The artist-activist collective FORCE: Upsetting Rape Culture disrupted a busy road in 2016 with stories from survivors of sexual assault and intimate partner violence. These stories, written and depicted onto squares of the Monument Quilt, took over two blocks of North Avenue. I splintered off from my friends to traverse the maze of quilts, reading as much as I could until I was overwhelmed. Stories of individual experiences with rape and domestic violence, protests against the criminalization of survivors, and messages of solidarity and affirmation were Sharpied, painted, and embroidered onto body-sized, red fabric squares in a variety of manners: slapdash, expressive, painstaking. I took home a calming token from a healing station on the installation’s perimeter. It’s a red, palm-sized sachet, packed with lavender flowers, that reads “not alone.”

“Being not alone is a thing, something practical—not just a word,” says Mora Fernández, who has worked with FORCE since 2014, and has recently joined as the organization’s fifth and newest staff collective member. Fernández runs La Casa Mandarina, a Mexico City nonprofit that advocates for survivors.

FORCE organizers recognize that public displays of the quilt are triggering for survivors. Such public reckoning and emotional upheaval are necessary to the group’s greater mission to disrupt rape culture and foster communal support and solidarity. “In spaces of friction, that’s where you get the most productivity,” says Kalima Young, an artist, professor, and member of FORCE’s leadership team. “Yes, be triggered. It means something’s moving.”

There is no roadmap to healing for survivors or for families and communities collaterally affected by abuse. Healing takes shape differently for everyone, and FORCE intentionally doesn’t prescribe a regimen for it. Since 2010, when Hannah Brancato and Rebecca Nagle founded the collective, FORCE has asserted that the public needs to help carry the weight. “It is a trigger,” Brancato says. “It’s literally survivors’ stories being laid out to be dealt with. With us, it’s not about not triggering people. It’s about holding space where we can process shit together and not expecting that that should only happen privately.”

FORCE Sew-A-Thon, February 2019 (photo by Madison Trotman)

FORCE began working on the Monument Quilt in 2013. The collective has since traveled to dozens of cities around the country, creating quilts with indigenous communities, students, incarcerated survivors, immigrants, and many others. They’ve displayed quilts at universities, museums, borders, reservations, and more. The fiftieth and final display of the Monument Quilt takes place May 31 through June 2 at the National Mall in Washington, DC, featuring 3,000 quilt pieces made by 3,000 survivors and their allies. This installation will stretch out a third of a mile in length, and probably weighs a few tons. Each quilt square tells a different story; stitched together, they spell out “NOT ALONE” and “NO ESTÁS SOLX.”

The collective has always aspired to display the entire Monument Quilt on the National Mall—a symbolic landmark of our ugly origins, rooted in rape, genocide, trafficking, slavery, and theft. That the Washington display takes place while the United States is led by an alleged rapist-president who keeps a strategic stranglehold on white supremacy by embodying all of the above makes the quilt’s message even more painfully necessary.

The current mainstream uproar against sexual violence has aided FORCE’s mission, but the organization has consistently pushed the conversation when there’s no national spotlight on it. It seems every few years there’s another wave of internet rallying around sexual violence, when people hashtag-share their traumas believing change will come. When I opened Facebook one morning in October 2017 and saw so many #MeToo posts, I immediately felt exhausted, expecting it to have the same short lifespan that #YesAllWomen and #WhyWomenDontReport and others had. But #MeToo helped push conversations about sexual assault and harassment into a more public realm. It’s made people rethink their own pasts, questioning what they’d previously put up with. It’s also emphasized the power of small-scale activism, particularly that of Tarana Burke, whose Me Too movement had been advocating for survivors of color for more than a decade.

“When the project started, there weren’t as many public platforms for conversations about sexual and intimate partner violence,” Brancato says. “I’m not saying that [progress] is linear, because I always feel like we could backslide at any time, but we are in a moment of heightened visibility now.”

Through its actions, FORCE has tried to show how rape culture is complex and structurally embedded into society, how rape is neither a private issue nor a singular one, and how it implicates and affects every person and every community. And it has been collaboration-minded from the start. In the last few years, it has built a more formal organization, with a nationally dispersed leadership team. A Baltimore-based staff of five does the day-to-day work of community organizing, studio managing, strategic planning, youth coordinating, and creative directing. The team collectively decides how to spend money and share responsibilities of creative, administrative, and organizing labor.

FORCE staff collective: Mora Fernández, Hannah Brancato, Charnell Covert, E Cadoux, Shanti Flagg (photo by Joe Hyde)

The collaborative authorship is especially true in the thousands of people—including hundreds of volunteers and interns who’ve sewn and documented it—who created the Monument Quilt over the course of six years. The date for the culminating National Mall display kept getting pushed out, from 2017 to 2018 to this year, largely because building out the organization’s framework, maintaining the values it promotes in the process, took precedence. “FORCE encourages people to think about their personal responsibility, how to harness their own personal power to change the culture, which means changing how you interact with other people and changing how you interact with yourself,” says Shanti Flagg, FORCE’s studio director and collective member.

At the National Mall display, there will be “intentional spaces” all around, offering distinct spaces for visitors in need of healing, grounding, spiritual connection, and communion with folks of similar identity groups. “I think this project forces you to really try hard to see your humanity and everybody else’s humanity all the time,” Young says. “That’s a part of art making. It’s designed to help you see around corners. For me, I think sitting in the muckety muck is my work, my ministry. It’s a place where it’s uncomfortable, but I feel comfortable.”

One of the Monument Quilt’s major arguments is that because there is no singular, definitive experience of sexual assault or domestic violence, there’s power in sharing individual experiences. Norwood Johnson, a FORCE board member and leadership team member, contributed a quilt with other male survivors who met through the House of Ruth. “We’re brought up to be tough and not share our stories,” Johnson says, noting that male survivors often stay quiet. “A lot of us are coming out now.”

Bringing attention to excluded narratives is one way of resisting a single narrative. FORCE’s 2016 “Dollar Genocide” campaign raised awareness about a court case involving a 13-year-old Native American survivor and their family, who sued Dollar General and a store manager who sexually abused the child. The retail chain argued that tribal courts were inferior to American courts and that the suit should be dropped. The case was sent up to the US Supreme Court, which came to a split decision, resulting in favor of the Choctaw tribe. This case was a “really important example of the way that justice for survivors is connected to other systemic oppression and racism,” Brancato says.

The justice system also routinely incarcerates survivors acting in self-defense, especially Black women. In 2012, Marissa Alexander, a Black Florida woman, was prosecuted and sentenced to a mandatory minimum of 20 years for simply firing a warning shot near her estranged husband after he threatened to kill her. In 2015, FORCE joined a coalition of organizers to display the Monument Quilt at the Duval County Courthouse to show support and solidarity with Alexander. Through an appeal and a new trial, Alexander was granted a plea deal which reduced her sentence. Now free, Alexander will be the keynote speaker at the Washington display on June 1, during the Survivor Policy Convening to discuss policy solutions to intimate partner violence that don’t rely on carceral measures.

FORCE Sew-A-Thon, February 2019 (photo by Madison Trotman)

Since FORCE’s beginnings, Baltimore has witnessed a range of abuses, interpersonally and institutionally, either shouted about or kept at a whisper. These acts of violence have occurred in universities, bars, Patterson Park apartments, west-side public housing, dirty warehouse showspaces, theaters, social justice-oriented nonprofits, the police department, online. Sometimes these stories leak into public discussion, and people react with doubt or support, trying to figure out what accountability looks like, often eventually dropping it, unresolved, and moving on. I’ve written essays, poems, and investigative pieces on several of these instances, and each time I start to write another, I want to bang my head against a wall, depleted by the people and organizations ignoring abuse allegations or claiming to have done a transformative justice process without any understanding about what that process is. The persistent lack of support is what makes survivors keep trauma tamped down in the private realm, though it occasionally ekes out and frustrates our relationships with friends, family, lovers. Everyone.

This abysmal circle is why the intervention of the Monument Quilt has been instrumental, though the pace of change is glacial. Once the Quilt wraps up, the FORCE team will assess how to sustain their work in different ways and deepen relationships with Baltimore communities and organizations. Staff member Charnell Covert is working on outreach with local organizations, particularly those whose work is not directly connected to sexual assault and intimate partner violence, “but making the connection between those, and articulating that issues of survivorship are everyone’s issue,” she says.

Crucially, FORCE has started working more closely with young people through Youth Voices for Consent, an offshoot started by staff member E Cadoux. Currently, four teenage artist-activists get paid to lead the program; they’ll host an adult-free, youth-only summit May 31 on the National Mall, with the intention of developing a “manifesto of what consent culture looks like for them,” Cadoux says. Child sexual abuse is often sidelined in larger conversations about rape culture, and the Youth Voices ideas will be presented at the Survivor Policy Convening the next day.

Art will continue to lead FORCE’s advocacy for cultural shifts in support for survivors. Lorena Kourousias, a leadership team member who works with Latinx survivors in New York, has found the Monument Quilt to be transformative for her clients, some of whom have a difficult time putting their experience into words, she says. It’s different when painting, collaging, or embroidering it.

This art intervention is one way to reassert agency and interrupt the cycle of trauma. “It’s not just going and painting, but painting with this intentionality of healing yourself and your community,” Kourousias says. “And knowing that by healing yourself you are also healing your community.”

The final display of the Monument Quilt takes place on the National Mall in Washington, DC, May 31–June 2. For more information on the weekend’s programming, or for information on volunteering, visit the Monument Quilt website.

Featured photo courtesy of FORCE.

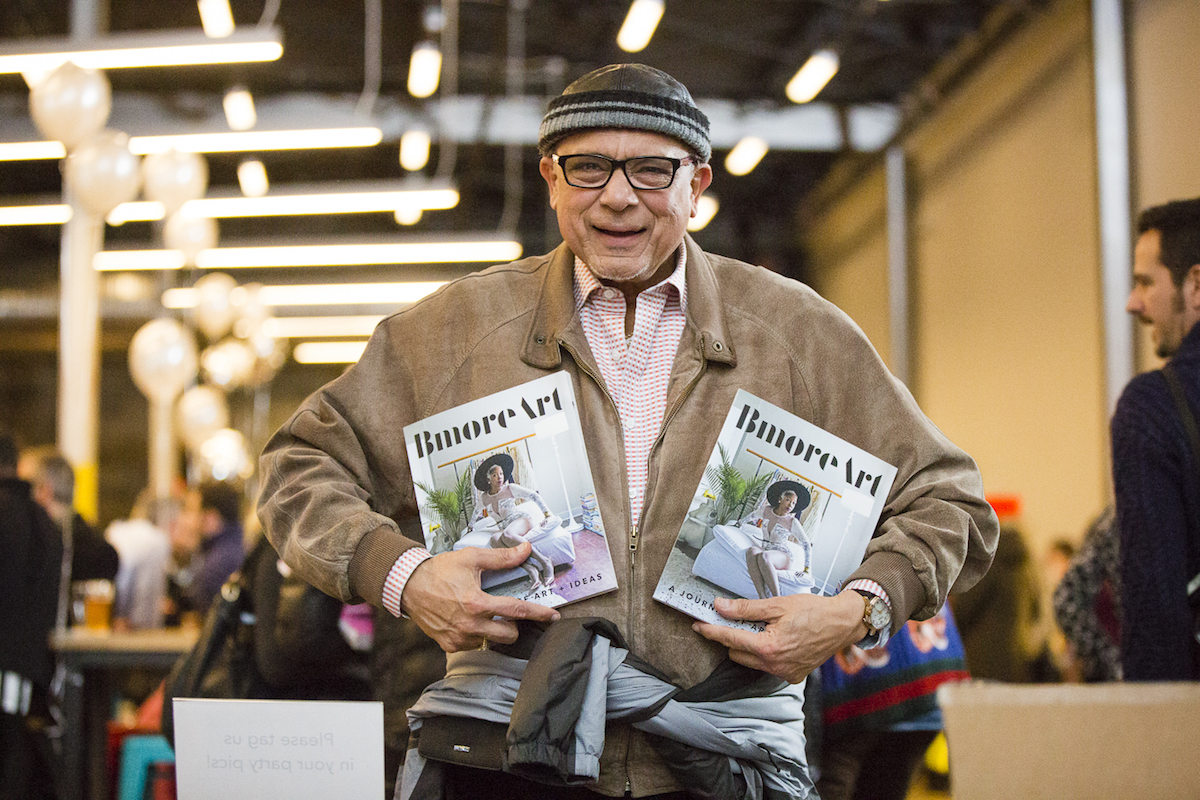

Editor’s note: This story appears in BmoreArt Issue 07: Body. Come to our release party Thursday, May 23, at the Parkway Theatre to pick up your copy of the new issue.