When Sharayna Christmas says the word “dance,” body and movement are in the backseat, discipline of the mind is riding passenger, and spirituality is behind the wheel. Dance is a roadmap to become one with the raison d’être of the Black body, which she believes is the ancestors who live within it. In 2004, she started Rayn Fall Dance Studio, a ballet school for Black children in Baltimore, but for her it was never about just being a classically trained dancer. “I’m responsible for my people,” she says. “Dance is about how the body protects, communicates, and moves about, how it reacts to certain things.”

Black bodies that were once sold for crates of gunpowder and rum, bodies that America has always tried to reduce to things instead of people—how does one turn those Black bodies into temples, shaping Black youth with high quality arts education?

Sharayna’s upbringing and journey address these issues head-on. Before it was a trend to care about Black bodies and the spaces that they occupy, the Harlem native was raised in a family where Black progression was at the forefront. Her mother was an Afrocentric community activist and member of the National Rainbow Coalition, the political organization founded by Jesse Jackson in 1984. She was an influential role model for her daughter, although at 10 years old, Sharayna disliked being at marches, meetings, and organizations, because she was too young to understand the importance of the work her mother was doing.

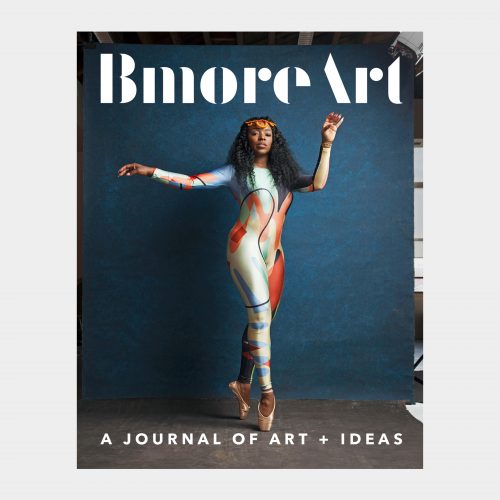

Sharayna Christmas photographed by Kelvin Bulluck, Cover Photo for Issue 07: Body

Sharayna Christmas photographed by Kelvin Bulluck, Cover Photo for Issue 07: Body

In America, your zip code determines a lot: whether your schools look and operate like prisons, whether you get terrorized by police walking through food deserts to purchase everything GMO- and cancer-containing, whether you die at an early age to gun violence, whether you have to fight for just “enough.” There is no such thing as moral absolutism for the oppressed because we don’t play by the same rules as those who were born with “plenty”—a term associated with a paradise-only state. The rules that we have to break in half in order to survive in America will almost always reckon with the moral code of the plenty-holders. But Sharayna has no shame in telling us about the double-edged sword the Black body has to tote in order to survive in America, while teaching your family its true history.

At a young age, she witnessed the systematic ways that Black people were being mistreated. “My past is not squeaky clean,” she says. “If you have family ‘like that’ there’s things you experience, that you’ll be around that you can’t help.” Sharayna grew up in a church, but she had close family members who lived life in the streets, which led to incarceration. It was through personal accounts of incarcerated family members and trips to the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture where she was educated about everything from the Haitian Revolution to literary giants such as Langston Hughes, whose work portrays the joy and suffering of black people during the early 1900s. The duality of her family awakened her revolutionary spirit.

“There were a lot of breakdowns… toxic things that happened, that were my reason for coming to Baltimore,” she says. “Although I came here for school, I wanted to build a livelihood that was outside of that. I came here and started to do the same things my mother did: working with young people. Loving Black people and helping them to love themselves.” Sharayna received her BA in finance from Morgan State University in 2002 and went back to New York for a job at Goldman Sachs, but she returned to Baltimore in 2003 to teach Black youth ballet at the Druid Hill Park YMCA.

Wanting to provide Baltimore youth with opportunities to develop as leaders, Sharayna expanded Rayn Fall Dance Studio to create new programs under the umbrella of her nonprofit, Muse 360 Arts. The Spark of Genius: Youth Entrepreneur Project offers workshops and conferences to engage with community leaders and business owners, and New Generation Scholars offers classes on African diasporic history and culture, with opportunities for travel to enhance the students’ education on the diaspora. The group has travelled to New Orleans and New York, and taken international trips to Cuba, Jamaica, Costa Rica, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, the Bahamas, London, and Paris. They took their tenth trip, in July of this year, to Ghana.

Sharayna cites several major influences, performers and artists who understood the value of being Black, that inspired her to build a variety of programming initiatives in Baltimore. There’s Dr. Marimba Ani, a Pan-Afrikanist, researcher, and anthropologist who speaks of the history that lives within black people through time and how that spirit manifests through purpose. And Arthur Mitchell, founder of Dance Theatre of Harlem, where she started her training at the age of three, who used Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s death as fuel to create a ballet school in the basement of the church, as the inspiration for her own creation of spaces for Black youth. “He knew that opening the school wasn’t about him or ballet, so he is the person who influenced me the most,” she explains. Alvin Ailey, the choreographer, activist, and founder of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, “saw the beauty in Black people and used dance to show us the way that they lived in the rural South,” Sharayna says. Dr. Pearl Primus, the dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist, resonates as well, in her mission to uplift the reputation of African dance to American audiences.

Growing up in Baltimore, my friends and I knew that we had talent; we knew that we were different than the norm, but we didn’t have any outlets to claim the gifts we possessed. Hip-hop was the most influential genre of music in my life, but the rest of world called it “devil music,” and blamed it for the violence in my community. My friends and I loved to paint on our tennis shoes and alter our shirts, caps, and jeans with scissors, needles, and thread. The rest of the world said it was the way “thugs,” “hoodlums,” and “ghetto” people dressed, dehumanizing and criminalizing our culture, while we saw it as style. With music and fashion being the two forms of art that I loved most growing up, I still always viewed them as “less than.” We would have died for someone like Sharayna to see the genius in us, and channel it through education and travel outside of Baltimore.

For Sharayna, it’s not enough to simply educate Baltimore youth; she wants to inspire them completely to view their social context from a new perspective, both to recognize the value in their own lives and to realize there is a much larger world beyond where they were raised. “Traveling outside of the United States is spiritual for me,” she explains. “When I take the young kids out of the country it refills them. They become better artists, curators, writers, and so on.” After the immersive travel experiences, full of performances and museum visits that further their studies of the African diaspora, her students are more prepared to set long-term goals for the future and make an impact with their work back in Baltimore.

“I feel like Baltimore really raised me, in a sense, to be the woman that I am,” Sharayna says. “I would never be like this in New York. I might’ve been an activist, but I wouldn’t have a dance school, or I wouldn’t be mentoring youth. I wouldn’t have as much of a presence and impact. Baltimore forces you to make shit happen. Black bodies in Baltimore are the epicenter of Black progression.”

After a decade of working in the Baltimore cultural arts community, she decided to create a new platform for underrepresented artists of color, featuring their work through exhibitions and collaborations called Necessary Tomorrows. “The purpose of this initiative is to represent those of us who stand outside the circle of society’s definition of what’s acceptable and works to design a future with us in mind,” she explains. Last year, Necessary Tomorrows worked with with 23 artists, sold over $13,000 worth of artwork, produced ten shows, hosted seven studio visits, and created four new artist collaborations exhibited in a variety of community spaces. Later this year she will launch the Necessary Tomorrows Fund to implement small grants support the work of Black creatives (and creatives of color) in Baltimore.

Sharayna believes that when Baltimore improves culturally, economically, and socially, the lives of all city residents will get better. For her, Baltimore is a barometer for cultural progress: The quality of life for Black people in Baltimore is a direct reflection of America’s truth. She sees herself as part of the city’s slow progression. “Baltimore has some of the most creative individuals I have ever met in my life,” she says. “But Black bodies in Baltimore are suffering because the system is not serving the people. They are not done using Baltimore as a poverty story.”

She is realistic about the challenges ahead, but her passion drives her to keep moving forward, to offer opportunities for empowerment for Black people in Baltimore.

“Even though I have accomplished a lot, I’ve got a lot of healing to do,” she admits. “I’m responsible to my people. Now what does that cost me? It costs me a lot: mentally, spiritually, physically. If I had it my way, right now, I’d rather be somewhere in somebody’s village, with somebody’s grandmother, giving me the space to just experience the sun. Because of all the work that we do, sometimes we just need a second to heal and refuel ourselves. And I feel like that can only happen on the continent, Africa.”

This article was originally published in the BmoreArt Journal of Art + Ideas: Issue 07 Body.

Photos by Kelvin Bulluck.