, China, Korea, Japan, Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia. The array of 150 works spanning 2,000 years includes more than 30 objects that have never been on view.