Two years after Baltimore’s McKeldin Fountain was demolished, an arts group has brought it back to life with an “augmented reality” app for smartphones and a companion exhibit by Edward Gunts

Demolition is the final stage of a building’s life, or is it?

In Baltimore, artists are showing that buildings can have life after demolition, two years after one prominent structure was torn down.

In the process, they’re making a statement about the importance of public space in cities, at a time when more and more of it is being privatized. It’s all part of an effort to show how demolished buildings and underused spaces can take on new life with the help of “augmented reality” technology and other emerging art forms.

The Baltimore project, called Nonument01 and designed in collaboration with the Museum of Transitory Art (MoTA) in Ljubljana, Slovenia, is the first in a proposed series of international initiatives aimed at bringing attention to public spaces that are lost, threatened or in transition. It touches on a wide range of issues related to the public realm, including freedom of speech, surveillance, stewardship and upkeep

According to the lead artist, Lisa Moren, some of the technology employed by her group has been used in museums, but “this is the first public monument in Baltimore presented in augmented reality.” Her team calls the result ‘Baltimore’s invisible memorial.’

“No one has done anything to this scale,”said Moren. “There were no models. We’re pushing the technology.”

The structure that was given new life is the McKeldin Fountain (1982-2017), a manmade waterfall that helped define a key public space in the heart of Baltimore, where downtown meets the harbor.

Designed by Thomas Todd of Wallace Roberts and Todd in Philadelphia and completed in 1982 as part of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor redevelopment, the fountain was both a utilitarian piece of the city’s infrastructure, with a pedestrian bridge that spanned 6 lanes of traffic and shallow pools that kids could splash in, and a sophisticated work of Brutalist architecture, listed in Baltimore’s inventory of city-owned public art along with nearby works by Kenneth Snelson and Mark di Suvero. The term Brutalism comes from the French “beton brut,” which means raw concrete.

Set on a triangular traffic island at the intersection of Pratt and Light streets, the fountain was designed to be an explorable waterfall formed by a series of concrete prisms, with platforms at different levels containing plants, water and walkways for people. It rose 18 feet, with water cascading down all sides and collecting in pools below. Its colors and materials were consistent with much of the infrastructure around the harbor and many of the beige-toned buildings of the time, which the critic Peter Blake once likened to bars of soap.

Todd’s creation, also called The Waterfall, wasn’t delicate and symmetrical like the Beaux Arts fountains in Baltimore’s Mount Vernon neighborhood, but it had a raw kinetic energy that drew people to it, and it co-existed comfortably with the traffic passing all around. The sound of the water masked the noise of vehicles. It had enough height and mass to “hold the space” at that pivotal location and serve as a backdrop for civic events. It wasn’t a copy of anything anywhere else.

The fountain was named after and dedicated to former Mayor Theodore McKeldin, who inspired the Inner Harbor’s redevelopment with a speech in 1963. The adjacent public plaza, McKeldin Square, was designated a Free Speech Zone, where people could gather for both protests and civic celebrations and even take up temporary residence, as dozens did during the Occupy Baltimore movement of 2011.

A private business group called the Downtown Partnership of Baltimore led an effort to have the publicly-owned fountain demolished, saying it blocked views and presented an unattractive gateway to the central business district. The business leaders cited the fountain’s Brutalist design as a reason to remove it from the landscape. They also made clear they weren’t happy that the area was a gathering point for demonstrators. The same group supported an effort to raze another Brutalist building that stood several blocks away, John Johansen’s 1967 Morris A. Mechanic Theatre, demolished starting in 2014 and now a vacant lot.

City officials allowed the fountain’s demolition after the private group said it would raise funds to replace it with a monument that its members considered more palatable. There was talk of a design competition but one was never held. Demolished between October 2016 and January 2017, the fountain has been replaced by a grassy field, with some seating and trees.

The artist team included Moren, Professor of Visual Art and Graduate Program Director of the Intermedia and Digital Media MFA Program at the University of Maryland Baltimore County; Jaimes Mayhew, a community artist and UMBC alumnus, and two representatives from MoTA,, Neja Tomsic and Martin Bricelj Baraga.

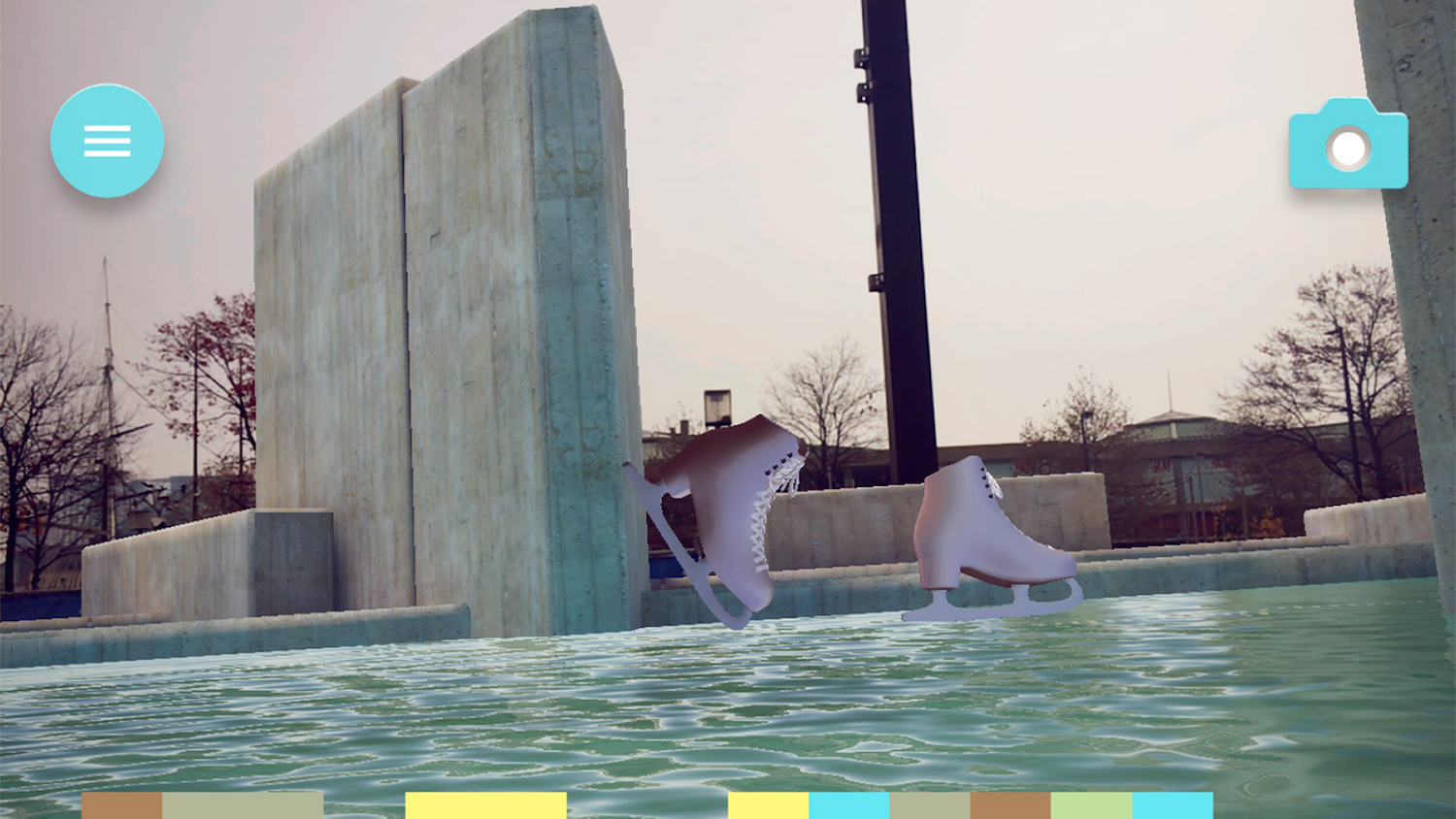

Knowing they couldn’t rebuild the fountain literally, the artists rebuilt it virtually. They created an augmented reality app that people can use to call up images and information about the fountain on their smart phones and iPads. They also mounted a companion art exhibit that tells the story of the fountain and the people who visited.

Augmented reality technology enables digital images to be superimposed on the real world. The Baltimore app, called “Nonument01: The McKeldin Fountain,” is available at no charge from the Apple Store or Google Play and can be downloaded on iPhones, iPads and android phones. (Since videos are streamed in, wifi or data access is required.) As an alternative to streaming, users can collect videos in the game and watch them.

Because the concept is new, the artists prepared a brochure explaining how to experience it. “Nonument01 is an augmented reality app that memorializes the transitory nature of everyday experiences,” they explain in the brochure. “Viewers hold up a tablet or smart phone like a protest sign and bring back a full scale, 3D architecturally correct simulation of the McKeldin Fountain. When the viewer wanders the half acre fountain, they experience a unique multi media world with local heroes reminiscing on the history of its protests, performances and everyday urban experiences.”

Viewers can use the app to see the monument from anywhere they have a working device. For those who are off-site, the app can bring the fountain into their living room or bedroom, but to see the full app viewers need a half acre of flat, unobstructed space. Therefore, the artists say it works best when the viewer is on the former site of the fountain. Besides seeing images of the structure with the city as backdrop, viewers can tap on “memory objects” to view excerpts of interviews with 18 people who interacted with the fountain in different ways, from Occupy protesters to an architect to an ice skater, and learn what it meant to them.

Nonument ( for ‘’no monument’) is an international research project curated by MoTA, addressing memory in public spaces that hold symbolic value for “ordinary people.” According to its organizers, the Nonument movement was started to “identify, map and archive” hidden, abandoned or forgotten public spaces, architecture and monuments. Unlike static works of bronze and stone, the artists say, Nonument makes use of new media forms to convey the transitory nature of urban life. Nonument01: The McKeldin Fountain app is the first project in a proposed series of works, each meant to be site specific

Over the years, preservationists and historians have taken a variety of approaches to keeping alive the memory of demolished structures, from producing scale drawings for the Historic American Buildings Survey to photo documentation to salvaging parts of a building and displaying them or incorporating them into other structures. This is an extension of a long tradition of art historians and preservationists working to preserve historical artifacts” for future generations, using 21st century technology, she said.

One particular focus, she said was “public space and behavior,” the changing ways a space can be used over time depending on who controls it and how surveillance changes public behavior.

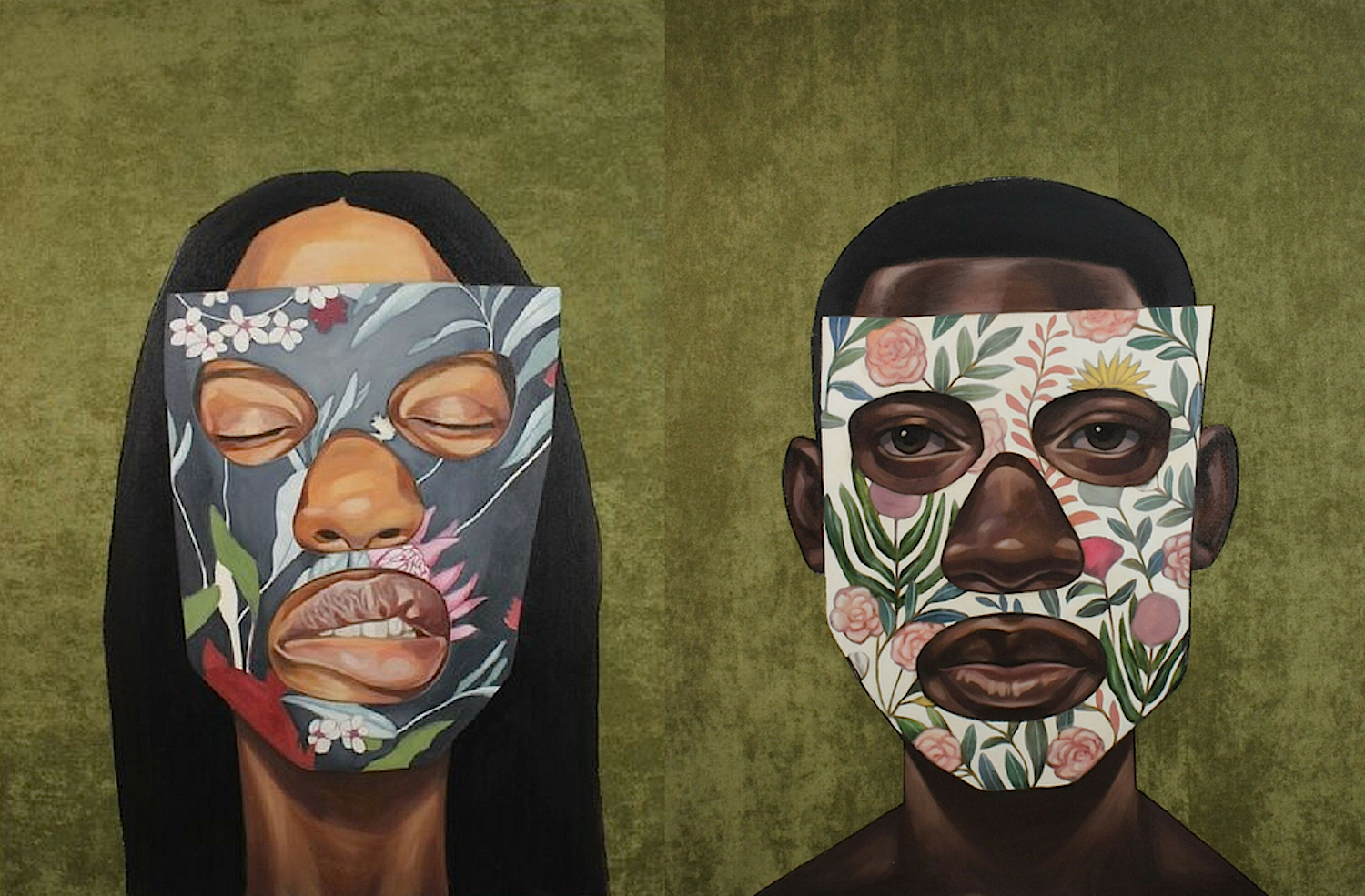

Lisa Moren

Lisa Moren

“We wanted to look at the ways public space is used because of changing policies and private interests, how changing the rules can effect behavior,” she said. “Quasi public space. The escalating privatization of public space. Spaces that are transitory, changes in boundaries, what happens to our freedom in terms of being able to wander and own the streets. The people who make a public space important and vital by their fleeting activities that activate the space.”

It’s also an extension of Moren’s efforts to study and celebrate works of art and architecture that are in various stages of transition. She has spent much of her career researching public spaces that have been lost to the wrecking ball or through wars, and looking for ways to keep their memories alive. Her creative work took her to Eastern Europe, where she created new media works documenting memories of former Socialist republics. While there, she became acquainted with the Museum of Transitory Art.

At MoTA, Baraga and Tomsic wanted to question Socialist monuments in public spaces today through the Nonument project and were looking for specific places where they could test their ideas. Moren was investigating similar issues of loss and transience in Baltimore. She invited Baraga and Tomsic to explore opportunities in Baltimore, which has been called The Monumental City because of its many statues and monuments. They decided to collaborate, calling their joint venture Nonument01.

Moren said she considered several places to focus on but decided the McKeldin Fountain would be the best candidate to bring back to life through augmented reality. “We were looking for a public space that was going through a transition,” she explained. “A place where public interaction would be different after the transition.”

Besides being a prime example of Brutalist architecture, she noted, the fountain was centrally located in the city and was built to honor a public figure who had a key role in sparking the city’s “renaissance.” Because it was next to the Harborplace shopping pavilions, which draw millions of visitors a year, it was well known locally. People from all over the city and from all walks of life have been there. Its role as a designated free speech zone and site of gatherings for both celebrations such as a Super Bowl victory and periods of civil unrest, gave it additional layers of significance. All of this became subject matter for her art.

Moren approached the three year project with a clear point of view: that the fountain was a significant feature of the urban landscape and shouldn’t be lost. A former resident of New Jersey and New York who moved to Baltimore, she said she remembers taking her son to a protest at McKeldin Square in 2015, following the death while in police custody of West Baltimore resident Freddie Gray. But she said she didn’t want her personal feelings about the place to color the way it was remembered.

Moren said she set out to tell two main stories, the architectural story about the physical object as a noteworthy example of Brutalist design, and the human story of the area’s history as a free speech zone and public gathering space for the people who animated the physical object. She envisioned the new monument as the opposite of the stereotypical military-general-on-a-horse statue found elsewhere around town, and she wanted to use the latest advances in digital technology and new media to tell its story. “With new technology, you can create more immersive experiences,” she said.

The app was developed by a local AR/VR studio called Balti-Virtual, and music was composed by Erik Spangler. Funding came from the Saul Zaentz Innovation Fund at the Johns Hopkins University Film and Media Program, the Imagining Research Center at UMBC; the Baltimore Women in Technology micro grant program, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Grit Fund

The accompanying exhibit was on view at Maryland Art Place until the end of May. Moren plans to take it to South Africa, where it will be on display during the 2018 Inter-Society on Electronic Art (ISEA) symposium in Durban, and to a conference about monuments in Prague in 2019. The Museum of Transitory Art, meanwhile, is seeking proposals from artists who would like to create Nonuments in other parts of the world, not necessarily using the same approach taken in Baltimore.

Moren said she’s gratified by the response to Nonument01 and the discussions it has triggered. She said she hopes people will visit and interact with it the way they visit the American Visionary Art Museum, the Polish Monument and other local places where they can see art.

“We set out to make an experience that would claim public space and celebrate the people who used it,” she said. “I hope Baltimoreans will feel like they own this as 21st century monument to everyday people, that this is part of their city now…No other city has a monument like this.”

But she also laments that her effort to “bring back” the fountain was needed in the first place.

While the Nonument project wouldn’t have made as much sense without the threat to the fountain, she said, “I’d rather have the fountain than the project.”

About NONUMENT 01

Breaking from traditional medium of bronze and stone, NONUMENT 01::McKeldin Fountain celebrates the fleeting experiences of everyday heroes through virtual monuments as the first in a series of NONUMENT projects, followed by NONUMENT 02, 03, etc. An international research project curated from the Museum of Transitory Art [MoTA] in Ljubljana, Slovenia, NONUMENT addresses memory in public spaces that are of symbolic value to citizens. It consists of artistic productions and research aimed at defining the role of monuments today and the ways in which societies mark important landmarks in contemporary urban life. The NONUMENT 01 app is funded by the Saul Zaentz Innovation Fellow at Johns Hopkins University Film + Media Program, as well as The Andy Warhol Foundation For The Visual Arts, The Grit Fund [Contemporary Museum], Imaging Research Center and CAHSS at UMBC. For more information on the NONUMENT series, visit nonument.org.

CREDITS: Lisa Moren, Director and Co-Production; Jaimes Mayhew, Co-Production; Martin Bricelj Baraga and Neja Tomšič, NONUMENT founders; along with programming and development team Balti-Virtual. Music by Erik Spangler with “Whisper Chambers” by JMoney fur and “Guided Audio Tour” and “Finale” engineered by Timothy Nohe, interview audio engineering by Lexie Mountain; 3D models by Ben Shaffer and Ryan Zuber, IRC at UMBC.